THE MUSÉE MARMOTTAN MONET – A LITTLE-KNOWN GEM IN PARIS

A description that’s often used to describe the Musée Marmottan Monet is that it’s a “hidden” gem. Rather, I’d say it’s perhaps more overlooked than hidden, given its location in the chic Passy neighbourhood in the 16th arr. on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, beside one of the loveliest parks in Paris. Famous for the world’s largest collection of works by Claude Monet, the museum also has works by other Impressionist painters such as Morisot, Degas, Manet, Sisley, Pissarro, Renoir, Gauguin and Signac as well as over 300 masterpieces from the Middle Ages, Renaissance and First Empire period.

The mansion itself was originally built for the Duc de Valmy in about 1864. The land had been part of the estate of the Château de la Muette in Passy, which was broken up and sold off in lots by the revolutionary government in 1790. A considerable part of the château’s land became the Ranelagh pleasure garden, named after the Irish lord who had made such gardens fashionable in London.

When Passy was absorbed into Paris in 1860, the land became municipal property. Baron Haussmann ordered that six hectares be set aside to stay as a park and the garden’s original name of Ranelagh name kept. He decreed that the remaining land giving onto the park be sold off to wealthy buyers who wished to build mansions at this prized location.

One of these buyers was François Christophe Edmond Kellermann, Duc de Valmy. Born in 1835, he was a diplomat, had a seat in the Chamber of Deputies, and was known as a man of letters. He purchased a large plot of land between 20 Ave. Raphaël and 17 Bvd. Suchet on 04 May 1863, for the sum of 137,577 francs. One of the conditions of the sale contract stipulated that a dwelling no less than 600 sq.m. be built within two years. The Duc’s plans were much more ambitious. He subdivided the land into three plots and built townhouses on them, selling the two smaller houses in 1866. He kept the largest property of 2,020 sq. m. for himself, originally to be used as a hunting lodge, but it’s now generally referred to as a townhouse.

Little is known about the Duc’s townhouse, except that the main building had a basement, a first floor and an upper floor, and was flanked by two pavilions, both of which had basements but with only one floor above. The garden was laid out in the fashionable English style, at the end of which, in the right-hand corner, stood an L-shaped blunt-end building comprising a ground level and an upper floor, and there was a small inner courtyard surrounded by glazed walls. It seems that this mansion was not his principal residence, as it has only ever been described as having been a “hunting lodge.” After the Duc’s death in 1868, his widow and daughter couldn’t afford to maintain the property, and it was sold in June 1882 to Jules Marmottan for 260,000 francs.

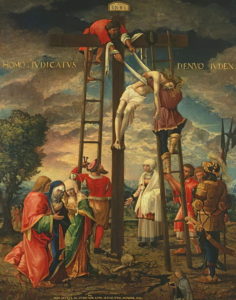

Born in Valenciennes in northern France on 26 December 1829, Marmottan studied law, then worked for a Parisian stockbroker before taking the position of administrator of a number of French energy and transport companies and became involved in their various philanthropic activities. He was an enthusiastic art lover, taking advice from one Antoine Brasseur, a dealer well known for his expertise in Old Master paintings and fine ceramics. Through him, Marmottan acquired some 40 pre-Renaissance paintings from Italy, Flanders and Germany, including an outstanding and rare Descent from the Cross by Hans Muelich painted in 1536, which is still an important painting in the museum’s collection. He also bought wooden statuettes and tapestries depicting lives of the saints, illustrating his taste for medieval and Renaissance art.

Jules Marmottan died in Bordeaux on 10 March 1883, leaving his son Paul a substantial fortune, the townhouse in Ave. Raphaël, as well as his art collections. Paul studied law at the University of Aix-en-Provence and later moved to Paris to train as a barrister. In 1885 he married Gabrielle Rheims but they divorced, childless, in 1894, and he planned to marry Marie Martin. When she died in 1904, Marmottan was left with no heirs, and became somewhat reclusive, turning his interests to studying history and the art of the 1789-1830 periods.

Paul Marmottan became a recognised specialist in the Consulate and Empire periods, building up his own collection of those eras. He redecorated the house’s pavilion in the Empire style where he displayed Carrara marble busts of members of the Emperor’s family, and added furniture that had once belonged to Napoleon when he was in residence at the Tuileries Palace, as well as furniture from the Palazzo Real edi Portici in Naples, once the home of Napoleon’s sister, Caroline, the wife of Prince Murat.

Marmottan also assembled a rare collection of so-called “petits maîtres” of the post-Revolutionary decades, mostly classical-themed landscapes, and some 30 portraits by Louis Léopold Boilly which were hung in the main house. Running off Ave. Raphael the entrance to the museum is at no. 2 rue Louis Boilly.

In 1910 Paul Marmottan acquired land adjoining the townhouse in order to build an extension to re-configure the house to show not only his father’s collection but to present his own. He also redesigned several salons in the main house, along with the bedroom on the second floor, the current dining room and the two round salons on the first floor. He commissioned a series of pilasters, ionic columns, sculpted friezes, while the doors were decorated with antique-inspired dancers and figures striking classical Greek poses.

He acquired new furnishings, including a bed that once belonged to Napoléon 1, more portraits and a very beautiful “geographic clock” in Sèvres porcelain, which is still on display.

Given that his tastes ran very much to traditional classical themes for paintings and art in general, it should come as no great surprise that he abhorred the arrival of the Impressionist movement in the second half of the 19th century. Along with members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, he fought these artists at every opportunity, and was unambiguous in condemning those of his contemporaries who supported them, writing in 1886 that “one does not draw, one sketches; one does not paint, one brushes…That is the most prominent tendency of the day…This slackening comes above all from extreme ignorance or the indulgence of art lovers, who are happy to look merely for the impression.”

The Académie closed the Salon to these young painters after 1870, with the result that they decided to organise their own exhibitions. It was at the first of these alternative salons in 1874, when he first laid eyes on Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet, that the critic Louis Leroy came up with the caustic term ”impressionniste” (see top photo).

Paul Marmottan bequeathed the townhouse to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which inherited it and its collections upon his death on 15 March 1932. Its mission was to champion French art and to preserving the national artistic tradition. This bequest extended its mission as the guardian of a significant part of the national heritage, and it opened the museum to the public on 21 June 1934.

The traditions embodied by the Académie and championed by Marmottan were forced to radically change their obdurate attitude by a large donation of artworks by Victorine Donop de Monchy. She was born in 1863, the year the Duc de Valmy acquired the plot on which the townhouse was built in Ave. Raphael. With her husband Eugène, she was one of the first visitors to the Musée Marmottan and knew it well. As the couple had no children, Victorine decided to donate a large part of the collection she had inherited from her father, Dr. Georges de Bellio.

With the threat of WW2 looming, Victorine made several gifts to the Académie, including Asian objets d’art and paintings and drawings both ancient and modern that illustrated her father’s eclectic tastes. Paintings such as The Drinker by Frans Hals and The Pipe Smoker by Dirck van Baburen would have been very much at home in Paul Marmottan’s former home, but Dr Bellio had also been an early supporter of Claude Monet and his friends. It’s fairly certain that the inclusion in this donation of Impression, Sunrise by Monet and 10 other Impressionist works, would never have darkened Marmottan’s door during his lifetime.

In due course, the Académie recognised the value of Impressionism—perhaps through the influence of new, younger members—especially after the enormous bequest by Michel Monet, the younger son of Claude Monet.

Since the death of his elder brother Jean in 1914, Michel not only inherited the house in Giverny and all the works it contained, he also inherited his father’s collection of paintings and drawings by Delacroix, Boudin, Jongkind, Caillebotte, Renoir and Morisot, as well as his father’s late works, including the monumental canvases of water lilies (fr. nymphéas). The childless Michel made the Musée Marmottan his sole legatee, which included the Giverny house.

When Michel Monet died in 1966, over 100 of his father’s works, including a unique ensemble of Water Lilies canvases, were added to the Museum’s collection. The Académie thus became the owner and guardian of works by Monet, Berthe Morisot, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro and Armand Guillaumin, that formed the cornerstone of the Musée Marmottan’s Impressionist collections.

The salons of Paul Marmottan’s townhouse were too small to show all these works, so a new gallery space was especially designed to be located under the garden. In 1970 these paintings, most of which had never been shown, were finally able to be displayed. They form the world’s biggest collection of works by Claude Monet. The museum then became known as the Musée Marmottan Monet.

Since Michel Monet’s bequest, various other descendants of artists have followed his example, including the Rouart family, who bequeathed the world’s leading collection of works by their forebear, Berthe Morisot. Having lived in the 16th arr. since 1852, the family knew the Musée Marmottan well. As well as 25 paintings by Berthe Morisot, the family donated drawings and paintings by Manet, Edgar Degas and Jean-Baptiste Corot to the Marmottan.

In 1981 Daniel Wildenstein, a member of the Académie and a co-author of Edouard Manet’s catalogue raisonné, donated the collection of illuminated manuscripts owned by his father. This included 322 miniatures by the French, Italian, Flemish and English schools dating from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, which constitute one of the finest collections of such manuscripts in France. The Marmottan has since become a prime location for the study of ancient manuscripts. In 1985, Nelly Duhem, adopted daughter of the painter Henri Duhem, donated his large collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, which included several Monets, to the museum.

Unsurprisingly, the international renown that the Marmottan has enjoyed has come with certain risks. On 27 October 1985, during daylight hours, 5 masked gunmen threatened security personnel and visitors with pistols, and stole 9 paintings from the collection. Among them were Impression, Sunrise, 5 other Monets, At the Ball by Berthe Morisot, Renoir’s Bather Sitting on a Rock and a portrait of Monet by Seiichi Naruse. A tip-off led to the arrest in Japan of a yakuza gangster named Shuinichi Fujikuma, who’d spent 5 years in a French prison for trafficking heroin, where he met two other criminals with whom he carried out the robbery of the Marmottan.

The police found a Marmottan catalogue in Fujikuma’s house with all the stolen paintings circled. It seems he had also circulated this list around a select number of potential buyers, mostly Japanese, who had no qualms about buying art works of dubious provenance. They also found 2 other paintings by Corot stolen in 1984 from another French museum. This find led to the recovery of all the Marmottan’s paintings in a small villa in Corsica in December 1990. It’s thought that the paintings were too “hot” even for those on Fujikuma’s list!

Getting to the Marmottan is easy. The nearest metros are either La Muette or Ranelagh on Line 9. There are a number of buses that stop close by: Lines 22, 32, 52, 63 or 70. We love to wander around the nearby streets admiring the many beautiful mansions in the neighbourhood, many of which are occupied by a number of foreign embassies such as India, Monaco, Afghanistan, Gabon, Madagascar, the Philippines, and the offices of the OECD. A stroll through the beautiful Ranelagh gardens afterwards will take you to La Muette metro station along Chaussée de la Muette.

At No. 19 you’ll see the very pretty Restaurant La Gare, housed in a former railway building. This street also has a couple of other possibilities for a very pleasant lunch, such as La Rotonde de la Muette Brasserie at the busy intersection.

The museum is the perfect size for a most enjoyable visit. Unlike, say, the Louvre whose size is very daunting, with more art than anyone should attempt to see in a week, much less in half a day.

Marmottan, on the other hand, is just right, and perfectly digestible in a single visit—not intimidating in size, yet not too small that it feels underwhelming. Truth to tell, we think the Marmottan Monet has far too much to see to warrant just one short visit. Also, keep your eye out in Paris for posters advertising their special exhibitions, of which they typically hold 3-4 a year.

The upper levels very much resemble a furnished mansion of a very wealthy family, where you can see artworks displayed how they might be in someone’s home—settings that complement rather than overpower.

Although there’s no real connection between the upper levels and the basement, they are perfect spaces to display their contents. On so many levels, Marmottan should be considered a Paris must-do, where you will experience a superlative museum in a beautiful part of Paris that few visitors know about.

Note: Musée Marmottan Monet is closed on Mondays. Also, none of the museum passes are valid for the Museum, so you’ll be up for an entry fee of approx. €12.00.

This museum is sensational & an absolute gem. I had reached the stage where I thought “if I see another Monet Waterlily ….”. The waterlily paintings here are breathtaking with the added bonus of being able to sit down & leisurely take them in. Also we were there in peak tourist season yet it was not at all crowded & no one was standing in your way. Everything about this museum is wonderful, an absolute must see.

[…] It doesn’t matter how many times you see them, they are guaranteed to stop you in your tracks! Their enormous size and wonderful colouration make you feel as though you are immersed in the water lily ponds themselves. There are also magnificent collections of Monet’s works in Paris at the Musée d’Orsay and most especially, the Musée Marmottan Monet. Many art museums around the world have at least one Monet, but if you’ve only time for one, head to the Marmottan. To learn more, have a look at my blog from 2021: https://parisplusplus.com/paris/the-musee-marmottan-monet-a-little-known-gem-in-paris/ […]