THE REMARKABLE LIFE OF JOSEPHINE BAKER – CABARET STAR, RESISTANCE HEROINE, ACTIVIST AND OWNER OF A DORDOGNE CHATEAU

Iconic entertainer of the Jazz Age, famous for her risqué performances, Josephine Baker’s extraordinary story is one of perseverance, bravery, and incredible talent. She was a force to be reckoned with, whether fighting racism in her native America or spying on top Nazis. She found new ways to challenge those who sought to diminish or silence her, and innumerable ways to both charm and resist. She has now been honoured in the Panthéon, Paris.

Josephine Baker was born in 1906 in St Louis, Missouri. Her parents were both entertainers who performed throughout the segregated Midwest, often bringing her on stage during their shows. Unfortunately, their careers never took off, her father left never to return, and by the age of eight, young Josephine was forced to take any odd jobs she could manage to find, just to survive.

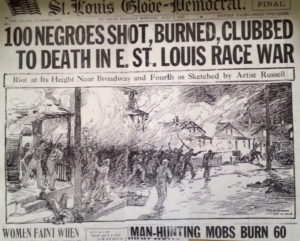

By the age of 15, she had already been married twice and was working full time as a domestic servant, on wages so low she resorted to rifling through garbage bins for food scraps. One white family she worked for as a domestic servant forbade her to look them in the eye, while another burned her hands when she put too much soap in the laundry. In 1917, when she was 11, a terrified Josephine witnessed the terrible racial violence in St Louis. In a speech many years later, she recalled “…watching the glow of burning Negro homes lighting the sky. We children stood huddled together in bewilderment…frighted to death with the screams of the Negro families running across a bridge with nothing but what they had on their backs as their worldly belongs…So with this vision, I ran and ran and ran…”

By the age of 12 she was no longer able to go to school, having instead to find work wherever she could. When she couldn’t obtain work, she lived as a street child in the slums of St Louis, sleeping in cardboard box shelters. She often danced on street corners, collecting money from onlookers, and eventually found work with a street performance group called the Jones Family Band. She married, at the age of 13, Willie Wells, however the marriage lasted less than a year. She struggled to have a good relationship with her mother who had tried, in vain, to prevent her becoming an entertainer. By the age of 15 Josephine had married her second husband, William Baker. She left him when a talent scout invited her to join a vaudeville troupe that was booked into a New York City venue. She divorced Baker in 1925, but kept his surname. During this time she began to see significant career success, and between her professional travels, she would return to St Louis with gifts and money for her mother and younger half-sister.

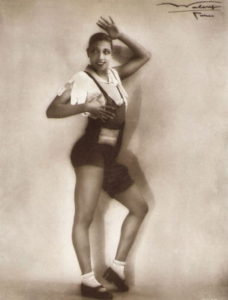

New York in the 1920s saw the rise of the African-American cultural movement, referred to at the time as the New Negro Movement, but nowadays as the Harlem Renaissance, which was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theatre and politics. Josephine performed at the Plantation Club and in the chorus lines of ground-breaking and hugely successful Broadway revues such as ‘Shuffle Along’ , ‘The Chocolate Dandies’ and ‘The Dixie Steppers’. She performed as the last dancer on the end of the chorus line, where her act was to perform in a comic manner, as though she was unable to remember the dance, but at the encore she would perform it not only correctly but with additional complexity. At the time, she was billed as “the highest-paid chorus girl in vaudeville”, and this led to an offer to join a troupe heading to Paris for a tour. France would become her home until her final days.

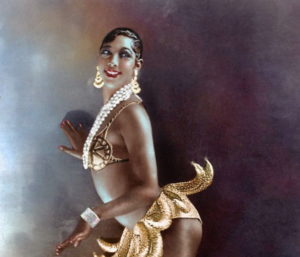

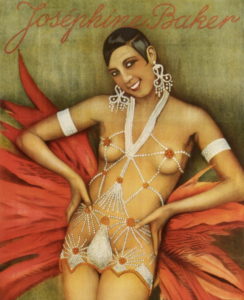

Plucked from the chorus line at the age of 19 to become a headline act, Josephine opened in La Revue Nègre on 02 October 1925 at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées—a white producer’s attempt to bring “authentic” Black American culture to Europe. Josephine was immediately enthralled by Paris. In an interview many years later, she recalled her first impressions about Paris, “What did I see first? Men and women kissing each other in the streets! In America, you were sent to prison for that! This freedom amused me…in the theatres, women could show themselves without clothing. I could not believe it, so I bought dozens of pictures of nude women”. She instinctively knew this was where she belonged.

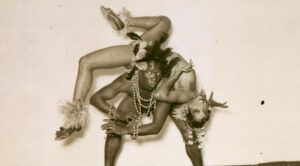

The company rehearsed on the rooftop of the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, accompanied by a saxophonist. She later recalled “Oh! What an intoxication to dance in the sun with practically nothing on. The Charleston should be danced with necklaces of shells wriggling on the skin and making a dry music…it is a way of dancing with your hips. We hide the buttocks too much. They exist. I don’t see what reproach should be offered them.” For her, the skimpy costumes she now wore represented not shame and scandal, but freedom from the oppressive culture which had persecuted her.

After a successful tour of Europe, she broke her contract and returned to Paris in 1926. Within a year of her arrival, she had thrilled audiences with her madcap Charleston, and performed a wild dance in a costume consisting only of a crystal body mesh with a tail of pink flamingo feathers. However, her most notorious dance was the infamous Danse Sauvage at the Folies Bergère, wearing a costume consisting of a low-slung belt made of a string of artificial bananas. It was as though the banana dance was an act of reclamation—taking back ownership of hurtful caricatures and reinventing them on her own terms. Once a tool of derision mocking her race, they could be reclaimed and redefined through costumed performances.

For all her bravado though, she considered that the most astonishing aspect of her almost-overnight success was that “After the show was over, the theatre was turned into a big restaurant, and for the first time in my life, I was invited to sit at a table and eat with white people.” She was also shocked to discover that in France, she could sit anywhere she wished on a train or bus.

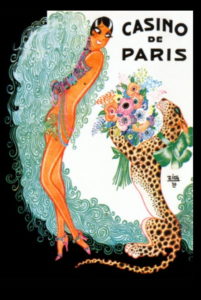

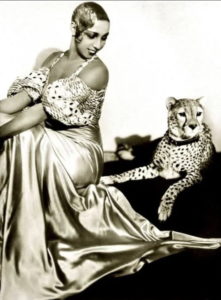

Her success coincided with the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, which gave birth to the term “Art Deco”, as well as a renewal of interest in non-Western art forms, including African. She was often accompanied on stage by her pet cheetah Chiquita, who was adorned with a diamond collar. Chiquita frequently escaped into the orchestra pit, where it terrorised the musicians, adding another element of excitement to the show. Very soon, Josephine was the highest paid entertainer in Europe. Ernest Hemingway called her “the most sensational woman anyone ever saw”. He spent hours talking with her in Paris bars.

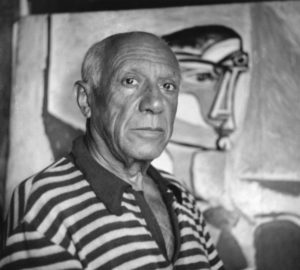

Picasso drew and made sketches and paintings depicting her alluring beauty. Jean Cocteau became a friend and helped vault her to international stardom.

She endorsed products such as a “Bakerfix” hair gel, bananas, shoes and cosmetics amongst other commodities. It seemed as though Parisians implicitly understood her, but sadly, this acceptance was unique to France.

On a 1928 tour, when she stepped outside the comfort zone of Paris and entered the largely Hitler-supporting territory of Vienna, she was met with boos and cries of “black devil”. The church opposite the theatre even rang its bells during her concert to warn people they were “committing a sin” by watching her perform.

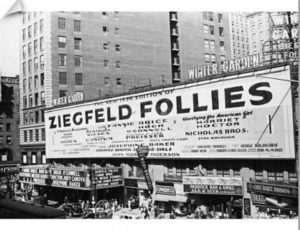

She returned briefly to New York with the show Ziegfeld Follies in 1936, but it was met with harsh criticism, as had films she’d made which had scenes with her dancing with white men, and one film was banned in the U.S.A. because it portrayed a romance between her and a white man. Time magazine, in reviewing the Ziegfeld Follies, referred to her as “just a Negro wench” among other insults. Heartbroken, she returned to France for good, where she became a legal French citizen and gave up her American citizenship. She married the French-Jewish industrialist Jean Lion in 1937 in the town of Crèvecoeur-le-Grand. The marriage was short-lived, although it allowed her husband and his family to flee to the USA in the early days of the war, Josephine saving them from the death camps.

In 1934, she took the lead in a revival of Jacques Offenbach’s opera La Créole, at the Théâtre Marigny on the Champs-Élysées. In preparation for her performances she went through months of training with a vocal coach, and in the words of Shirley Bassey, who cited Josephine as her primary influence, “…she went from a ‘petite danseuse sauvage’ with a decent voice to ‘la grande diva magnifique’…I swear in all my life I have never seen, and probably never shall see again, such a spectacular singer and performer.”

When WW2 began, Josephine knew instantly where her loyalties lay. Every night after performing, she would work tirelessly at the Red Cross homeless shelter on rue du Chevaleret in the 13th arr., bathing elderly refugees and distributing food. In 1940, Jacques Abtey, head of French counter-military intelligence, the Deuxième Bureau, proposed a risky espionage role in the Resistance to her, and Josephine didn’t need to be asked twice. France had offered her unconditional acceptance at a time when her own country—and others in Europe—had literally and metaphorically spat in her face. She simply replied to Abtey that “the Parisians gave me their hearts, and I am ready, Captain, to give them my life. You can use me as you wish”. She was given the rank of lieutenant in the Free French Air Force.

She socialised with high-ranking officials at glitzy galas and parties at enemy embassies, and performed for German soldiers, reporting to Abtey everything she saw and heard. As an exotic foreigner with an American accent, Josephine tricked her targets into thinking she was innocuous and politically neutral: surely a frivolous cabaret dancer had nothing to do with war? Making it her mission to charm information out of every Italian, Japanese or German official or military officer, she discovered the secret locations of troops and airfields, passing on details to help outwit the enemy. While enthralled by her considerable charms, they would scarcely have imagined her sheet music was covered in the secrets she’d discovered, noted down in invisible ink.

As she travelled, she also carried secret messages about troop concentrations and movements, secret airfields and harbours, usually hidden in her underwear, but also written along her arms and on the palm of her hands. She used her stardom and celebrity status to avoid being searched and to move freely around occupied Europe. One of her many deceptions was that she publicly supported Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia. It was the perfect cover for a spy. The vital intelligence she gained also allowed her to pass on information about those who were working for the Nazis in occupied France, or any infiltrators in the French Resistance. As well, she sometimes managed to smuggle secret photos of German military installations out of enemy territory.

By this time, she had first rented and, later bought, the Renaissance Château des Milandes, near Sarlat in the Dordogne, a region that was controlled by the Vichy puppet government, where she sheltered refugees, harboured a huge weapon stash and hid numerous Resistance fighters fleeing capture by the Nazis. She had a few close calls with the Germans, who had gotten wind of the resistance activity happening in the vicinity of the château and even visited it to question her there. Yet again, she successfully charmed and flattered the interrogating Nazis, but she took this last close encounter as a sign that it was time for her and Abtey (who had become her lover by this time) to leave France.

She also used her very real health problems to leave Axis-controlled Europe to visit North Africa’s French colonies, under the pretext of a tour, with Abtey posing as her ballet master, and complete with her menagerie of animals, whom she refused to travel without. In Morocco, Josephine seduced royals and officials, and managed to arrange forged Moroccan passports for Jews, including a member of the Rothschild family, fleeing Europe. Eventually, General de Gaulle instructed both Abtey and Josephine to escape and travel to London via neutral Lisbon. Between them, they carried over 50 highly classified documents and more secret intelligence.

Following D-Day and the liberation of Paris, Josephine returned to her adopted city wearing her military uniform. She quickly took note of the terrible conditions vast numbers of French people endured after the Nazi occupation. She sold many pieces of jewellery and other valuables to raise money to buy food and coal for the poor and to help the homeless.

De Gaulle awarded her the Croix de Guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance, and also named her a Chevalier de Légion d’honneur, the highest order of merit for military and civil action.

Josephine adored children, but suffered a number of miscarriages that ultimately prevented her from having any. Instead, in 1953 she founded what she described as a “Global Village, the Capital of Universal Fraternity” to show how important it is that children of different nationalities and different religions could live together in peace and harmony. She adopted 12 children of different nationalities and religions, forming what she called her “Rainbow Tribe”, who were raised principally at Château des Milandes. She was often absent on tour or back in Paris performing, and things at the château were often chaotic. The château, in effect, had turned into a financial bottomless pit.

As a woman who gradually became “more French than the French”, Josephine had a complicated relationship with her home country. In the decades after WW2, she became increasingly involved in the blossoming American civil rights movement. On one of her first trips back to New York after her Paris success, she was turned away from multiple segregated hotels, and was appalled by the nation’s continuing inequality and injustice. In 1951, she was invited back to America for a nightclub engagement in Miami, where she fought, and won, a public battle over desegregating the club’s audience.

As a result, she began receiving threatening phone calls from members of the Ku Klux Klan, but declared publicly that she was not afraid of them. Actress Grace Kelly sided with her when the famous Stork Club in Manhattan refused to serve Josephine, storming out with her entire entourage, vowing never to return. The two women became close friends after the incident.

Josephine became an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. As a decorated war hero who was bolstered by the racial equality she experienced in France, she was regarded as very controversial, and some black people feared her outspokenness, crusading efforts and racy reputation would hurt their cause.

In 1964, she spoke at the March on Washington at the side of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and wore her Free French uniform emblazoned with her medal of the Légion d’honneur. After Dr King’s assassination, his widow Coretta Scott King approached Josephine to ask if she would take her husband’s place as leader of the Civil Rights Movement. After seriously thinking it over, she declined, saying her children were “too young to lose their mother.”

In 1968, Josephine lost her château owing to unpaid debts. She had even resorted to peeling the gold-leaf tiles off the bathroom walls to give to the bank as collateral. The electricity had been turned off, and her friend Brigitte Bardot, made an appeal on national TV for funds to help her—everyone from Zsa Zsa Gabor to Pope Paul VI donated, allowing her to remain for a while longer at Les Milandes. Eventually, all sources of funds were exhausted.

Her friend, Grace Kelly, now Princess Grace, gave her the Villa Maryvonne in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, between Monaco and Menton, found schools for the children, and paid Josephine to perform at her annual Red Cross gala. Josephine mounted a return to the Paris stage to pay off some of her debts, but suffered a brain haemorrhage shortly afterwards.

She died in Paris in April 1975, and received a full Catholic funeral at L’Église de la Madeleine, attracting tens of thousands of mourners. She remains the only American-born woman to receive full French military honours at her funeral.

After a family service arranged by her friend Princess Grace, she was interred at Monaco’s Cimetière de Monaco.

Today, the Château des Milandes is a museum, honouring Josephine’s life and career, offering visitors a glimpse at the actress, musician, singer, spy, PR whiz and performer, and houses dozens of her costumes and dresses.

Two years ago, a petition was launched in France to have Josephine honoured with a Panthéon burial, the great temple of France that honours illustrious figures have made an outstanding contribution to the history of France.

President Emmanuel Macron agreed, hailing her as a “leading figure of the Resistance and anti-racist fighter” and affirming that she is “the embodiment of the French spirit”. She took take her place as the first entertainer and black woman—and only the sixth woman—to be so honoured in a ceremony at the Panthéon on 30 November 2021.

A coffin draped in the tricolour carrying soils from the US, France and Monaco was deposited inside the domed monument. Her body will stay in Monaco, at the request of her family. As the coffin was borne along a street covered in red carpet to the strains of Baker’s hit song “J’ai deux amours” (“I have two loves”, which she names as “My country and Paris”), images of her life were projected onto the Panthéon’s neo-classical façade. Paying tribute to her in his speech at the ceremony, President Macron said Josephine “did not defend one skin colour” but “fought for the liberty of all”. Addressing his remarks to “dear Josephine”, he said: “You are entering this Panthéon because although you were born American there is no one more French than you.”

Yes . I read about Macron bestowing this honour on her , last week. What an amazing life .

Thanks

Hi Lois,

She was quite a lady–and one can say that she certainly led a full life!

Cheers, Cheryl

What an absolutely fascinating, but largely

unknown, story.

Hi Nadine,

We’re so used to women doing very much as they wish nowadays, yet it’s not hard to imagine what a trailblazer Josephine Baker was in the earlier decades of the 20th century. She broke the mould for originality, that’s for sure! A very courageous lady indeed, who refused to run her life according to others’ wishes or perceptions of how a “good black girl” should act or behave. One of a kind.

Regards, Cheryl

What a fabulous read about a remarkable woman . I didn’t know anything about her .

Many thanks for this opportunity.

Hi Amanda,

Thank you so much for your kind words! I’m delighted you enjoyed the story about Josephine Baker. She was certainly a “one-off”, living life on her own terms, which was quite a feat, given the times she lived in. I’d known about her for many years, and have been past the Chateau de Milandes, and would’ve loved to visit, but unfortunately, it was closed on the day we were in that part of the Dordogne–oh well, next time…She’s such a beloved figure in France, and it’s a pity she’s not particularly well-known elsewhere. I was aware for a while that she was finally going to be honoured in the Pantheon (itself quite an achievement), and saved up writing about her until after the ceremony, as I was wanting to see and source, photos. Wouldn’t it have been an amazing sight?! Best regards, Cheryl

Hi Cheryl,

This is by far the best piece I’ve seen about Josephine Baker. Precise and to the point. Well done, Cheryl, and thanks so much for the peek into a legend.

Cheers,

Frank

Hi Frank,

I very much enjoyed digging deeper into Josephine’s story. I’d long been aware of her in only the broadest sense, and had been curious to know as much as I could. So much of her life story was in fragments, only relating to a particular angle, such as her “scandalous” stage acts; her numerous lovers (of either gender!); her extraordinary wartime exploits; a childhood of extreme poverty and deprivation which later led to her political activism for civil rights, gender equity etc; and of course I certainly knew about the Dordogne chateau, as it’s quite a drawcard in that part of the country, as you no doubt know too. I was keen to try and piece it all together, and so glad you enjoyed it. Cheers, Cheryl