FRÉJUS: SO MUCH MORE THAN A SEASIDE RESORT

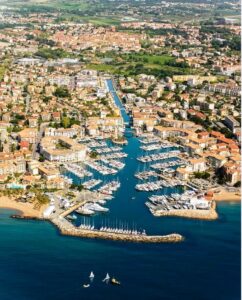

We have driven along the Esterel Corniche (coast road) from Nice heading to St Tropez many times over the years, and have often stopped at the pretty coastal town of Fréjus for lunch at one of the many attractive beachside cafes. We’ve walked around it, enjoyed browsing through the numerous resort-wear shops, or simply rested on a beachside seat and enjoyed the sight of boats bobbing on the calm waters and admired the lovely villas perched above the port. Recently, we decided we would stop off for a short stay and explore the town in depth for a change. We’re so glad we did, and discovered some gems in the town on the hill above the port. We were already aware of its Roman history, but the ruins remaining today are most impressive, testament to its importance in the region’s ancient past.

Merging almost as one with neighbouring Saint Raphaël, Fréjus is one of the best-known seaside resorts on the French Riviera. Extending further along to Saint-Aygulf, the beach has fine sand, and bordered along much of its length by a promenade shaded by palm trees along the pathway. An added attraction is that every Sunday along the seafront, producers, craftspeople and market gardeners offer a wide selection of fresh fruit and vegetables, seafood, local cheeses, cold meats and charcuterie. Stalls also display a large selection of clothing, household utensils, toys, home décor accessories and furniture, as well as flowers and plants.

On Wednesday and Saturday mornings, right in the centre of the historic town, on a hill above the waterfront, local producers and craftspeople fill the nearby streets and picturesque squares with Provençal and Mediterranean flavours and colours of locally-grown herbs, olive oils and wines from the nearby Var region, as well as locally-caught seafood, shellfish and fish, and crafts such as pottery. In the summer months, there’s a delightful night market along the waterfront selling works by local artists and craftspeople, jewellery and fashion accessories, toys and other goodies.

The historic town today is a fascinating and varied testament to the rich cultural heritage of the civilisations that have inhabited the area. The first inhabitants are thought to have been the Celto-Ligurian people, who settled around the natural harbour. The remains of a defensive wall are still visible on Mont Auriasque and Cap Capelin, up in the Massif d’Esterel mountains to the north-east of Fréjus. The Phocaeans (not to be confused with the Phoenicians!) of Marseille later established an outpost on the site.

Fréjus was strategically situated at an important crossroads formed by the Via Julia Augusta—which ran between Italy and the Rhône—and the Via Domitia. Although there are only a few traces of a settlement at that time, it’s known that the poet Cornelius Gallus was born there in 67 BCE. Julius Caesar wanted to supplant Massalia (Marseilles), so established the town as Forum Julii, meaning ‘market of Julius’. The Roman historian Tacitus also named this port “claustra maris”(gateway to the sea). The Forum Julii is mentioned in correspondence between Plancus and Cicero around 43 BCE. It was at Forum Julii that Octavius (who later became the Emperor Augustus) repatriated the galley ships taken from Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, and between 29 and 27 BCE, it became a colony for his veterans of the 8th legion, adding the suffix Octavanorum Colonia.

Augustus made the growing city the capital of the new Roman province of Narbonensis in 22 BCE, which spurred on rapid, new development.

It became one of the most important ports in the Mediterranean, and its port was the only naval base for the Roman fleet of Gaul. It remained operative until the reign of the Emperor Claudius, second only to the port of Ostia in Italy until the time of Nero.

Subsequently, under the reign of Tiberius, the major monuments and amenities still visible today were constructed, namely the amphitheatre, the aqueduct, the lantern, baths and theatre. Impressive walls over 3.70 kms in length were erected to protect an area of around 35 hectares that had about 6,000 inhabitants. It became an important market town for craft and agricultural production. The mining of green sandstone and blue porphyry, as well as fish farming contributed to the thriving economy.

In 40 CE Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who later completed the Roman conquest of Britain, was born in Forum Julii. He was the father-in-law of the historian Tacitus, whose biography of Agricola mentions that Forum Julii was an “ancient and illustrious colony.” The city was also mentioned several times in the writings of Strabo and Pliny the Elder.

In the 4th century, the Diocese of Fréjus was created, which became the second largest after Lyon. The first church was built in 374 with the election of a bishop. However, the decay of the Roman empire led to that of its cities throughout its territories.

Up in Fréjus, the Roman amphitheatre—often referred to as the Arena—dominates. When it was built, it was one of the most imposing in Gaul, with a seating capacity of 12,000 people. Today, it continues to be the venue for shows and performances throughout the year—in line with its original purpose. It’s open from Thursday to Saturday, closed on holidays.

The Romans also built the nearby 1st Century CE theatre that also hosts live shows and an outdoor cinema program in the summer months of June – August. Have a quick look at the aqueduct close by, once over 42 kms long, of which there are a few columns still remaining. Just out of the historic centre of town, on Chemin de la Lanterne d’Auguste, is another monument of the Roman period, the Lantern of Augustus. This 10m high hexagonal structure once stood at the entrance to the port as a landmark for sailors, although it was not, as was once thought, a lighthouse.

The only standing vestige of a vast Roman thermal complex is the Porte d’Orée near rue des Moulins—sometimes inaccurately written as “Porte Dorée”, as it was thought to have been the remains of the southern gate on the edge of the city. Listed as a Historical Monument in 1886, it is located in the northwest of the Roman port, and corresponds to the arch into the cold room (frigidarium) of the baths. The Roman town walls are situated at the Clos de la Tour. The route of the wall follows the relief of the rocky hill on which Fréjus was constructed.

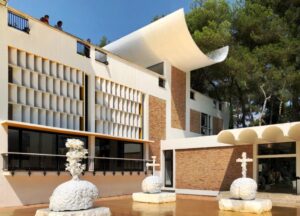

The medieval heart of the town is one of the main drawcards of Fréjus. The centre is the very pretty Place Camille Formigé. Pastel-coloured shuttered townhouses line two sides of the market square while the elegant orange façade of the Hotel de Ville and striking Cité Episcopale, or cathedral close, are along the other sides. Large plane trees and olive trees in tubs, and several delightful-looking cafes complete this typical Provençal scene.

The cathedral of the episcopal group marks the entry of the bishopric in the region in the year 374. Its beautiful octagonal Baptistery (Baptistière) dates from around the early 5th century, just as Roman power was declining. One of the oldest and best preserved examples of early Christian architecture in France, it is adorned with granite columns that have been re-used and date from antiquity, and five of them come from the Turkish city of Ezine.

The octagonal baptismal font was only rediscovered in the 1920s, having been built over in the 13th century. The lovely cloister needed considerable restoration after the Revolution, and again between 1922 and 1931, along with an old well, a former Roman cistern. There’s a very good archaeological museum next to the cloister houses that has a scale model of the Roman town and a fine collection of Roman artefacts, very well displayed.

The first bishop’s residence was built to the south of the cathedral in the 5th century, and later altered in the 11th and 12th centuries. It too was badly damaged during the Revolution and sold as national property at that time. The city of Fréjus bought it and after restoration in 1823, returned it to the church. After the separation of the church and the state in 1905, the city of Fréjus asked for the property back, and the palace officially became the Hotel de Ville of Fréjus in 1912.

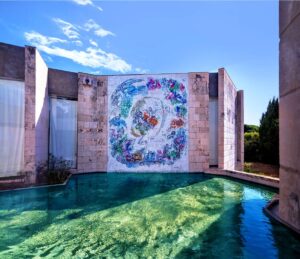

Since 1987, Fréjus has been designated as a “City of Art and History,” which means it has demonstrated a commitment to preserving its archaeological and architectural heritage. The local community and its leadership have been recognised for their awareness and sensitivity for the architectural treasures from all periods and for all time.

Fréjus is also part of the Circuit des Metiers d’Art, that revives a tradition that had died out in the 18th century, which had its origin in the pottery shops located inside the ancient city itself. As a member of the network “City of Artisan Crafts”, Fréjus strives to promote the installation of workshops of local resident artists, which means there is a good selection of these crafts to discover.

There are any number of outdoor terraces and delightful places to eat or simply enjoy a drink in Fréjus and Saint-Raphael—which merge into each other, it’s impossible to say where one ends and the other begins. Aside from the waterfront cafes, a lovely place to have lunch is Place Fevrier, the square near the church in Fréjus.

In and around Fréjus and St Raphael there are also several wineries where you can wander around and taste delicious local wines. Some of the wineries in the area are Les Celliers du Sud at 168 rue Henri Vadon near the Roman Amphitheatre, La Cave des Cariatides in rue Sieyes in the historic centre, and Château de Paquette on Chemin de Curebéasse, Fréjus. There are others somewhat out of town, but ask about all of them at the Tourist Office in Fréjus in rue Jean Jaures in the historic centre.

As well as its pretty beaches, ports full of millionaires’ yachts and many coastal resorts, there is such a lot to see and do in this lovely town, especially its historic centre, which adds a wider dimension to a Riviera holiday.

.