THE MAGNIFICENT BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE DE FRANCE HAS FINALLY RE-OPENED

We had been walking past this enormous complex for years speculating about when it might re-open, wondering if we’d ever get to visit it one day. Imagine our surprise and delight when we saw the enormous posters announcing its re-opening in the metro stations on our first day back in Paris! It was still closed on our earlier visit in April, with no hint as to when it would re-open. This is arguably the most important, and certainly largest, of the numerous new projects in the city that have been completed since COVID hit. No longer dark and rather gloomy, the newly renovated library buildings are a triumph of light and welcoming spaces. There’s such a wealth of wonderful new sights to discover in Paris, and the historic Bibliothèque Nationale de France is surely the jewel in the crown!

To great fanfare at the official re-opening by President Macron, the weekend of 17-18 September marked the end of a massive restoration project that took about twelve years to complete, at an estimated cost of over 261 million Euros. One of the most notable changes is that the Richelieu site, the historic home of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) is now open to all, not, as previously, just to academics and professional researchers. The BnF says that it is returning to one of its key missions, to provide access to knowledge and culture for all, in a magnificent setting. The public can now enjoy free entry to use the reading rooms and admire the stunning architecture, and for a fee of €10, entry to the new museum.

The BnF is located in the heart of Paris, close to the city’s most iconic sites: the Louvre, the Musée des Arts Decoratifs (MAD), the Tuileries, the Palais Royal, the Comédie Française, and more. Today, this complex is referred as “the Richelieu site” in order to distinguish it from the enormous glass towers built to resemble open books, that form the new national library, the Bibliothèque François Mitterrand. This is now the library of France, the national repository of all that is published in France, and also holds extensive historical collections.

By the 1970s the collections of the BnF Richelieu were so immense that the library had become too small to accommodate the collection, hence the necessity of a new facility, which aimed to be one of the most modern, up-to-date and largest in the world. This library was inaugurated in December 1996, and is located on the edge of the 13th arr. on the banks of the Seine at Quai François Mauriac, directly opposite Parc de Bercy.

The Richelieu site is the historic cradle of France’s national library. Built in the 17th century, it was originally the palace of Cardinal Mazarin, and in 1721 the King’s library moved there. The royal library was founded at the Palais du Louvre by King Charles V in 1368. Charles had received a collection of manuscripts from his predecessor, and transferred them to the Louvre from the Palais de la Cité.

For the first time a catalogue, an Inventoire des Livres, was made by the king’s valet, who is regarded as the first dedicated librarian. Charles V was a patron of all forms of learning and encouraged the production and collection of books. At the death of Charles VI in 1422, this entire first collection was bought by John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford and 3rd son of King Henry VI of England, who commanded the English armies in France during a phase of the Hundred Years’ War. He transferred the collection to England in 1424, and it was dispersed at his death in 1435.

Charles VII did little to replace these books, but the invention of printing resulted in the start of another collection in the Louvre inherited by Louis IX in 1461. It was added to by Charles VIII after he seized a part of the collection of the kings of Aragon. Louis XII, who had inherited the library at Blois, incorporated those books into the Bibliothèque du Roi (King’s Library) and further enriched it with plunder from Milan. In 1534, François I transferred the royal collection to Fontainebleau and merged it with his private library. During his reign, fine bindings became all the rage, and many of the books added by him and Henri II are regarded as masterpieces of the book binder’s art.

In the 16th century as it grew in size, the collection relocated several times to ever-larger sites in Paris, a process during which many treasures were lost. Henri IV had it moved to the Collège de Clermont in 1595, a year after the expulsion of the Jesuits from this establishment. In 1604 the Jesuits were allowed to return, and the collection was moved to the Cordeliers Convent, then in 1622 to the nearby Confrerie de Saint-Côme et de Saint-Damien on rue de la Harpe. At this location, the appointed librarian initiated a period of development and acquisition that made it the largest and richest collection of books in the world.

Cardinal Mazarin acquired the Hôtel Tubeuf in 1643, then gradually all the land between rues Richelieu, Colbert, Vivienne, and des Petits-Champs to create a huge palace for himself near the Palais Royal, the main residence of the regent Anne of Austria and her young son who had become king on the death of Louis XIII in 1643.

In 1644, Mazarin commissioned the first major expansion project from François Mansart, who restored and refreshed the classical architecture and erected a brick and stone wing behind the Hôtel Tubeuf along the rue Vivienne garden. This new building comprised two galleries, the current Mansart and Mazarin galleries, serving as a showcase for the cardinal’s collection of artworks–he was considered one of the greatest collectors in Europe at that time.

The decoration of the new galleries was entrusted to a number of Italian artists, including Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, who painted the frescoes on the vaulted ceiling of the upper gallery in 1646-47 with scenes inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

In 1721, the first prints from the Royal Library entered the Mazarin Palace at the behest of the King. This move marked the beginning of an inseparable link between the Library and the palace, forming the foundation of what became known as the “Richelieu site” of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

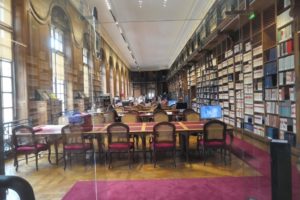

With these additions, the library became very cramped, necessitating further adaptations and additions by the king’s architect, Robert de Cotte. He completed a new gallery on the east wing of the main courtyard in 1735, which is now the reading room for manuscripts and music. At the back of this new wing De Cotte built the Globes pavilion, where a number of enormous, and historically important, globe maps are now displayed.

The collection grew rapidly during the Revolution, when the libraries of aristocrats and clergymen were plundered and their treasures brought here to the Bibliothèque du Roi, hastily renamed the Bibliothèque Nationale. Napoleon, who had an extensive collection of books of his own, took a great interest in the library and he ruled that a copy of any book held in a provincial library which the Bibliothèque Nationale did not possess should be forwarded to it. He declared that it should be possible to find a copy of any book in France in the national library. Today, it is still a “national repository library”, that is, one which keeps a copy of every book published in France.

In the middle of the 19th century, the library became what we would all recognise as a modern library. The architect Henri Labrouste reconstructed the spaces in order to rationalise the management and conservation of the collections. He separated areas for conservation, storage, reading rooms and service areas for staff. The library no longer was made to adapt to the Palais Mazarin, rather, Labrouste converted the palace into a modern library, even if it meant demolition of parts of the historic buildings, thus giving the site its current configuration. The library first opened to the public in 1868.

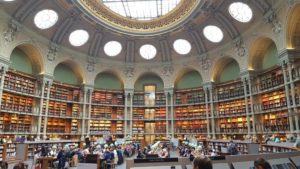

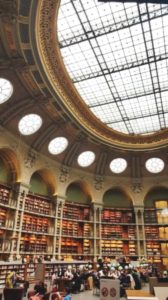

Listed as a historic monument since 1983, the Labrouste Room, usually referred to as the Reading Room, built between 1861 and 1868, is Henri Labrouste’s masterpiece, and arguably the most spectacular space in the BnF. Since 2016, it has been the reading room of the library of the National Institute of Art History. Recalling the architecture of Byzantium, the room is lit by 9 domes, covered with earthenware tiles which diffuse a uniform light into the room. These domes rest of iron arches on 16 slender cast-iron columns, giving the space an extraordinary light and airy effect. The perimeter of the room is adorned with medallions of 36 men and “a woman” of letters from different countries such as Homer Cicero, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Racine—the one woman being Madame de Sévigné.

Despite the major works carried out Labrouste, the BnF still did not manage to meet its space needs, mostly due to the continual growth of the collections. The Salle Ovale (Oval Room) was the final addition to the site. Construction started in 1897, completed in 1932, and inaugurated in December 1936 by the President of the Republic. It is an enormous oval space, measuring approx. 44m by 33m, and 18m high.

The ceiling is a glass-panelled central canopy surrounded by an elegant interlacing of golden acanthus leaves, the upper part of the oval is pierced with 16 glazed oculi (bulls’ eyes) surrounded by mosaics. Above each of the oculi is inscribed the name of a city famous for its symbolic significance in the history of civilisations and libraries. These oculi surmount arches which are supported by 16 cast-iron columns with ionic capitals. The whole effect is visually stunning.

As already mentioned, the library, including the Salle Ovale and the Reading Room, is free and open to all. The only space that attracts an entry fee is the museum. This covers 1,200 sq.m. and is intended to display some 900 items at a time, drawn from the Bibliothèque Nationale’s collection of 40 million pieces. The opening display, which will run for a year, focusses on a selection of the most prestigious artefacts, and there will also be thrice-yearly new exhibitions, all drawing on different, quintessentially French, themes.

For each display, the curators will select not just from the library’s 20 million manuscripts and books, but also from its vast collections of sketches, engravings, photographs, maps, coins, medals and jewellery. There will also be temporary exhibitions in some of the galleries, beginning with one on Moliere, a fitting way to mark the 400th centennial since the playwright’s birth.

In the museum you can admire relics from Charlemagne to Voltaire, the manuscripts of Les Misérables by Victor Hugo, Pascal’s Pensées, the original, hand-written steamy memoirs of Casanova, the original score of Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, original works by Leger, Matisse, Toulouse Lautrec, Chagall, and Picasso, and a 16th century globe, said to be the first to use the word “America”.

As you enter the museum you won’t be able to miss seeing the Great Cameo of France, and the Throne of Dagobert. This is a bronze folding chair made in the early Middle Ages, around the 8th century, and was in constant use until the fall of the ancien régime. Napoleon I used the throne at his coronation ceremony on 02 December 1804–the last time it was used.

There are vast collections of costumes, illuminated manuscripts, including the exquisite 13th century Psalter of Saint Louis, ancient coins and medals, classical sculpture, Greek and Roman pottery, ceramics and beautiful silverware, along with other treasures from antiquity, including a Michaux stone (a type of stone document) from Babylon with Arkkadian inscriptions, numerous paintings, lithographs and historic maps. The prints and photographs alone number around 15 million items! As you can see, the museum is well worth a visit.

While there, you can also have a light lunch or snack in the café, the Rose Bakery, which is open all day. Then head outside to enjoy the gardens, the Jardin Vivienne, that have been carefully redesigned under the title of a Hortus Papyrifera, or “paper garden”, featuring a range of plants used in the production and conservation of paper.

The Bibliothèque Nationale de France-Richelieu lies just behind the gardens of the Palais Royal. The entrance for individuals is at no. 5 rue Vivienne. The Bibliothèque is en route if you are walking from the Louvre to the Opéra Garnier, so it can easily be added into an itinerary exploring the heart of royal Paris. Once the preserve of the few, the librarians have said that they hope visitors will stop off to “read, study, contemplate, or just visit”. For here can be found two precious and very French commodities: le savoir et la culture—knowledge and culture. Note that the library is closed on Mondays. Opening hours are 10.00am – 6.00pm, although closing time on Tuesdays is 8.00pm.

Brilliantissimo! Magnifique …

Merci à vous, Cheryl et Graham.

A xx

Bonjour Chere Anna,

Merci muchly for your warm words of praise! So glad you enjoyed the story. As I said, we’d been speculating for years when/if we’d ever get to visit this, and lo! there it was! Opened at long last. I must say, it is a total knockout, and a credit to the French themselves for being prepared to spend the vast sum required to accomplish this, especially given all the other needs of society these days. Goes to show what high value they put on les choses culturelles–they’d man the barricades (again) to defend it.