THE ALBERT KAHN GARDENS, A HIDDEN PARADISE IN PARIS

We had been aware of this beautiful place in Paris for quite a few years, but due to so many other distractions in the city, had never managed to get there. Whenever we came across a reference to it, or someone mentioned it, typical descriptions were that it was a quiet haven, an exquisite retreat covering 4 hectares, and a little-known, almost-hidden paradise. One glorious, bright sunny day on a recent visit, we were determined to finally get there, after reading an article describing the property’s recent re-opening, following a renovation and restoration project that took 6 years to achieve. And how glad we were that we did!

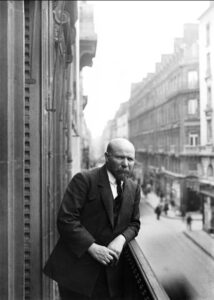

First of all, we wanted to know about Albert Kahn: who was he, and what led him to create this beautiful place? He was born Abraham Kahn in Marmoutier, in the Alsace region, in March 1860, the eldest of six children of Louis Kahn, a cattle dealer, and his wife, Babette Kahn. Babette died when Albert was 10 years old, and after the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine following the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, the Kahn family moved to Saint-Mihiel in north-eastern France in 1872, where he continued his studies until 1876. In 1879, Kahn became a bank clerk in Paris, but studied for a degree in the evenings. He mixed in intellectual circles, making friends with the painter Mathurin Meheut and sculptor Auguste Rodin.

Kahn became a principal associate of the Goudchaux Bank, one of the most important financial houses in Europe at the time. He built up a fortune by speculating first on gold and diamond mines in South Africa, and collaborated with a banking syndicate on industrial projects and international loans. He started his own bank in 1898, at the age of only 38 yrs. While maintaining a busy working life, he resumed his studies at the highly regarded École Normale Supérieure. He became life-long friends with his tutor, to whom he eventually admitted that success in business “was not his dream.”

Albert Kahn settled in Boulogne-sur-Seine, on the banks of the river, in 1893. Initially a tenant in the mansion, he fell in love with the place and bought it two years later.

Once his fortune was made, he started to create philanthropic projects. He was interested in the political and social questions of the time, and set up places where people could debate such issues, get to know one another better, and where Kahn advocated integration and dialogue between populations. His aim was to break down barriers between biological, sociological, political, economic, and geographic differences. He also promoted higher education through a travel scholarship, the Autour du Monde Scholarship, through the Université de Paris, which entailed the recipient to travel for 15 months in a foreign country, and “truly come into contact with life.” In 1905, Kahn opened up these grants, or scholarships, to include young female specialists.

In 1909, he travelled with his chauffeur/photographer to Japan, China and the United States on business and returned with many photographs of their journey. This prompted him to begin a project collecting a photographic record, a sort of inventory project, of the entire Earth.

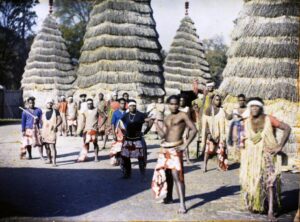

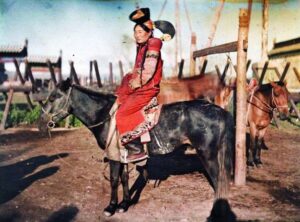

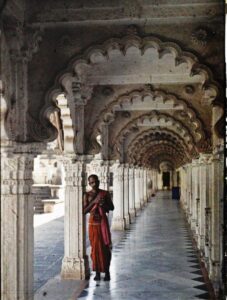

He then sent photographers to every continent to record images of the planet using early colour photography: autochrome plates and early cinematography. Their orders were simple: “Keep your eyes open.” Between 1909 and 1931, they collected over 72,000 colour photographs and 183,000 metres of film, known as The Archives de la Planete.

At his Boulogne-Billancourt property, Kahn maintained facilities for images to be developed, projected and screened. His screenings attracted notable people such as Auguste Rodin, Colette, Auguste Renoir, Henri Bergson and the Nobel prize winner, Rabindranath Tagore. Many of these images form the core of the collection at the museum in the gardens. As well, 69,000 photographs have been digitised and are available online.

photographic collection

In 1914, he initiated the creation of the Comité de Secours National, which aided civilian victims of war, and two years later, he founded the Comité National d’Études Sociales et Politiques (CNESP), where intellectuals got together in order to inform authorities on contemporary issues through their findings and analyses. At the end of WWI he published a manifesto in favour of preventing conflicts, The Droits et Devors des Gouvernements, and created the first centre of social documentation at the École Normale Supérieure in 1920.

Unfortunately, Albert Kahn lost is fortune in the Wall Street Crash and during the Great Depression, and he had to stop funding the bursaries and the Archives of the World project. His bank folded, and he was personally bankrupt. However, by 1936, his property and possessions were safely in the hands of the Departément de la Seine, and he was allowed to remain living in his former home until his death. His gardens were opened to the public, and his photographic collection was put on display. Tragically, when he died in November 1940 shortly after the German Occupation of Paris, because he was Jewish, his body was thrown into a mass grave. Luckily for humanity, his vision has lived on. In 1968, the newly created Departément des Hautes-de-Seine became owner of the Kahn property, gardens, and collection. Today, the museum and gardens attract over 120,000 visitors a year.

During his lifetime, Albert Kahn was an avid gardener, who wanted to create a very special garden based on his humanist philosophy and vision of the world. To this end, he gradually acquired properties adjoining his home, and by1910, he ended up with twenty plots of land covering a total area of 4 hectares. From then until 1920, Kahn decided to create a garden of “scenes.” A great pacifist at heart, he imagined the world in one garden, where different cultures would mingle, in line with his philosophy for the foundation of the Comité National d’Études Sociales et Politiques. He was convinced that knowledge of others would contribute to peace and harmony, and raise awareness of other ways of life. In this way, his gardens enabled the elite of the time to discover the value and richness of cultural diversity, as expressed in the different themes and planting of the garden scenes.

The Vosges forest – intended as a tribute to Albert Kahn’s childhood, it was designed as a reproduction of the Vosges forest where he grew up. There are shady conifers and deciduous trees from the mountains, and blocks of granite strewn along the dirt paths, exactly like a genuine forest.

The golden forest and the meadow – as you leave this wood, an expanse of grass stretches before you, bordered by another forest whose colours change with the seasons: the bright yellow of the spruce trees in spring is replaced in autumn by the golden leaves of birch. The meadow itself brims with the colourful hues of the wild annuals and perennials that bloom there.

The blue forest and the marsh – You move from the warm yellow to the blue of the American Atlas Cedars and Colorado Spruces in the blue forest. Take time to admire the plant species beneath these tall trees, which vary according to the time of year.

The French garden, its orchard and rose garden – Continue on to the orchard and rose-garden, with its orderly layout providing a contrast with the previous areas.

The fruit trees are arranged symmetrically around squares, and the roses climb over arches to form an arbour. Framed by flowerbeds, the garden follows the geometric layout of the classical gardens created in the 17th century. There is a glass and metal great greenhouse standing beside it, which houses the winter garden.

The English garden – in contrast to the French garden, this garden is characterised by lush vegetation grown to imitate nature. The cottage, one of the original buildings, still stands. Its fountain bears a carved image from a La Fontaine fable, and a narrow stream meanders across its lawn to a small pool.

The Japanese village and contemporary garden – The walk ends with a trip to the Land of the Rising Sun, the highlight of the tour. The first part of this classically inspired garden represents a traditional village, with a traditional teahouse and 2 traditional dwellings transported from Japan. The second represents contemporary Japan, created in the 1990s by landscape architect Fumiaki Takano.

The red bridge is an obvious eye-catcher, stretching over the pond where colourful carp zigzag. The path of the water through the garden symbolises the life and work of Albert Kahn and his incredible openness to the rest of the world.

This is one of the loveliest garden environments in Paris. Take a leisurely stroll through the garden, browse through the archives, and imagine what life at the start of the 20th century was like in Asia, Europe, America and Africa, all housed in the beautifully designed new museum, the work of Japanese architect Kengo Kuma.

It’s easy to get to the Albert Kahn Museum and Garden. Take the metro to Pont de Saint-Cloud , which is the last stop on Line 10, and it’s just a couple of minutes from the metro. The street address is: 2, rue du Port, Boulogne-Billancourt. Note: the museum is closed on Mondays, and of course, expect that the garden’s landscape will obviously be different according to the time of year, so bear this in mind when planning a visit, according to what you want to see. Entry fee is about 8 Euros.

As always, I find your articles so very interesting. They make me want to immediately make a booking to travel back to Paris in particular and France in general.

Kind regards,Sally Fox

Hi Sally,

How very kind you are! I’m so delighted that you enjoy the stories, and you must certainly add this beautiful garden to your already very long list of great things to see and do on your next visit to Paris. I know myself that our own list never gets shorter, but gets longer and longer…!

Cheers, Cheryl

What a gem these gardens are. Absolutely

gorgeous.

Hi Nadine,

Yes, they are absolutely sublime. We’ll certainly make a return visit at a different time of year to enjoy the seasonal changes. Such a haven in a busy, crowded city! Cheers, Cheryl