MATERA – SOUTHERN ITALY’S MOST EXTRAORDINARY SITE

Italy’s southernmost region has many great sights and attractions, including huge fortress palaces, white-washed towns and villages, the extraordinary trullis that are only found in the Valle d’Itria, and some stunning beaches. As well as these treasures, there is one spectacular place that no visitor should miss. Matera is one of the most extraordinary destinations in Italy. This remarkable city, the third oldest continuously inhabited in the world, that once held so much sorrow for so many of its inhabitants, is perhaps one of the most fascinating you will ever visit.

Strictly speaking, Matera is not in Puglia, but actually lies in the adjacent region of Basilicata on the border with Puglia. However, it’s fair to say that most people, when they think of Matera, tend to include it in the general region of Puglia. 65kms south of Bari, Matera lies on the right bank of the Gravina river, whose canyon forms a boundary between the hill country of Basilicata and the Murgia plateau of Puglia.

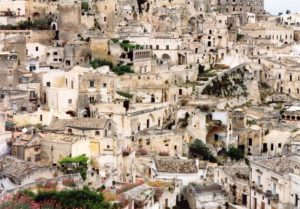

Matera began as a complex of cave dwellings, first occupied in the Paleolithic Age, that were excavated into the soft limestone of the steep western side of the gorge. Two streams flow into the ravine leaving a narrow, defensible promontory in between them. The central high ground, or acropolis, eventually became the site for the cathedral and administration buildings, and this area became known as the Civita, and the settlement that scaled down the cliff and burrowed into the sheer rock face, became the area known as the Sassi.

The Sassi is made up of around 12 levels, rising up the steep topography to a height of 380m, connected by a network of paths, stairways and courtyards. The medieval city above, on its plateau on the edge of the canyon, cannot be seen from the western approach. The Civita and the Sassi, are relatively isolated from each other. This situation remained in place for hundreds of years, and survived the expansion of public life outside the main Piazza Sedile out onto the open plain (the Piano) to the west, and this shift was followed by the elite residences in this direction from the 17th century. By the end of the 18th century, this physical separation had developed into a class boundary, and the two communities no longer interacted socially.

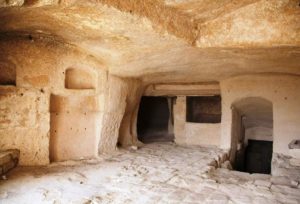

By the mid 20th century, the Sassi was declared unfit for modern habitation. Conditions had become atrocious, there was no electricity, running water or sewerage system, no natural light or ventilation. Families were cramped together with their animals, diseases and poor health issues were rife, while infant mortality was an appalling 50%. It became known as “la vergona d’Italia” (Italy’s shame). The government forced the inhabitants of the Sassi to re-locate, which caused tremendous uproar and social breakdown. Nevertheless, about 16,000 of the Sassi population were forcibly moved to new accommodation in the modern part of Matera.

The abandonment of the Sassi inevitably led to further degradation, but there were always those who were keen that the history of the Sassi and its inhabitants didn’t fade away with the passing years. A group of about 2 dozen Materan students, who had grown up in the more modern, affluent world of the modern city, decided to rebel against their city’s notoriety. They formed a cultural club to salvage Matera’s past, called the Circolo la Scaletta—the Circle of Stairs. They were young men and women, medical students, law students, housewives, but not a single trained archaeologist among them. They began exploring the desolate Sassi, which by then had become overgrown and dangerous.

They found abandoned archaeological treasures, including centuries-old rock churches that had been created by Byzantine monks, decorated with beautiful frescoes, and evidence of ancient occupation dating back to the Neolithic period and earlier. In 1966, La Scaletta published its own book on the cave churches. Gradually, after much lobbying, Government grants allowed for repair and restoration work to begin in earnest. One of the most pressing needs was for the stabilisation of the labyrinth of cave dwellings especially the roofs, many of which were found to be the foundations for the next level above.

When you see these dwellings, it’s hard to imagine that some of the holes in the rocks were once entrances to a home. What had started out as a prehistoric troglodyte settlement, and believed to be among the first human settlements in Italy, had been continuously inhabited until the mid 20th century. In 1993 the Sassi was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site as ‘the most outstanding, intact example of a troglodyte settlement in the Mediterranean region, perfectly adapted to its terrain and ecosystem.’

There are around 1,500 cave dwellings that honeycomb the steep ravine, and today, a number of them are open as museums. The cave dwelling of Vico Solitario is a museum within one of the caves. It displays artisan tools and furniture typical of the period and provides an interesting insight into the way of life for the residents within these dark, cramped caves. In a typical cave-dwelling, a family, with an average of six children, lived with their animals. In a small alcove of the cave would be the animal stall, which often contained a mule, pigs, chickens and other farm animals. There were no toilet facilities, only a ‘cantero’, a terracotta pot with a wooden lid kept by the bed.

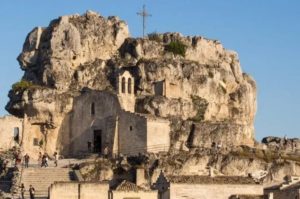

The spectacular Chiesa di Santa Lucia alle Malve is carved into the rock and takes pride of place above the Sassi dwellings of Matera. The church dates to the 15th century and has a small bell tower.

On the next level down is the church of San Pietro Caveoso. This church also known as the Chiesa di San Pietro e Paolo, was originally built in 1218, but has undergone numerous refurbishments since then. Of the various so-called rock churches, Santa Lucia alle Malve is considered to be the most important in the history of Matera.

It was the first female monastic settlement of the Benedictine order dating back to the 8th century. It’s a church of considerable size whose exterior front is along the rocky wall with a series of entrances giving entry to many internal cavities.

The modern repurposing of the Sassi’s historic interiors has been endlessly inventive. Along with cave hotels, there are cave restaurants, cave cafes, cave galleries and cave clubs. There is an underground swimming pool, evoking an ancient Roman thermae, with lights creating hypnotic water patterns on the ceiling, and a contemporary art museum, MUSMA, with its own underground network, highlighting—unsurprisingly—sculpture. One cave complex is now occupied by a computer software company with around 50 employees.

The modern, Civita, part of Matera often fails to rate a mention in most guides to the town, which somewhat understandably, tend to concentrate on the Sassi. However, the town itself is well worth exploring. The origin of the name comes from the Latin civitas (city), and in fact is the oldest part of the town. Enclosed within the walls until the 16th century, it was something of a natural fortress, clinging to a pyramid-shaped plateau surrounded by the Gravina ravine and steep cliffs.

There is a very fine 13th century Romanesque Cathedral, built right on the uppermost part of the town, indicative of its importance. It once had medieval fortifications, and today, there are the remains of the numerous towers that surrounded it, as well as some of the most beautiful buildings in the city, including the Firrao-Giudicepietro palace.

The town has plenty of very pleasant outdoor cafes and restaurants to satisfy any taste and budget. Don’t miss the wonderful local cuisine, with its delicious oven-baked breads, mouth-watering cheeses, and a huge variety of home-made pasta best accompanied by a bottle of two of Matera’s local DOC wines. The town has some good accommodation choices. Palazzo Viceconte is right on the edge of the steep cliffside of the Sassi and offers spectacular views from its rooftop cafe and terrace. As a greast bonus, it also has parking available. Not far from this hotel the 5-star Palazzo Gattini is also very well located.

Under the main plaza in the modern town, visitors to Matera can follow metal walkways through an enormous 16th century cistern complex with chambers over 15m deep and around 73m long, which were discovered in 1991 and explored by scuba divers.

It’s easy to see why Matera, especially the Sassi area, has been chosen to double for ancient Jerusalem in films, including Pasolini’s ‘The Gospel According to St Matthew’ and Mel Gibson’s ‘The Passion of the Christ.’ More recently, a key part of the James Bond film, ‘No Time To Die’ was filmed in Matera, mostly around the Sassi area, and since then tourism has increased considerably. In 2019, Matera was declared a European Capital of Culture, in acknowledgement of its unique place in European history and culture.

Driving towards Matera, especially from the south east, is across gently rolling countryside, providing no hint of the deeply eroded gorge that gives Matera its stunning composition. The only way to really discover Matera is on foot, so comfortable, thick-soled footwear is essential. A walk along the main road offers some wonderful viewing points along the way. The main two viewing points are Belevedere Piazzetta Pascoli and Belvedere Luigi Gurrigghio, which provide stunning views of the Sassi. At least an overnight stay is essential to exploring Matera, and the panorama at night overlooking the Sassi from the height of the new town is a jaw-dropping, almost otherworldly experience. I can guarantee that you will never have seen anywhere quite like it!

Once again a fascinating read thanks Cheryl for your wonderful research.

Hi Sandy,

Thank you so much for your lovely message, and I’m so delighted you enjoy the stories. You are exactly the sort of reader I write them for!

Kind regards, Cheryl