PICTURESQUE PATMOS – THE ISLAND OF REVELATION

The island of Patmos in the Dodecanese group is widely revered as the place where St John the Evangelist wrote the Book of Revelation. We had sailed past the island on a number of occasions in the past but hadn’t stopped off, as we were always en route to somewhere else. This last visit, we determined to add Patmos into our itinerary as we were staying on Kos, only a 2 hour trip on a fast ferry. This beautiful island is relatively small at barely 20 sq. kms, but has a lot to offer for a short, relaxing stay.

Like many Greek islands, Kos does not have an airport, but is quite easily accessible from any of the islands in the Dodecanese group. We had booked in advance as we weren’t sure how much accommodation was readily available, or whether, due to its numerous beaches, most hotels were pre-booked. The fact that Patmos doesn’t have its own airport means it’s not the easiest place to get to for many potential visitors and so it hasn’t been overwhelmed by big hotel developments. It has a certain feeling of disconnectedness, yet it still manages to attract individual visitors who are looking for a quieter escape, rather than a noisy party island. Having said that though, because of its relative quiet and peacefulness, the island often attracts super deluxe yachts of the rich and famous who are seeking such a destination.

We chose a small hotel within a couple of minutes’ walk from the ferry port, just on the edge of the main town of Skala where we went for an afternoon coffee and later dinner each evening. This most appealing town is the island’s commercial and economic centre and offers a surprisingly large selection of very good cafes, tavernas and higher end restaurants dotted around the town square and along the vibrant seafront. You will see a number of excellent shops selling a good selection of resort-wear, accessories and homewares. We also discovered a couple of shops selling Greek body products such as olive oil-based and donkey milk (I kid you not!) creams and potions, and great quality olive oil-based soaps that are mostly unavailable outside Greece.

Some of the great culinary delights of Patmos include the beautiful local honeys and fresh home-grown products. You’ll find seafood cooked in imaginative ways, such as octopus or squid stuffed with rice, raisins and pine nuts, and local cheese pies, which are absolutely unique using a variety of soft and hard cheeses, cinnamon and sugar, resulting in a great combination of sweet and salty.

According to Greek mythology, Patmos was originally named ‘Letois’, after the goddess and huntress of deer, Artemis, daughter of Leto. It was believed that Patmos came into existence thanks to her divine intervention. Artemis had been a frequent visitor to Caria, on the mainland across the shore from Patmos, where she had a shrine on Mount Latmos. There she met the moon goddess Selene, who cast her light on the ocean, revealing the sunken island of Patmos. Artemis then gained her brother Apollo’s help to persuade Zeus to allow the island to rise from the sea.

Very little is known about the earliest inhabitants of the island, and in the Classical period the locals identified themselves as Dorians, descended from the families of Argos, Sparta and Epidaurus, and other peoples of Ionian ancestry. During the 3rd century BCE in the Hellenistic period, the settlement of Patmos acquired an acropolis with improved defences through a fortified wall and towers.

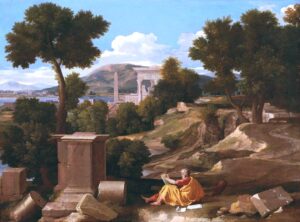

Patmos is mentioned in the Book of Revelation, the last book of the New Testament, which states in its introduction that its author John, had been exiled there from Ephesus as a result of anti-Christian persecution under the Roman Emperor Domitian about 95 CE. Banishment was a common punishment used during the Imperial period for a number of offences, such as magic and astrology. Prophecy was viewed by the Romans as belonging to the same category, whether pagan, Jewish or Christian. Prophecy with political implications, such as that expressed by the Evangelist John, would have been perceived as a threat to Roman power and order.

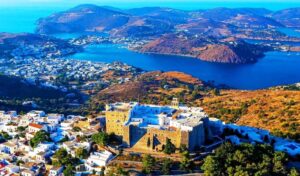

After the death of St John on Patmos, around 100 CE, a number of Early Christian basilicas were erected on the island. Among these was a Grand Royal Basilica in honour of St John, built c.300 – 350 CE at the mountain-top location where the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian stands today. Early Christian life on the island barely survived numerous Muslim raids from the 7th – 9th centuries. During this period the Grand Basilica was destroyed. In 1088, the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos gave Christodoulos Latrinos, the complete authority over the island of Patmos, as well as permission to build a monastery on the island. The construction of this fortified monastery started in 1101. With ramparts 15 m tall and views of the sea in every direction, radiating defiance, it proclaimed itself a last bastion of civilisation.

The population of Patmos expanded considerably by groups of Byzantine immigrants fleeing the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, and Cretan immigrants fleeing the fall of Candia in 1669. However, the island was controlled by the Ottoman Empire for many years, but it enjoyed certain privileges, mostly related to tax-free trade by the monastery, as certified by Ottoman imperial documents held in the Library. Ottoman rule in Patmos was interrupted firstly by Venetian occupation during the Candian War between 1659 and 1669, then Russian occupation during the Orlov Revolt between 1770 and 1774, and finally during the Greek War of Independence of 1821.

In 1912, in connection with the Italo-Turkish War, the Italians occupied all the islands of the Dodecanese (as noted in my last blog about Kos), including Patmos. The Italians remained there until 1943, when Nazi Germany took over the island. The Germans left in 1945, and Patmos remained autonomous until 1948 when, together with the rest of the Dodecanese Islands, it joined with independent Greece.

If you arrive by boat from Athens you are likely to arrive at night. At first you will see what seems an impossibility: a circle of light floating several metres high above the sea. This is Chora, the island’s capital, dominated by the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian right at the top. Of course, if you arrive by boat during the day, the first sight is this massive, fortified monastery dominating on the high hill overlooking the whole island and the port of Skala.

From Skala it’s easy to reach the Monastery by the local bus at the port. The bus leaves you almost at the top, with about 100m to walk up a steep slope, to the high walls and heavy entrance gate into the Monastery precinct. There is a small fee of about 6 Euros, which covers the Monastery and the museum.

As mentioned, the Monastery was founded in 1088 by the Blessed Christodoulos Latrinos of Patmos, an abbot from Nicaea in Bithynia (Iznik today, in northwestern Turkey). The Monastery has been a place of pilgrimage and Greek Orthodox learning ever since. The structure itself is a rather unique complex, integrating a monastery within a heavily fortified enclosure, which has evolved to the changing political and economic circumstances of the island for over 900 years. It has the external appearance of a polygonal castle, with towers, crenelations and ramparts. It is also home to a remarkable collection of manuscripts, icons and liturgical artwork and objects.

The earliest parts of the complex are the Katholikón (main church) of the monastery, the Chapel of Panagia, and the refectory. The beautifully decorated inner courtyard features a well with holy water and a water tank in its centre. Most of these fortifications are fine examples of Byzantine architecture. An arch with 4 curves on the eastern side of the monastery dominates the area and also has many frescoes depicting miracles performed by Saint John.

Around the central courtyard is the main church and the chapel of the Virgin Mary, which houses the oldest frescoes of the monastery, dating from the 11th century. The relic of the founder of the Monastery is kept in the chapel of Agioi Apostoli, constructed in 1603. A further 8 chapels are inside the Monastery complex, which served as the meeting places of the monks. Particularly fascinating is the main chapel which includes beautiful wood-carved icon stand, a marble floor, and rich decoration.

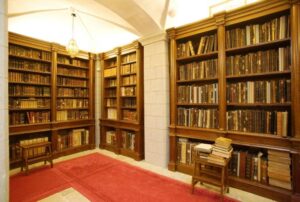

There is a very impressive library, established by Agios Christodoulos, which holds 2,000 volumes, 13,000 documents and 900 manuscripts. Other prized possessions include precious works of ecclesiastic codes, biographies of saints and suchlike.

One of the highlights of the Monastery is the Ecclesiastical Museum. It was established in 1988 in celebration of the 800 years since the foundation of the monastery. The museum features many interesting exhibits, showcasing a vast collection of religious relics and historical items, including superb icons, ecclesiastical utensils, vestments embroidered with silver or gold thread and bejewelled with precious stones, and various other garments that constitute the treasury of the Monastery.

After exploring the Monastery itself, head into the winding maze of streets that make up the town of Chora (sometimes seen spelled as Hora), the actual capital of the island. Every building is whitewashed, many with colourful vines and window boxes perched on high walls, all set closely together into narrow, cobblestoned streets and alleys. The dazzling white of the buildings is in vibrant contrast with the vivid blue of the Aegean glistening in the distance. There are plenty of cafes and little shops in the town selling a mixture of essentials for the local population and tourist souvenirs, most of which, not unsurprisingly, relate to the Monastery and St John.

The gathering place in Chora is the main square, which is lined with a lively selection of restaurants, tavernas and bars. It seems quiet and very empty during the day, but as day mellows into balmy evening, it becomes the focal point that draws everyone to it for a pleasant, friendly night out.

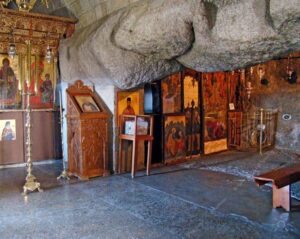

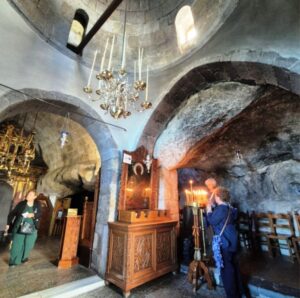

It’s time to head down the hill to the other great attraction on Patmos, the Cave of the Apocalypse, which is approx. halfway up the mountain, along the road between Skala on the coast to Chora. Around 95 CE when St John was exiled to Patmos, he sought refuge in this cave along with his faithful disciple and scribe, Prochorus. It is believed that one day, the rocks of the cave cracked and three fissures were created, which are symbolic of the Holy Trinity. It was through these fissures that God spoke to St John, instructing him write down his visions of the final days of the world and the creation of a new Earth.

The walls are covered with rare icons, many of which date from the 1600s, and there is an ornately carved wooden altarpiece. A visit to the cave is a very moving and reverential experience, as pilgrims can actually touch the fissures on the wall and see the niche on which the Saint used to rest, as well as the rocky protrusions he used in order to prop himself up. The lectern used by Prochorus as he assisted Saint John in his work can also be seen inside the cave. Beyond its spiritual significance, the cave is a veritable time capsule, offering a glimpse into the ancient world.

The austere surroundings, combined with the preserved elements of early Christian worship, allow visitors to step back in time and witness a fragment of the world that shaped the foundations of Christianity. It is important to bear in mind that photography is not allowed inside the cave itself. The Monastery and Cave were declared UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1999.

On your way up to the Monastery and the Cave, you would have seen 3 stone windmills on the ridgeline just below the town of Chora. When you’ve finished your visit to the Monastery, the Cave and Chora, head in the direction of the windmills, just a few minutes down the slope of the hill. Now known as the Windmills of the Monastery of St John the Theologian, two of them were built in 1599 and the third in 1863, when the relatively new technology spread throughout Europe. For millennia people had ground cereals for flour by hand, or using animal power. Water-powered mills were already in use in Roman times, but the knowledge of this technology was lost in many places during Medieval times, and in any case was not suitable for such dry places as Patmos.

Wheat and other cereals have been grown on Patmos since prehistory, and it is believed that the Aegean islands were on one of the main routes along which farming techniques from the Middle East were transmitted to Europe. Windmills caused something of a technological revolution in Europe at the time of the Renaissance, as they represented the first widespread use of large machinery. Farmers would bring their cereals to the millers, many of whom became wealthy from the trade. However, following the Industrial Revolution, flour production was increasingly moved to larger factories powered by steam, then electricity, making the old windmills redundant. Flour production on Patmos finally ceased in the 1950s, and the windmills were abandoned and became derelict.

Since 2009, the windmills have been restored for use as a fine example of conservation, alternative technology, and as a cultural and educational resource, as well as a tourist attraction.

After checking out the windmills, you can either make your way down the hill towards Skala on the well-signposted footpath, or to one of the very enticing beaches that are like a garland around the island’s coastline.

Some of the notable beaches include Petra cove, with excellent tavernas such as Ktima Petra and Flisvos. Adjacent to Petra beach, beyond the strange-looking rocky outcrop honeycombed with caves fashioned by Paleo-Christian hermits, is a small nudist beach. Further around the island is the only pure sand bay, Psili Ammos. This bay isn’t easy to get to on foot, but can be reached by taxi-boat from Skala. Most of the most renowned beaches on Patmos, such as Meloi, lie north of Skala. The best ones face each or south. West-facing bays are inclined to be windy. Others to explore include Meloi, Kambos and Vayia, but there are quite a few more. Virtually all have tavernas and snack bars on their shore, making a beach excursion a great excuse to relax for a day or few hours.

A few days on Patmos is the perfect way to explore one of the most interesting islands in Greece, with historic sites and villages, plus delightful beaches on which to relax and recharge the travel batteries, ready for the next adventure.

Leave a Reply