STEPPING BACK IN TIME: DISCOVERING ROMAN PARIS

There aren’t many regions in Western Europe that were not once occupied by the Romans, and the city of Paris is no exception. When we think of modern day Paris, it’s probably more likely to be medieval marvels such as Notre Dame or Sainte Chapelle, perhaps monuments of the French Renaissance, Classical revival, the Belle Epoque, and of course the boulevards lined with elegant 19th century Haussmann-era apartment buildings, that spring to mind. However, the origins of the City of Light that we all know and love started with the Romans.

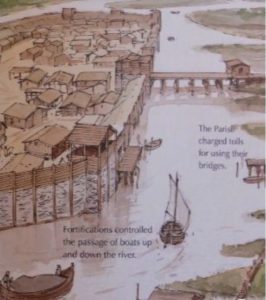

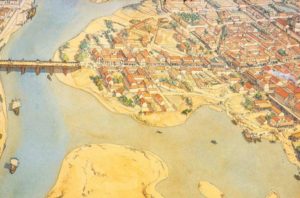

The Île de la Cité and the surrounding area along the banks of the river were originally inhabited by the Parisii, an Iron Age Celtic tribe who occupied the area from the 3rd century BCE until the Roman conquest in 52 BCE. These Celts—whom the Romans called Gauls—named their settlement Leucotecia, meaning ‘marsh’. Although not the first people to inhabit the banks of the Seine, they were the first to establish ongoing communities. They sowed grains, minted coins, traded with tribes as far away as Germany and Spain, built toll bridges, and enclosed their settlement with a wall, the first of eight walls built around Paris over the centuries.

Traces of the Roman ramparts and walls, discovered in 1898, can be found on the Île de la Cité, in rue de la Colombe, next to the wine bar at no. 4. At no. 5 you can see a small plaque acknowledging the wall’s origins.

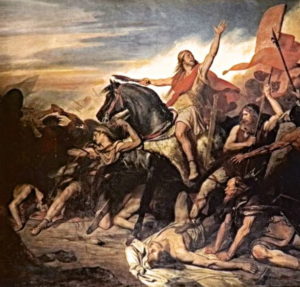

During the 40 year rule of Julius Caesar, the Romans launched numerous military campaigns against the Celts, killing them in their thousands and destroying their culture. Led by Vercingétorix the chief of the Arverni (modern day Auvergne), and Camulogène, the chief of the Parisii, the Celts rose up against Caesar in 52 BCE. Camulogne died in the battle of Lutetia on the land that now forms the flat area around the rue de Vaugirard, which stretches from the Latin Quarter towards the edge of Paris at the Porte de Versailles in the 15th arr. The rue Camulogène in the 15th arr. is named for him, to honour his defence of his homeland that would one day become the city of Paris.

As for Vercingétorix, after the battle of Alesia in September 52 BCE he was captured and taken in chains to Rome. He was held prisoner for almost 6 years before being paraded as a prize in the first of four triumphs celebrating Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, and then executed by strangulation.

The site of ancient Alesia is situated on Mont Auxois, above the present-day village of Alise-Sainte-Reine, in the département of Côte d’Or in the Burgundy district. Today, Vercingétorix is a near-mythic figure of Gallic nationalism in France. There is an enormous 7m tall monument on Mont Auxois, commissioned in 1865 by the Emperor Napoleon III from the sculptor Aimé Millet and the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who installed a nationalistic inscription on the base, attributed to Caesar: ‘A united Gaul forming a single nation animated by the same spirit can defy the universe’. Caesar, De Bello Gallico, VII.29

With the defeat of Vercingétorix, the subjugation of Gaul was complete. The Romans renamed the settlement Lutetia Parisiorum (Marsh of the Parisii), which evolved into Lutetia, and eventually Parisius, and named the river fluminis Sequanas (Seine).

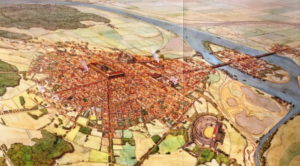

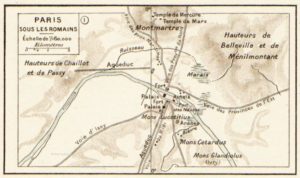

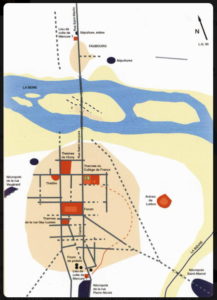

The Romans established a new settlement on a hill on the Left Bank of the Seine above the floodplain and marshes. With the typical grid plan of Roman towns of the time, they named it Mons Lucotitius, on what is now Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, between where the Panthéon is located, and further down the hill to the Luxembourg Gardens, where rue St. Jacques and rue Soufflot meet.

Rue St. Jacques is regarded as the oldest street in Paris. Planners probably first laid out two parallel roads (cardos) placed to take advantage of the shortest routes across the river and to avoid the marshy banks. The rue St. Jacques was the Cardo Maximum—north-south axis—of the Roman town, which extended all the way south to Spain, and north to Senlis. Over the river heading north, this road became what is now rue de la Cité and rue Saint Martin.

A second road, the present day rue Galande, then running into rue Mouffetard, came in from Italy via Lyon, Beauvais, Rouen and the Normandy coast. It was linked by the Decamani Maximii, which was a grid of perpendicular east-west roads, typical of all Roman planning. This grid plan remained at the core of Paris throughout the Middle Ages.

From 53 BCE to around 212 CE, the Romans built an arena, thermal baths, an aqueduct, a forum and houses—vestiges of which remain today—and just outside the town, an amphitheatre was built into a hillside. They also rebuilt the first wooden bridge over the Seine, originally constructed by the Parisii. The Petit Pont, as it’s now called, spans the small, narrow arm of the river between Île de la Cité and the Left Bank.

Lutetia was a fully-fledged Roman town by the 1st century CE. It was not the most important settlement in Roman Gaul, nor was it the most populous, having an estimated population of just under 10,000 residents. However, it was the political and administrative centre for the region and had all the buildings and public spaces typical of all provincial capitals, which prided themselves on being the image of Rome, the urbs par excellence.

The Romanisation of Paris was well underway by the early 1st century CE. There’s evidence for this from Le Pilier des Nautes, (Pillar of the Boatmen) an altar to Jupiter found in 1710 under the choir of Notre Dame Cathedral (itself built on the site of a Gallo-Roman temple), and regarded as the oldest extant Roman monument in Paris. Erected by a corporation of local river merchants and sailors (nautes), it invokes several Roman deities along with native Gallic gods. The sandstone pillar is now displayed in the frigidarium of the Musée de Cluny, (also known as the Musée National du Moyen Age).

Other temples and shrines from the Gallo-Roman period include a temple of Mercury on top of Montmartre, on or near the site of the Moulin de la Galette. Mercury was a popular god in Gaul, often syncretised with Gallic deities. The first bishop of Lutetia, Saint Denis, who became the patron saint of Paris, was martyred by the Romans in 250 CE by decapitation on the hill that would become Montmartre.

The saint was said to walk the streets of the city with his head in his hands. You can visit the Crypte du Martyrium de Saint Denis located at the base of Montmartre near metro Abesses.

A temple to the Egyptian goddess Isis, worshipped by many Romans including the Emperor Hadrian, was located in the Locutitius area of the Left Bank, that later became the St Germain-des-Prés neighbourhood.

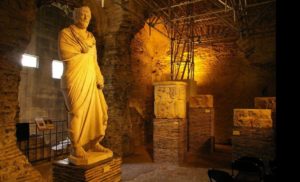

By far the most conspicuous Roman remains in Paris are the Thermae Lutetia (Thermal Baths) at the Musée de Cluny. Rediscovered in the 16th century, the baths are the preserved parts of a much larger spa complex of approx. 6,000 sq.m. that went from Bvd. St Germain to rue des Écoles, and from Bvd. St Michel to rue de Cluny.

The baths retain large sections of the frigidarium (cold rooms and pool), showing massive walls and barrel vaulted ceilings which rose to 14.50m, making it one of the tallest still visible in the Roman West. The complex provided a direct model for medieval architects building cathedrals, bridges and other large structures in the Romanesque style.

To appreciate the vastness of this whole grandiose complex, bear in mind that there were two levels unseen by the patrons: beneath the bath complex were the lower level of the water tanks, pipes and sewerage system, and an intermediate level for the staff and all the technical facilities.

Today, the frigidarium and the palaestra (gymnasium) are used as galleries in the museum. Included in these galleries are a number of Gallo-Roman sculptures and mosaics. Ruins of the caldarium (hot water room) and tepidarium (warm water room) can be seen from the street. Below-ground structures that have survived include a network of vaulted tunnels that supplied water, the sewer passages, as well as various service rooms. The remains of the caldarium have traces of decorated stucco adorning the walls.

Typical of all Roman bathhouses, there was a very social atmosphere. People came there not only to wash and have a massage but to relax, read in the library, perhaps have a haircut, talk business, or simply to meet friends. The spa complex also included an open-air palaestra designed for exercising, wrestling, weight-lifting and playing ball games. Rendez-vous at the baths for a catch-up and swap a bit of gossip, anyone?

The Musée de Cluny is open each day except Tuesday. A tour of the underground structures of the bath house is possible, but only with a guide. The tour takes about an hour, and there’s no need to book, although it’s available only at certain times of the day and on certain days. Check in advance at the Museum or the website: www.musee-moyenage.fr/en Note though that the museum is closed until 2022 for renovations.

The Cluny baths were fed by the subterranean aqueduct of Arcueil, with a source 16 km to the south at Rungis. This aqueduct was approx. 26 kms long and said to have had a flow rate of about 2,000 cubic metres per day.

In 1903-4 a second and third set of Roman baths came to light in Paris, one lying just south of the forum about 1 km south of the river, and another found in the 19th century in the College de France in the 5th arr.

Further excavations in 1993-4 at the College de France uncovered segments of plumbing and the water drainage system, as well as a multitude of ceramic and metal artefacts including lamps, fibulae (brooches or clasps) and key rings. These excavations confirmed that the baths once occupied an area of nearly 2 hectares. Archaeologists think that this was once the largest bathing complex in Lutetia.

The Arènes de Lutèce, located in the 5th arr., was a major centre of the city where people came to watch games, gladiatorial contests, plays and concerts. Constructed in the 1st century CE, it had a capacity of more than 15,000 people. It’s more typical of ancient Greek theatres rather than Roman ones, which were semi-circular. When Lutèce was sacked during the barbarian raids of 275 CE, some of the arena’s stonework was used to reinforce the city’s defences around the Île de la Cité. It later became a cemetery and was filled in completely following the construction of a wall in 1210. Over the ensuing centuries, the exact location of the arena was lost and only rediscovered during the demolition of the Couvent des Filles de Jésus-Christ in 1883. After a popular movement to restore it, championed by Victor Hugo, the Arènes de Lutèce reopened as a public space in 1896.

If you’re interested in visiting the Arènes, its address is: 49 rue Monge, 5th arr. It’s easy to miss the entrance, as it’s just a rather discreet arched walkway between a little brasserie and the small Hôtel des Arènes, on the left-hand side of the street coming up from Place Maubert/Bvd St Germain. As you’ve probably gathered, this is a small arena, so don’t go expecting to see another Arles or Orange arena, let alone a Coliseum!

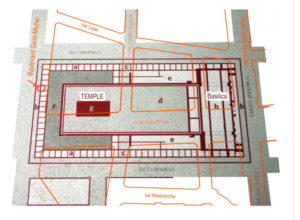

The Forum was the economic and religious centre of Lutetia, and was the emblem of Roman supremacy in the town. It was an impressive complex, 180m long by 90m wide, and covered the Bvd St Michel, rue de la Harpe, rue St. Jacques, rue Cujas and part of rue Soufflot. Its large, interior square would have been surrounded by a crytoporticus (gallery) of colonnaded porticoes decoratively concealing shops. A basilica was located in the eastern part of rue St Jacques, housing the financial, legal and administrative quarters of the city. Visitors would have entered the basilica through the current rue Victor Cousin.

A fragment of this complex was discovered in 1853 during the construction of rue Soufflot by the same archaeologist, Théodore Vacquer, who later excavated the Arènes de Lutèce in 1869. In the 1970s, during the construction of a post office on rue Cujas, more fragments—columns decorated with fluting, parts of the eastern wall and mouldings—were unearthed and are now on display in the Musée Carnavalet. Located in the Marais district, this fascinating museum is dedicated to the history of Paris and a must-visit for anyone interested in seeing over 600,000 works of art and artefacts from every era of the city’s development.

Another fascinating discovery of Roman ruins was made in the 1960s during excavations for an underground car park under the parvis (forecourt) of Notre Dame. The depth of the ruins indicates how much the city was built up over its history to protect it from flooding. Here you can see the well-preserved remains of a Roman house, public baths, a dock of the Roman port and more. The Crypte Archéologique de Notre-Dame is an intriguing and atmospheric time capsule that provides an insight into Roman Paris. While the focus is on the ancient history of Paris, the technology is resolutely modern, with interactive maps, touch screens and 3D animations. The Crypte is open every day throughout the year, except Mondays and entry costs around 8 €.

In May 2006 a Roman road and a city block were found during expansion works to the University of Pierre and Marie Curie in the 6th arr. The remains of private houses from the reign of the Emperor Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE) were recovered, including everyday items such as ceramics, bronze chains, flower pots and drawer handles. The original residents were wealthy enough to have their own private bath complexes as found in one of the houses, quite a status symbol among Roman citizens.

A Roman necropolis with Gallo-Roman and Merovingian tombs was located near the Petit Pont bridge, around the churches of St-Julien-le-Pauvre and St Séverin. Both these churches were built over tombs of Roman-era martyrs, evidence of the continuity between Late Roman and early medieval religion and burial customs.

At the Battle of Soissons in 486 CE, Clovis I, the King of the Franks, defeated the last Roman governor, becoming the ruler of Gaul. Clovis renamed the city of Lutetia to Paris, and made it his capital. He was also responsible for uniting the disparate Frankish tribes into one kingdom called Francia, and established the most powerful Christian kingdom in western Europe.

The history of Paris is a rich tapestry. When surrounded with so much beautiful architecture of more recent centuries, it’s easy to forget the city’s origins. But dig a little deeper, and it’s easy to find the archaeological and textual evidence of the ancient cultures that formed the modern City of Light.

Great history

Hi Sandy,

So glad you enjoyed it. Paris never ceases to surprise, does it? So many fascinating layers of history to delve into.

Cheers,

Cheryl