MUSÉE NISSIM DE CAMONDO – A MAGNIFICENT MANSION DEDICATED TO THE 18TH CENTURY

There are so many wonderful museums in Paris, selecting which ones to visit when you’ve got limited time is a challenge. We certainly have our favourites, and we also keep an eye on websites of Paris cultural institutions to check if there will be any special shows on during our next visit. One of our favourites since we first discovered it some years ago is the Musée Nissim de Camondo, which backs onto the beautiful Parc Monceau, and has a number of embassies and discreet 5-star hotels as its neighbours.

The Musée Nissim de Camondo houses a spectacular collection of French decorative art from the mid 18th century. These range from Aubusson tapestries, paintings by various renowned artists, Sèvres porcelain and fine furniture, through to items that once belonged to Marie-Antoinette.

The museum is a former hôtel particulier of great elegance and richness that records the sumptuous—but ultimately tragic—history of a highly successful family of bankers and philanthropists. The mansion was a re-build of the original constructed in 1863 for Nissim de Camondo, whose brother Abraham built his own mansion next-door, which is still there today. The new house was designed by a famous architect of the time, René Sergent, in 1911 for Count Moïse de Camondo, a banker, with the intention of setting off his collection of 18th century French furniture and objects dárt.

It was modelled on the Petit Trianon at Versailles, but with all the latest modern conveniences. On his death in 1935, it was announced that both the house and its magnificent collections were to be bequeathed to Les Arts Décoratifs in honour of his son, Nissim de Camondo, who was killed in WWI. The house opened as a museum in 1936.

The Camondo family had a fascinating history, although one perhaps not dissimilar to many other Sephardic Jewish people. The Camondos settled in several different Mediterranean countries, but particularly Italy, after being expelled from Spain in 1492, following a decree to Jews who refused conversion to Catholicism. Some members of the family became famous for their scholarship in Venice, others established themselves in Istanbul following the Austrian takeover of Venice in 1798, and thrived despite the many restrictions imposed on non-Muslims.

Two Camondo brothers, Isaac and Abraham, branched into finance in 1802 and founded their own bank, Isaac Camondo & Cie. Upon the death of Isaac, Abraham inherited the bank and also became the prime banker to the Ottoman Empire. As well as apartment buildings and a beautiful public stairway, known as the Camondo Steps in Galata, the Camondos built a sea-side mansion, popularly known as the Camondo Palace, on the northern shore of the Golden Horn.

The Camondos were often referred to as “the Rothschilds of the East,” although their citizenship was never Turkish. Since the late Ottoman period, the palace has been used as a headquarters by the Turkish Navy. Wanting to expand the family’s banking horizons, and in the wake of the Crimean War, Abraham’s grandsons settled in Paris in 1869, where they had already established business connections, and eventually transferred the bulk of their banking business there.

In recognition of his contributions and financial assistance to the liberation of the Venetian Republic from the Austrian Empire, Abraham Salomon Camondo was created a hereditary Count in 1870 by King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy—in the words of one cousin, a “flamboyant Italian title that sounded like that of a character in an Offenbach operetta.” Abraham died 3 years later in Paris. His grandson Moïse built the mansion in Paris that is now home to the museum. Unlike previous generations of the family, Moïse de Camondo was not greatly interested in business. Rather, he was drawn to art, and collecting works of art.

Moïse married Irene, the daughter of Jewish financier Louis Cahen d’Anvers, who headed a bank that eventually became BNP Paribas. She left Moïse in 1902 for the Italian stable manager at their estate, whom she married after she and Moïse divorced, and whom she then later divorced. She disappeared from his life forever, leaving him heartbroken and alone with their two children, Béatrice and Nissim.

Moise distracted himself by rebuilding the family mansion at rue de Monceau, and it became the focus as a gathering place for a blend of the financial aristocracy, Jewish aristocracy, well-known artists and writers, and the cream of upper class bourgeoise.

The latter included the renowned playwright Edmond Rostand (author of Cyrano de Bergerac), the celebrated author Marcel Pagnol (who wrote Jean de Florette), and the famous courtesan Genevieve Lantelme, whose involvement in a romantic triangle inspired Marcel Proust to write Recherche du Temps Perdu (‘In Search of Lost Time’). The acclaimed actress, Sarah Bernhardt, lived a few doors away and was a friend of the family. The novelist Emile Zola satirised this lavish compound as “a profusion, an explosion of riches”. Others described it as a “temple of gilded abundance.”

Moise was born in Istanbul in 1860. He went to live in Paris when he was a child, and grew up to become an avid Francophile. His main interest was the art of the 18th century that had been created shortly before the start of the Revolution: “the great century of the Enlightenment”. He devoted all his time and energy to acquiring works of the decorative arts from his favourite period, including rare glass objects from China that were all the rage during the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XlV.

One of his great acquisitions was silver dinnerware designed by the great silversmith of the age, Jacques Nicolas Roettiers, that had been commissioned by the Russian Empress Catherine the Great for her lover, Grigory Orlov (he was the leader of the 1762 coup which overthrew Catherine’s husband Peter III of Russia and installed Catherine as empress). All these artefacts were just a small part of the splendid treasures housed in his own Petit Trianon.

Methodical in his purchases and with a sense of symmetry in his home, Moïse often purchased items in pairs.

On 05 September 1917, Moïse de Camondo suffered another loss when his beloved son, Nissim, a combat pilot serving in the French Air Force, was shot down during WW1 somewhere over Lorraine, behind enemy lines. His body was not able to be recovered until after the war, and then was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery. Following this great tragedy, Moïse sunk into a deep depression and seldom left home.

At the same time, his obsession with collecting beautiful objects only intensified.

In an attempt to perhaps cling to what was familiar, he continued to collect a growing number of works of decorative art, including a rare porcelain dinner and tea service that had been manufactured at a factory in the city of Meissen, considered Europe’s first porcelain factory.

When he died in 1935, Moïse de Camondo wrote in his will that his lifelong project had focussed on glorifying French culture “in the period I loved more than any other.” He bequeathed both the house and its collections to Les Arts Décoratifs (now the Musée des Arts Décoratifs) in honour of his son, Nissim, in recognition of his ultimate sacrifice fighting for France in WWl. Moïse’s ex-wife, Irene, survived the war, with a new Italian surname, by escaping to a villa in the south of France.

Moïse appointed his daughter Béatrice to be the guardian over the rare artefacts and left her strict instructions. She was not permitted to loan out any works of art or add or acquire new ones. He even forbade her from moving any pieces of furniture or paintings from one place to another unless they remained in the same room, and left precise instructions about preventing the accumulation of dust.

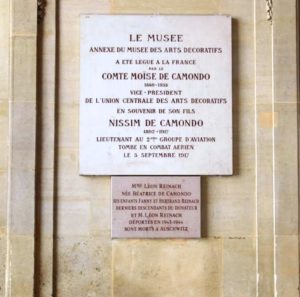

Around 1944 Béatrice, her ex-husband Léon Reinach, and their two children Fanny and Bertrand, were arrested, deported and on 04 January 1945 were murdered at Auschwitz, just 2 weeks before Soviet forces liberated the camp. In 1960, a small marble plaque was placed on the wall of the museum’s porte cochere commemorating this tragedy. This sits under a much grander one, placed there when the mansion opened as a museum in 1936, that commemorates the museum’s namesake, Nissim de Camondo. Indeed, it could be said that the museum is a legacy of beauty and remembrance.

Today, the mansion is maintained as if it were still a private home preserved in its original condition. Three floors are open to visitors: the lower ground floor that has the kitchens; the upper ground floor that has formal reception rooms; and the first floor with the private apartments. As well as the gardens, there are also the outbuildings built in 1863, and later enlarged by Moïse’s father, Comte Nissim de Camondo, and modified again by Moïse.

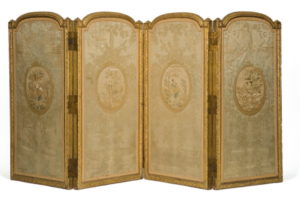

Antique timber panelling provides a backdrop for the creations of the cabinetmakers and carpenters who supplied the Royal Furniture Repository with luxurious, finely crafted furniture. There are a few precious items from the Rococo period, such as a pair of lacquer corner cupboards with gilt bronze mounts, but the majority of pieces are from the reign of Louis XVI, for example the folding screen made in 1785 for Louis XVI’s games’ room at Versailles.

Complementing the furniture, a number of mantel and wall clocks, barometers, chandeliers, wall lights and vases with gilt mounts add sparkle to the timber panelling and furnishings. There are a number of pieces from Marie Antoinette’s collection at Versailles, including a set of furniture by the iconic furniture maker Georges Jacob, a chiffonier (sewing table) and a desk created by the master cabinetmaker Jean-François Oeben, the Queen’s furniture-maker of choice.

The walls and floors are decorated with exquisite carpets and tapestries produced by the Gobelins, Beauvais and Aubusson factories. As well as the silver pieces from the Orlov service commissioned by Catherine the Great, there is a famous Sèvres porcelain service known as the “Buffon”, produced in the 1780s, each piece of which is decorated with a different bird, copied from lithograph plates in the Comte de Buffon’s ‘Natural History of Birds’.

The paintings and sculptures reflect the taste of their collector, notably views of Venice by Francesco Guardi, portraits by Vigée-LeBrun and Francois-Hubert Drouais, landscapes by Hubert Robert and an exceptional series of sketches by Jean-Baptiste Oudry as cartoons for the “Royal Hunts of Louis XV” tapestries.

Although Comte Moïse de Camondo wanted to re-create an 18th century residence, the mansion was surprisingly modern. It was fitted with all the latest conveniences in terms of efficient service and everyday comfort: a heating system with warm, filtered air, compressed air elevators, a vacuum cleaning system; cove lighting; hygienic bathrooms, and even nine porcelain “water closets” with a flush-valve system. The house’s archives provide details of all the original work, and also about the changes made over the 20 year period until the Comte’s death in 1935.

Although the façades of the new mansion were inspired by the Petit Trianon and the apartments panelled with 18th century timber wainscotting, Sergent’s design satisfied the requirements of private dwellings in the late 19th century by separating public and private life and domestic service.

The architect, René Sergent, kept the courtyard and garden layout of the former mansion. He reorganised the original outbuildings into stables on one side for the horses, while on the other, an outhouse where horse-drawn carriages used to be kept was converted into a garage for cars, with a repair workshop and apartments for the chauffeur and mechanics.

A recent renovation of the outbuildings has seen the former garage transformed into a beautiful new restaurant, Le Camondo. It has retained its coffered ceiling and metallic columns that made up the structure of the space, and opens onto a paved courtyard that’s protected from external noise, just like a secret garden, that’s perfect for lunches and dinners on warm days. This warm and inviting space boasts a cosy atmosphere featuring an interior design that mixes styles and materials with the spirit of an elegant conservatory, echoing the feeling of a private club.

At the helm of the kitchen, a young chef, Alexis le Tadic, has created a lively and interesting menu, offering updated classics as well as some Italian dishes and those with a more exotic origin. The chef hails from some very prestigious kitchens, including Alain Ducasse’s ‘Louis XV’ in Monaco, ‘Jouvence’ that was awarded a Bib Gourmand Michelin bistro designation in 2017, and ‘Le Comptoir’, both of which are in Paris. In addition, Le Camondo’s world pastry champion Christophe Michalak, has created some delicious treats to indulge in.

Musée Nissim de Camondo is located at 63 rue de Monceau in the 8th arr. Opening hours are Wednesday – Sunday. Restaurant Le Camondo’s address is next door at no. 61 bis, and is open Monday – Saturday.

One interesting bit of trivia is that the Museum was used as a film location for the hugely enjoyable French series ‘Lupin’ on Netflix, starring the charismatic Omar Sy as the charming Assane Diop—based on the famous French literary character Arsène Lupin, gentleman thief. If you’ve managed to catch the 5 episodes of this intelligent, exciting series, you may have observed that the mansion was used as the home of the character Hubert Pellegrini. Catch it if you can.

This is SO INTERESTING, Cheryl. I LOVE your blogs . Thanks again .

Cheers, Lois

Hi Lois,

Thank you so much for your warm words of praise. I’m so delighted you enjoy the blogs, and that’s exactly why I do them! Graham and I returned from 5 weeks in France last night and I’ll have more to say about that shortly. So many wonderful new things to see, and so cheering to see how everything has pretty much returned to normal, not only in Paris, but the countryside.

Cheers, Cheryl