CASTLES AND FORTRESSES OF PUGLIA

Puglia is a land of conquests and domination. Strongholds and castles stud the countryside throughout the region, majestic symbols of ancient nobility, but also a turbulent past. The castles were not built purely as residences, but rather as heavily-fortified bastions that could stand strong and invincible against all comers, whether by land or by sea. There are no mountain peaks for Puglia’s castle strongholds. Instead, its horizon traces, almost without interruption, a flat line lacking any elevations. There are around 49 great fortresses across Puglia, a number of which can be visited. No trip to this fascinating region would be complete without visiting some of these great landmarks.

Due to its location, the large port city of Brindisi on the Adriatic coast of southern Italy, was the target of attacks by sea by Turks and Venetians. There are four large fortress-castles in Brindisi. The Castello Alfonsino is also known by a couple of names: as the Castel Rosso, Castello Di Mare, or Forte a More. This complex, fortified building built on the island of Sant’ Andrea, is located right at the entrance to the port. Construction of it began in 1445, when Alfonso I of Aragon realised he needed to make significant improvements protect the port.

However, the largest and most imposing fortress in Brindisi is the enormous Swabian castle, the Castello Federiciano di Brindisi, sometimes called the Castello Svevo-Aragonese, and also known as the “earth castle” in the heart of the city. The original castle dated from 1227, when Emperor Frederick II and his new bride, Isabella II of Jerusalem were there prior to Frederick’s departure for the Crusade of 1228. The Castello fell under the ownership of a number of rulers and dynasties, including Ferdinand I of Naples, the Republic of Venice, and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. During the 19th century, it was converted into a prison, then finally under the command of the Marina Militare. Visits are free and it’s open all year round, but check with the local tourist office about reserving a place, as visitor numbers are limited to this secure Naval HQ precinct.

About 15kms S.W. of Brindisi, is the town of Mesagne. Its most prominent feature, and the reason to make a detour to visit it, say en route to Ostuni, is its Castello. Dating back to the 11th century, the royal fortress we see today is the result of a major rebuild in 1430. The town of Mesagne has been historically important since the Messapic civilisation, around the 7th century BC. In later ancient times, its location served it very well, as it was on the Roman Appian Way. It served merchants, travellers, locals and of course, the military. All this activity means is that the town has enjoyed a lively atmosphere since early times.

As you enter the old city through the main gate, you will immediately see the city’s very own castello, which was built in the 11th century. Walk around the impressive castello walls and bastions that were erected to defend the city and fend of invaders. Venture inside and you will discover that today it is home to the Archaeological Museum. The small historic centre of town is well worth checking out before you move on. There are a number of fine churches and impressive palaces dotted along the narrow, cobblestone streets, and of course the usual pleasant cafes.

On the Adriatic coast, about 87 kms further south from Brindisi, lies the town of Otranto, Italy’s easternmost town. Situated on the Salento peninsula, the town connects the Adriatic Sea with the Ionian Sea, and looks across the Strait of Otranto towards the Balkans and Greece. Otranto’s strategic location on the Strait has deeply influenced its history and architecture. Originally the site of an ancient Greek city, in Roman times it was an important trading port, and the starting point for Roman military expeditions to the east. In 928 it was sacked by a Fatimid fleet and its inhabitants carried off to North Africa as slaves. It remained in the hands of the Byzantine emperors, and eventually surrendered to the Normans. However, being so exposed to the sea made Otranto vulnerable to attacks across the Adriatic, especially during the 15th century. As a consequence, Otranto became a heavily fortified town, which is very much in evidence today.

To access the old town you pass through the Porta Alfonsina, a gate in the thick perimeter walls that were built after the town was liberated from the Turks in the late 15th century. This gate leads the visitor into the charming UNESCO-recognised Centro Storico, with its maze of narrow, winding streets full of typical shops and restaurants.

You will also come across the Monument to the Martyrs of Otranto, erected to commemorate those who lost their lives defending the city during the Ottoman invasion on 28 July 1480, when a fleet of around 150 ships carrying 18,000 soldiers landed to lay siege to the town. After 2 weeks of resistance and resilience of the townsfolk, the Turks finally stormed the castle and laid waste to the town and its population. All males over 15 were murdered and the women and children sold into slavery. 800 survivors, including the town’s bishop, who had barricaded themselves inside the cathedral, were captured and beheaded after they refused to renounce their Christian faith and convert to Islam. A Papal decree in 1771 formally beatified the 800, who became known as the Blessed Martyrs of Otranto, and were later canonised by Pope Francis on 12 May 2013.

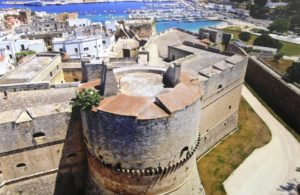

The most dominant sight in the old town though is the majestic Castello Aragonese, built at the end of the 15th century. This mighty fortress, with its ramparts, walls, dungeons, 3 cylindrical towers and a bastion, rises high above the bright blue waters of the Adriatic with its diamond pointed bastion walls extending out to the sea. In 1804, it was obliged to harbour a French garrison during the Napoleonic Wars, and was the location of the allied Italian-French-British Fleet, known as the Otranto Barrage, during WWI.

Access is via a single entrance, over a draw-bridge, and visitors can go right up to the top terrace of the fortress and take in the panoramic view, and where the town’s interesting Archaeological Museum is housed.

Driving down the spectacular coast road one passes small watch-towers and pass by an amazing example of how the hotel industry can interpret an exotic faux “Islamic” architectural fantasy in the small coastal resort of Santa Cesarea Terme.

This c.1920s hotel was under extensive conservation works, so we were unable to access the interior, but the exterior was extraordinary.

Lying about 20 kms. further south from Otranto, in an area dotted with lovely coastal towns and pretty beaches, the town of Castro is often referred to as the ‘Pearl of the Salento’. It’s probably best known as a place of sun and fun in the summer, when it comes alive with bars, seafood restaurants and cafes along the seafront.

Perched 100m above the beach atop a precipitous cliff, the town of Castro looks out across the Adriatic towards Corfu and southern Albania. The town is thought to have been founded by the Greeks, and it’s said that Aeneas, fleeing Troy, landed here. This theory has been verified by recent archaeological digs, including a statuette of Athena Phrygia, which point to a Temple of Athena having been on the site, which is a reasonable explanation for why the Romans called the town Castrum Minervae—Minerva being the Roman equivalent of the Greek goddess Athena.

A bust of Athena’s colossal statue, as well as some highly decorative reliefs, have been discovered near one of the walls. These were buried by the Romans as an expiatory rite of purification after the destruction of the Temple of Athena by Hannibal’s troops in 214 BCE. This enormous statue of the goddess, together with other finds, are on display in the castle. Further digs have also unearthed evidence of Hellenistic fortifications from 4th – 2nd century BCE, that also include the original town walls.

The Angevins—also referred to as Plantagenets and also Normans—took control of the town in the late 12th century, made improvements and increased its size. They commenced construction of an impressive fortress, that was almost certainly over the remains of previous Byzantine, Norman and probably Roman origins. The Angevin castle became one of the most important fortresses in the Angevin kingdom as both protection and for its strategic importance against coastal attacks. What we see today is mostly from the Aragonese period, dating from the 16th century. During this time the castle was stormed twice by the Turks, rebuilt and further strengthened yet again by the Spanish viceroy. It was finally abandoned in the 18th century. Along with the defensive walls and towers, the fortress is one of Castro’s most significant attractions.

On the west Ionian coast of Puglia’s Salento peninsula, about 48 kms across from Castro, lies the beautiful town of Gallipoli. The town’s name means “Beautiful City”, and it certainly lives up it that. Although it may not be as famous as its Turkish namesake, Puglia’s Gallipoli has a long and varied history. The town is divided into two quite separate parts, the modern and the old. The new town includes all the modern buildings, including an enormous, and quite ugly, skyscraper.

The old town centre sits on a tiny limestone island connected to the mainland by a 16th century bridge, and is almost completely surrounded by defensive walls, built mainly in the 14th century. The east side is dominated by an impressive fortress dating back to the 13th century, although it was largely rebuilt in the 1500s, when the town fell under Angevin control.

These fortifications tell us a lot about Gallipoli’s history: thanks to its strategic position, it was frequently under siege. According to legend, the town was founded by Idomeneus from ancient Crete. Mostly likely though, it was a Messapic settlement. The town soon became part of Magna Graecia and remained so until it sided with Taranto and Pyrrhus. Presumably following one too many disastrous victories, Pyrrhus and his forces were defeated by the Romans, who relegated Gallipoli to a Roman colony.

In the early Middle Ages, Gallipoli was sacked by Vandals and the Goths, but rebuilt by the Byzantines. The city flourished economically and socially, due to its geographical position. Later, it was owned by the Roman Popes, and was a centre of fighting against Greek monastic orders.

Its turbulent history continued into the 11th century when it was conquered by the Normans, and in 1268, it was besieged by Charles I of Anjou—the Angevines. The Venetians tried to occupy it in 1484, but failed to do so. King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies started the construction of the port, which by the 18th century, had become the largest olive oil market in the Mediterranean. The oil produced in the region was sent to the city to be marketed and was stored in huge underground cisterns dug into the tufa limestone until sold, when it was then shipped from the port. Due to the importance of this trade, the Vice-Consuls of all the foreign nations involved in the olive oil trade had permanent residences here.

Today, it’s possible to visit two of these underground cisterns, which extend about 200 sq.m. below the D’Acugna and Grassi palazzi in the heart of the old town. A visit to the local tourist office will advise opening hours, which vary according to the season.

Due to its natural configuration, the town had been protected by a fortress and a fortified perimeter since Roman times. Important upgrades took place under the Aragonese dynasty at the end of the 15th century, as part of a wider project to improve and expand the defensive structures of the whole region.

All that was kept of the castle was a polygonal keep, to which 3 round towers with sloped footing and embrasures resting on small arches on brackets were added—useful for defending the fortress from artillery fire. A fifth tower, called a “Rivellino”, separated from the perimeter of the fortress and standing alone in the water, was added a little later. The fortress was completely surrounded by the sea, and it was only a century later that it was linked to the mainland by the bridge.

This is one of the most rewarding fortresses to visit in Puglia. It’s beautifully presented, most of its interior is accessible with very good visuals and explanations, in English as well as Italian, to help the visitor understand its history and function. It also has one of the best book and souvenir shops of any of the castello-fortresses we visited.

The island heart of Gallipoli is home to numerous impressive Baroque churches and palazzi, a testament to the town’s former wealth as a trading port. A labyrinth of narrow, winding streets all eventually lead to the broad sea-front promenade, offering wonderful views. In the summer months cafes, bars and restaurants proliferate along the footpaths. Even in the winter, there were still plenty of great-looking places to eat, drink and relax while enjoying the mild, sunny day.

As you can see from this small selection, there are so many fantastic fortress-castles that are such an identifying feature of Puglia, that contribute to making it one of the most rewarding regions of Italy to visit.