TWO UNFORGETTABLE SITES IN PUGLIA

Not to be missed on a visit to Puglia is a 13th century citadel, the magnificent Castel del Monte, about 70kms north of Matera. Strategically perched on a hilltop in the Murgia region at an altitude of 540m that can be seen from many kms away, it seems to dominate the entire Kingdom of Sicily, of which Puglia was a part at that time. Another site, that’s one of the country’s most historically important, is Cannae. Anyone who has ever heard of Hannibal will doubtless know that his Carthaginian forces defeated the Roman army on numerous occasions, and the battle at Cannae in 216 BCE during the Second Punic War, was the most significant of these. It’s regarded as one the bloodiest battles in Roman history—definitely something for those of us with an interest in ancient history.

One of the most famous cultural sites of Puglia, its architecture and history are the strengths of the magical Swabian Castel del Monte. It was built around 1240 by Frederick II following his first visit to the region in 1221. He fell in love with this rich region, its culture, and especially the numerous rivers and forests where he was able to indulge his great passion: hunting. Just two years after his visit, the capital of the Kingdom of Sicily was moved from Palermo to Foggia, which is in the centre of the Puglia Tableland. By this time, Frederick was King of Sicily, King of Jerusalem, King of the Romans, King of Italy, and Holy Roman Emperor. A busy man indeed!

Castel del Monte is a part of a castle system that was a distinctive and highly visible statement of the Sovereign’s power and magnificence. These castles and palaces combined many purposes: residential, administrative, and of course, defensive. Due to its octagonal shape and location, experts think that Castel del Monte probably wasn’t built purely for military purposes, and also given that it has no moat or drawbridge, no arrow slits, and no trapdoors for pouring boiling oil down onto invaders! Rather, Castel del Monte is an expression of Frederick II’s love for art and architecture.

Certainly, the shape is the most iconic characteristic of Castel del Monte. It’s based on an octagon, with an octagonal tower placed on each of the eight sides of the castle. The number eight recurs even in the number of rooms for each floor, and each of the 16 rooms has a trapezoidal shape. The calcareous stone and faceted shape of the towers generate many colours and light effects during the day. Frederick imbued the castle with symbolic significance—as reflected in the location—the mathematical and astronomical precision of the layout and its perfect, regular shape.

Inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1996, UNESCO describes Castel del Monte as a blend of elements from classical antiquity, the Muslim world and north European Cistercian Gothic, which reflected the broad education and cultural vision of its founder, Emperor Frederick II. His cosmopolitan outlook was illustrated by the fact that he brought together Greek, Arab, Italian and Jewish scholars to his court in Palermo, which designates him as one of the precursors of the modern humanists.

The integrity of the castle has been protected, in part, due to the fact that it has not undergone any significant structural alteration. Any conservation work has been of good quality and consistent with the best Italian standards. Its setting has remained unchanged as it still sits, in isolation, on a rocky peak dominating the surrounding landscape. However, some of the marble and mosaic interior decorative elements have deteriorated over time and have had to be either replaced or removed entirely.

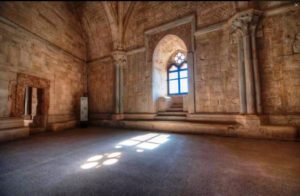

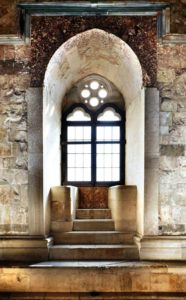

Visitors can visit the castle’s two floors. Due to years of abandonment, the interior is relatively bare since most of the furnishings and decorative objects were removed. Much of the original splendour, such as the marble that once covered the walls, has now disappeared, but traces appear here and there.

Its interconnecting rooms have decorative marble columns and fireplaces, and the doorways and windows are framed in corallite stone. Many of the towers have washing rooms with what are thought to be Europe’s first flushing toilets—Frederick II, like the Arab world he admired, set great store by cleanliness. After Frederick’s death, the castle was used as a prison, before it eventually slid quietly into disuse.

This beautiful castle is regarded with great admiration in Italy and has been chosen as an image for the one cent Euro coin minted in Italy, as well as for various stamps and symbols, for example, on the flag of the Puglia region.

It’s also a great location for special events: Castel del Monte was the venue for the House of Gucci’s parade of its womenswear collection in May 2022.

Because of its relative isolation, getting to Castel del Monte is something of a challenge without a car. There are buses though that run from the town of Andria, about 20kms to the north, which can be reached by train from either Bari or Trani. Castel del Monte is open every day.

About 30 kms north of Castel del Monte lies the long-deserted town of Cannae, situated on a small hill known as the Monte di Canne, and strategically located around 10 kms inland beside the Ofanto river, known in Roman times as the river Aufidus.

Only a village during the Roman Republic, it later expanded and grew to the status of town or municipium by the time of the Empire. From its position on top of a hill, Cannae commands a dominating position across the plain of Ofanto, offering a panoramic view that extends to the distant hills of the Gargano peninsula. This location, with its fertile, flat valley, natural water supply and an unsurpassed defensive position, made it a natural choice for human settlement.

In the environs of Cannae, archeologists have found Neolithic and Bronze Age sherds, a menhir and Iron Age and archaic Apulian burials in which were found 6th-5th century BCE geometric-ware grave goods.

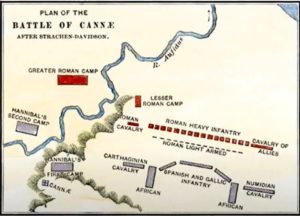

After years of conflict, known as the Punic Wars, between Carthage and Rome, Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps from Gaul (France) sent shockwaves through the Italian peninsula that grew with intensity the further south he headed. Everywhere he went, he triumphed, despite Rome’s sense of superiority and belief that they would ultimately defeat the invader. However, each of Hannibal’s victories were bigger and more glorious than the last, until the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE, when the Romans were dealt such a severe blow that it threatened to change the balance of power and the course of Mediterranean history forever.

The two joint Roman Consuls, Varro and Paullus, who had been sent out by the Roman Senate to finally defeat Hannibal, could not agree on tactics, and neither could overrule the other. The supreme command of the army alternated between the two Consuls on a daily basis, and it was on Varro’s watch that the massive Roman army lined up against the cunning Hannibal and his forces. Although no definite number of Roman troops exist, the ancient sources say that the Romans had over eight legions and an estimated 2,400 cavalry–the largest army in the history of the Roman Republic. All sources agree that the Carthaginians faced a considerably larger foe than their own numbers.

Hannibal’s army was made up of many different nationalities, including Spanish and Gallic soldiers. The Romans’ sense of their own superiority totally underestimated the way Hannibal had united and trained his disparate force. Hannibal placed his weakest troops in the centre, luring the Roman army into a trap, whereby the Numidian cavalry and battle-hardened Libyan soldiers executed a classic pincer movement and annihilated the enemy.

The result was at least 50,000 Roman and allied troops killed, while Hannibal lost around 6,000 men. Only about 15,000 Romans, most of whom were from the garrisons of the camps and had not taken part in the battle, escaped death. Paullus, who had opposed his colleague’s battle strategy, remained on the battlefield to die with his men rather than face the ignominy of surviving such a disaster. Varro had no such qualms, and fled back to Rome.

By inflicting such a humiliating defeat on the mighty Roman Empire, Hannibal proved himself to be one of the greatest ever military strategists. It remains a subject of much speculation as to why Hannibal didn’t march on a weakened Rome and take the capital, but instead, he sent a delegation to Rome to negotiate a peace treaty with the Senate on moderate terms. Some say that Hannibal’s aim was not to flatten Rome, but rather, it was to be left with a role, but without a confederacy. Despite the multiple catastrophes Rome had suffered, the Senate refused to contemplate any such thing. Rome continued to fight numerous, albeit smaller, battles against Hannibal, with a strategy of steadily reducing Hannibal’s forces. Eventually, due to the shortage of manpower, Hannibal had no option but to take ship with his army, back to Carthage.

At the Archaeological Park, the visit starts with the Antiquarium di Cannae Museum and information centre before ascending the hill of the battle site. The museum is set out in chronological sections, that details the site from remains of the ancient Daunian settlement of pre-history, fragments of the Bronze Age inhabitants, plus Roman, early Christian and medieval remains, and of course, the Battle of Cannae between the Roman army and Hannibal’s forces.

The museum offers visitors a rich and fascinating visit, with lively graphics and quality multimedia elements, with particular emphasis on the historical battle of the second Punic War. The story of the battle is told in a video reconstruction in 3D in a multimedia room, and also via historical sources in interactive multimedia units, featuring tactical manoeuvres and protagonists. The museum’s large windows establish a connection between the archaeological artefacts, the natural scenery outside and the ancient citadel.

The site itself has a strata of the remains of buildings and monuments, with megalithic caves and graves, portions of ancient walls and a large stone menhir linked by legend to the classical hero Diomedes. Later, in Roman times, enormous estates worked by slaves produced vast quantities of grain from the area. The wealth produced enabled the funding and construction of a fortress and grain stores, which were vital in feeding the population of Rome.

A road leading up to the town was once lined with houses and workshops–some fragments of whose stone walls remain today–still exhibit remnants of Roman mosaics, along with the vestiges of shrines and pillars that mark out the ancient Agora. The public Forum lost most of its stone to the later construction of the medieval walls and the castle of Cannae, its Basilica and crypt.

You can also see huge “cyclopic” stone blocks dating from the 5th century BCE, and the Aragonese castle walls from the Middle Ages, and Christian basilicas. In 1083 the town was conquered and partially destroyed by Robert Guiscard, and in 1303 Charles II of Anjou annexed the entire territory of Cannae to that of Barletta. At the end of the Middle Ages, the site was gradually abandoned.

The summit of the hill offers an excellent view of the battlefield below. Gazing out across the tranquil countryside stretched out below, it’s hard to imagine that it was the site of one of history’s most famous battles. At the far north-western corner of the hilltop, overlooking the Ofanto River plain, there is a marble column with an inscription in Latin from Livy Book XXII.54, that sums up the significance of the site: “No other nation in the world could have suffered so tremendous a series of disasters and not been overwhelmed.”

[email protected]

Cara Cheryl, Most interesting article on Castel del Monte and Cannae. Loved history of Carthaginians and Hannibal. Rxx

Cheryl Brooks

Buongiorno cara Robbie,

Delighted that you enjoyed the story. Both most interesting destinations, which are indicative of the huge breadth of history in the region of Puglia. We thoroughly enjoyed exploring it, and every day offered fascinating insights into the whole area. Never a dull moment!

Cheers, Cheryl