RUE MOUFFETARD – A PARIS STREET PAVED WITH HISTORY

Around every corner of Paris you will find streets full of history. The secret to discovering the real Paris is to detour off the grand boulevards, famous squares and enticing shopping streets. If you delight in discovering special places, little nooks and crannies, narrow, ancient, pedestrianised streets beloved by locals but unknown to most visitors—the rue Mouffetard in the Latin Quarter of the 5th arrondissement is for you.

This ancient, narrow street works in the same way it has for centuries: as a place where people live, shop, eat and meet. Rue Mouffetard runs on a gentle slope from Place de la Contrescarpe down to Square St Médard. Houses, some of which date back nine centuries, line the street, with cafes, all manner of food shops and an outdoor market at its southern terminus that spills out onto the congested, cobblestone street. The upper part of the street is open to traffic, but from its mid-point down, where there is a small École Maternelle (infants’ school), it’s closed to traffic from about 9.00am, enticing the pedestrian to stroll, stop at one of the many cafés, and discover the charm of this ancient street, with many of its buildings dating back more than 900 years.

In a sense, rue Mouffetard represents the history of Paris, with most historians regarding it as the city’s oldest street. Today’s rue Mouffe (or ‘la Mouffe’, as locals affectionately call it) is the remnant of an old Roman road, although long before the Roman legions tramped down its slope it was a well-worn thoroughfare dating back to Neolithic times. The Romans adapted this existing pathway, developing it into a road running from the Roman city of Lutetia, south to Italy. This road runs along one side of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève hill that was called, in Roman times, “mont Cetarius” or “Cetardus”, then Mons Lucotitius.

Rue Mouffetard became the main street of the Bourg St-Médard. Initially, the little village was mostly inhabited by labourers and wine growers who worked the vineyards that grew on the sun-facing slope of Mons Lucotitius. The village’s sunny exposure and rural setting, plus its easy access from the city centre, turned it into a sought-after location. However, the foundation of the Gobelins workshops during the 14th century and the related trades such as butchers, skinners and tanners’ workshops that dumped their waste into the river and streets put an end to the attractiveness of the neighbourhood. The street was then called rue des Moffettes. The French word mouffette means skunk, and mofettes relates to pestilent odours from these businesses. As a result, the quartier was long considered an unhealthy neighbourhood for centuries, but as these enterprises gradually faded away, the street’s name eventually evolved through a variety of versions including Montfétard, Maufetard, rue du Faubourg Saint-Marceau, even rue Saint-Marcel, finally settling on rue Mouffetard.

In the medieval period rue Mouffetard, Place de la Contrescarpe and the neighbouring tangle of little streets sat outside the city walls, making the quartier a mecca for artists, writers, musicians and other creative people, who often lived on the fringe of society.

Due to its location in the shadows of the imposing Panthéon at the top of the hill, Montaigne Sainte-Genevieve and the adjacent streets, including rue Mouffetard, escaped the zealous redevelopment of Baron Haussmann during the reign of Napoleon III in the 1850s. We have the good Baron to thank for keeping this remnant of an old Roman road intact.

Today, rue Mouffetard starts at Place de la Contrascarpe, at its junction with rue de Lacepede. At its northern end, it becomes the rue Descartes, named for the mathematician, scientist and philosopher René Descartes, probably best remembered by most of us for the phrase “Cogito, ergo sum” (I think; therefore I am).

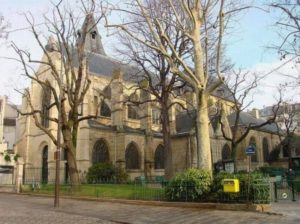

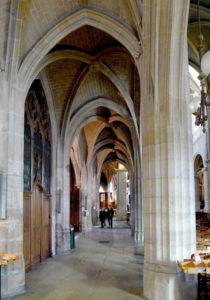

At its southern end, rue Mouffetard now stops at Square Saint-Médard, although originally it extended along what is now Avenue des Gobelins up to Place d’Italie. From the early Middle Ages there has been a church at Square Saint-Médard, although the current church is the result of a rebuild in the flamboyant Gothic style in the 15th century, with a couple of minor modifications during the 18th century. The church acts as a sort of anchor to this end of the street. St Médard is said to be the most invoked patron saint in France, as his name is associated with the weather, so it’s easy to understand how he became the patron saint of farmers, as well as winemakers and brewers. Farmers monitor the weather particularly on 08 June, the feast day of St Médard.

In the 18th century St Médard was the centre of a strange masochistic religious sect called the Convulsionnaires. They were a group of religious pilgrims who experienced convulsions as a way of receiving miraculous revelations. They were prone to contortions, hysterics, violently foaming at the mouth and other bizarre spectacles. Onlookers used to gather outside the church to watch the members speak in tongues, bark like dogs and swallow glass and hot coals until they collapsed on the street. The spectacles were eventually banned by the King himself, who had a prohibition notice nailed to the church door declaring that “By order of the King, God is forbidden to work miracles in this place”.

The church escaped destruction during the Revolution as it was converted into a Temple of Work. Despite being situated at the bottom of the lively rue Mouffetard, it’s a pity that the church is so little-known to tourists as it has a wealth of architectural and artistic features. There are murals and numerous notable paintings including works by Champaigne and Watteau, as well as a fine Gobelins tapestry and magnificent 16th century stained glass as well as a contemporary window dating from 1941. The very fine organ was listed as an Historic Monument in 1980. There is a delightful public garden built over an old cemetery adjoining the church’s southern side, making it a very pleasant spot to rest and relax awhile.

On Sunday mornings, grouped around the footpath in front of St Médard and spilling onto the street, a small local band of musicians including an accordionist and a singer, perform well-known classic French chansons. Song sheets are handed out to encourage onlookers to join in, while others dance. All ages join in, and it’s especially lovely to see older residents, a number of whom may perhaps live alone, dancing with each other, while others without a partner will ask anyone, including total strangers, to dance with them. It’s not turned on for tourists, but rather, it’s simply a local event that brings everyone together, and also welcomes anyone into the rue Mouffe fold. We’ve whiled away many an hour watching, and sometimes participating in this very convivial local gathering. It’s one of the many things that make us feel we’re back “home” each time we return to our much-loved rue Mouffe.

Opposite the church at no. 134, a centuries-old house has an extraordinary painted “Sgraffito” façade, a technique widely used in the Renaissance, and again during the Art Nouveau period, depicting pastoral scenes and animal such as pigs, deer, goats, game and poultry of all kinds—not surprising, as the ground floor shop has always been a charcuterie! Although this decorative art can be found in Art Nouveau-influenced cities such as Brussels or Prague, there’s no other quite like it anywhere in Paris.

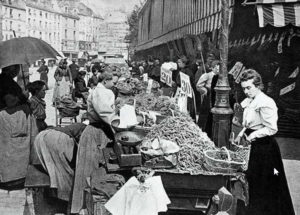

At the church end of the street there’s the historic market, awash with colour, spilling onto the street with a huge array of beautifully presented fresh produce from Tuesday to Sunday. Walking up the gentle slope of this narrow, cobble-stone street, shops have tables displaying fruit, vegetables, wedges of cheese, fresh oysters and other seafood delights.

The scent coming from two great patisseries of freshly baked croissants and a variety of breads such as different types of baguettes, robust country loaves, warm brioches and fruit flans, waft along this end of the street—and the long queues outside testify to their quality.

One of the excellent boucheries always has a rotisserie full of roasting chickens with cubes of potatoes below cooking in the dripping chicken juices; there are large glass display cases full of their own charcuterie, while others have ready-to-cook meats such as pork stuffed with apricots and prunes, seasoned rolls of veal, or the best beef cuts in the city.

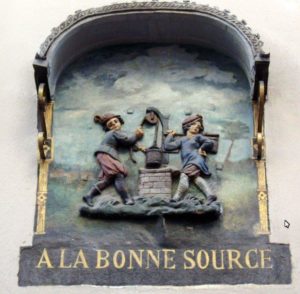

Opposite the butcher at no. 122 is a handy little Franprix supermarket that has a most unusual painted relief above the ground floor inscribed ‘A la Bonne Source’, which apparently is the slogan of the society that started this very old supermarket company.

It’s no wonder our street is known as a “food heaven”, and luckily for us, to accompany all this great food, there are three wine shops in the street. Two are branches of well-regarded chain stores, but our favourite by far is La Fontaine aux Vins at no. 107. Owned and operated by a husband and wife team, Raymond and Michele plus their son, it’s an Aladdin’s cave of incredible wines and spirits. Early each morning you’ll see Raymond outside setting up rows of traditional timber wine boxes stacked full of interesting wines and his little tasting stand made from, appropriately enough, an upturned old wine barrel.

Ready with lots of great advice, we ask their recommendations for whatever we’re going to cook for dinner, knowing it will often be something we’ve never heard of or tried. They’re never tempted to “up-sell”, and love to have our feedback when we see them the next day. If you want to buy something (for us it’s usually Armagnac and Calvados) to take home, they’ll pack it for you in lots of bubble wrap for travel. These purchases go into our suitcases (in the middle, tightly packed with clothing all around) and in all the years we’ve done this, we’ve never had a breakage. Tell them we sent you!

Halfway up the street, past the variety of speciality cheese shops—notably the famous Androuet at no. 134—chocolatiers, bistros and little boutiques, you will see a small bar called ‘Le Vieux Chêne’ (The Old Oak) at no. 69. This friendly little watering hole is one of the oldest in Paris, dating from the early 18th century. It’s had quite a colourful history: it became the seat of a revolutionary committee in 1848 whose aim was to finally overthrow the monarchy—which succeeded. Look up and you’ll see, at first floor level, the bar’s historic emblem of an oak tree.

Wandering further along you’ll pass the huge, stone Garde Républicaine building with its massive iron doors firmly closed on its rue Mouffetard side, but if you walk around to its main entrance on Place Monge, the gates are always open, so you can at least peer into the courtyard. The Garde Republicaine is the emblematic Gendarmerie force renowned for its cavalry regiment, responsible for providing guards of honour for the state, and security in the Paris area. Its missions include guarding important public buildings such as the Élysée Palace, Hotel Matignon (residence of the Prime Minister), the Palais du Luxembourg (the Senate), and Palais de Justice, among others. Its name derives from the Municipal Guard of Paris, established in 1803 by Napoleon. These days, the regiment’s horses are located at the barracks on Boulevard Henri IV in the 4th arr. The 140 horses housed there are selected for their personality, attractive physique and robustness.

If you are ever lucky enough to be in Paris when a foreign dignitary is being welcomed by the President at the Élysée Palace, you will see the mounted guard of honour, all decked out in their magnificent dress uniforms. As a fascinating bit of trivia, each rider has his own horse and is responsible for picking up his horse’s poo after training, and because all is recycled, the mushroom growers of Paris collect it twice a week and use it as fertilizer. There is a very interesting museum dedicated to the regiment’s history at Bvd Henri IV, and the complex is open to the public once a year on Heritage Days in September. Otherwise, you can book a group tour at other times. However, it’s best to avoid a summer visit, as the horses will be away on their annual holiday at a rural stud farm!

Heading up rue Mouffetard, on the corner of rue Ortolan, you’ll pass a delightful bookshop called ‘L’Arbre du Voyageur’. Diagonally across the street is the Fontaine du Pot au Fer. It was built in 1624 when Marie de Medicis commissioned the restoration of the old Roman aqueduct in order to supply water to her nearby Palais du Luxembourg and its gardens. The fountain still runs with fresh water.

The somewhat unprepossessing building at no. 51-53 shot to fame back in 1938 when a hoard of 3,556 Louis XIV gold coins were discovered in a cavity in the wall of the building, which was being renovated. These beautiful coins can now be seen on display at the recently opened Musée Monnaie de Paris (Paris Mint) at no. 11, Quai de Conti in St Germain des Pres. An interesting side note is that the museum has been raising funds for the restoration of Notre Dame Cathedral by selling medals cast at the museum.

One of the best-loved shops further up the street is Alberto’s Gelateria. They sculpt scoops of their superlative gelato into flower forms directly onto the cone before handing it to you. Quite a spectacle, but the main thing is that it’s the best gelato you’ll find outside of Italy.

Past yet more bistros and food shops, notably L’Assiette aux Fromages, you’ll come to Contrescarpe, which defines the top end of rue Mouffetard. Bistros ring the square, lined with the classic rattan café chairs in various colours, all facing out onto the centre of the place. Surrounded by lamp posts, an elegant fountain sits in the centre, within a ring of hedges. Buskers are often found here, entertaining the patrons and passersby.

Numerous streets branch off Contrescarpe. The area has been an inspiration to numerous literary figures in the past. Ernest Hemingway and his first wife Hadley lived in Paris from 1921 to 1928 and returned several times thereafter. They rented a tiny two-room flat at 74, rue du Cardinal Lemoine and as well, Ernest rented a small space around the corner at 39 rue Descartes just for writing, where he penned ‘A Moveable Feast’ in the early 1920s. This tiny former hotel is also where the French poet Paul Verlaine died in January 1896. There’s a plaque on the first floor wall above La Maison de Verlaine café noting this, but nothing about Hemingway on the exterior, although inside the café there’s a wall with memorabilia including a plaque noting both Verlaine’s and Hemingway’s occupancy.

Hemingway remarked that their flat had no hot water or toilet, “although not uncomfortable to anyone who was used to a Michigan outhouse” but it had “a fine view and a good mattress.” Calling it “a wonderful narrow crowded market street,” he evokes images of rue Mouffetard in its more rustic time, when goatherds would wander up and down the narrow cobblestoned street selling fresh goats’ milk to its residents. He also described it as a dirty, wet street full of drunkards, and Café des Amateurs (now Café Delmas) on Contrescarpe, as “a cesspool”. How times have changed!

Although he wasn’t present in Paris, Victor Hugo said he was inspired by these streets in the Latin Quarter at the time of writing his epic story, Les Misérables. The streetscape of rue Mouffetard has provided a backdrop for numerous films, including scenes from the much-loved Amélie, Kieslowski’s Trois Couleurs: Bleu, starring Juliette Binoche, and Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

One of the great attractions of the neighbourhood just behind rue Mouffetard, where the metro station is located at Place Monge, is where the outdoor market is held three mornings a week: Wednesday, Friday and Sunday. Regarded as one of the best produce markets in Paris (there are over 80 regular markets across the city), it attracts people from all over for its quality produce, much of which is certified organic. If you can only get to one, the Sunday market is the busiest and biggest.

Like every other regular, we too have favourite vendors, including two non-food traders, Tarik Assrir, who originally hails from Morocco, selling the most delectable mustards and condiments. As well as regular sized jars, he has little “sample” pots for about €2 ea., which are perfect for little gifts.

Our other “must visit” vendor is an Indian man, Salaria Gamaruddin, who sells the most beautiful pashminas and scarves at incredible prices (better, or as good as I’ve ever paid in India)—we both have numerous, and are always tempted to acquire “just one more”!

A lovely way to finish your exploration of the neighbourhood is to continue for another few minutes further up past Contrescarpe and you’ll come to the magnificent Panthéon, one of the great historic icons of the city and not to be missed.

Another suggestion, especially as a finale to a visit to Place Monge market, is to head across to visit the Grande Mosquée de Paris, which is located a few minutes’ walk away. You’ll see the distinctive minaret as you get closer. It’s a 1920s Art Deco masterpiece and a listed historic monument which you can visit for a couple of Euros (although not on a Friday, unless you’re Muslim). Aside from the lovely internal courtyard with its water features and flowering trees, one of the main attractions is their beautiful, atmospheric salon de thé/café which serves traditional tajines, delicious Moroccan pastries, copious cups of mint tea and suchlike.

The décor is beautiful, and it’s as though you’ve suddenly been transported on a magic carpet to Morocco, Algeria or Tunisia. It’s extremely popular with locals and a favourite of ours, and to walk off our lunch, and too many sweet treats, we take a leisurely stroll through the Jardin de Plantes, just across the street.

If you think you know Paris quite well and look forward to exploring its lesser-known attractions with an authentic Parisian atmosphere, the rue Mouffetard and its neighbourhood will offer that perfect, memorable experience.

“If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris…then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

Just great Cheryl what a wealth of information, will be wonderful when we can travel

Hi Sandy,

At least we’ve got lots of great things to do when the world situation improves and we’re allowed “out” again!

Cheers, Cheryl

Wonderful Cheryl as always. It made my emotions soar – it brought the area to life again with an overwhelming joy, but it also sent me into a great sadness, thinking about what the people of Paris are going through at the moment. But, it, them and us, will rise again!

Hi Jen,

Lovely to hear from you, and thank you so much for your kind words. Yes, it was very much with mixed emotions as I wrote the article, as you can imagine! Won’t it be terrific when we can return and revisit favourite haunts, and do all the special things one can only do in Paris. Can’t wait!

Best regards,

Cheryl