L’HÔTEL DE LA MARINE – A TOUCH OF VERSAILLES IN THE HEART OF PARIS

If you’ve been to Paris more than once, very likely you have been past the Hôtel de la Marine. This is not a hotel in which you stay, but a hôtel particulier of epic proportions. A “real” hotel, the historic, luxury Hôtel de Crillon, is adjacent. These opulent 18th century buildings are a perfectly balanced pair facing onto Place de la Concorde. Fortunately, during its long and illustrious life, from the reign of Louis XV through the centuries housing the Navy Ministry offices, it has never sustained damage or serious changes that would have compromised its presentation of fine French craftsmanship and as an expression of power.

The Place de la Concorde was originally named Place Louis XV, as the city fathers of Paris wished to erect a statue of the king and place it in a square to honour the king and celebrate his recovery from a serious illness. It would be an equestrian sculpture portraying the monarch as a heroic Roman emperor. After a period of indecision, the King decided on some swampy land belonging to him between the gates of the Jardins des Tuileries and the Champs Elysees.

An architectural competition was launched for the development of the square, and 19 proposals were put forward, but none satisfied the King. After 5 years of debate, the King’s chief architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel, created the definitive plans for the future square, Place Louis XV, by fusing the best ideas from the different project ideas, and would include two new identical palaces which symmetrically face onto the square, although their specific uses weren’t defined at that stage. The most distinctive feature Gabriel borrowed was the neo-classical façade of columns facing the square, which were largely inspired by the Louvre colonnade designed by Claude Perrault in 1667-74.

The three storey frontage of each palace is decorated with sculpted medallions and garlands, another feature borrowed from the Louvre. Each main façade is balanced at either end by two sections with pediments and Corinthian columns. The distinctive central feature of the façade, that differs from the Louvre, is the two storey loggia, or verandah, which is decorated with sculpted octagonal medallions on the ceiling, representing the benefits the King was said to bring to the nation. There are also allegorical symbols of music, the arts, industry, agriculture, defence, and commerce. The King’s monogram was also included, but these were smashed during the Revolution.

Once the plans had been drawn up and development work on the square finally got underway in 1758, it was time to find a role for the two new palaces on the north side of the square. To the west of rue Royale are four separate buildings disguised behind a single façade, which became residences of the nobility. Today, number 10 is the Hotel de Crillon, and the Automobile Club of France occupies nos. 6 and 8.

In 1768 the decision was made to house the institution in charge of the King’s furniture, the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne, (furniture storage of the Crown) in the eastern palace, between today’s rue Royale and rue Saint-Florentin, the future Hôtel de la Marine.

This institution was the forebear of the Mobilier National, today’s public body for managing France’s state-owned furniture. At first, the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne was supposed to occupy only part of the building, but by the end of 1767, it ended up filling the entire edifice. The origins of the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne go back to the Middle Ages when the king and his court led a somewhat nomadic lifestyle. The travelling court would go from one royal residence to another. These residences therefore had to be fitted out as and when the royal court travelled. The courtiers charged with dealing with all this were the ‘room valet and steward for the king’s rooms and carpets’ who had to ensure that each the royal residence was suitably furnished before the forthcoming arrival of the king and the rest of the courtiers.

It goes without saying that this institution was abolished during the Revolution. In 1800, it was reborn as the Garde-Meuble des Consuls, but when Napoleon Bonaparte became emperor, it was renamed the Mobilier Impérial in 1804. The new emperor also created a detailed inventory system that was strictly audited on a regular basis to ensure that courtiers didn’t help themselves to items in the collection to furnish their own residences, which apparently had been quite a common occurrence in the past.

Even during the reign of Louis XV, the fine furniture and tapestries held at the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne were considered National, not personal property. In 1772, the Garde-Meuble became the first museum of decorative arts in Paris, and its galleries were open to the public on the first Tuesday of each month between Easter and La Toussaint (All Saints’ Day), 01 November.

The Garde-Meuble contained a chapel, a library, workshops, stables, and apartments, including those of the Intendant of the Garde-Meuble, a member of the highest level of the King’s court. The last official to hold this post was Marc-Antoine Thierry de Ville-d’Avray (1784-1792), and it’s the apartment from his time that has been restored and is now on display. Marie-Antoinette also had an apartment there which she used when visiting Paris from Versailles.

The Intendant’s apartments are located on the eastern side of the first floor, which today have a view over Place e la Concorde and rue Saint-Florentin. The apartments exemplified what was perceived as the ideal apartment at the end of the century of Enlightenment, that included at least an antechamber, a bedroom and a small private room. A bathroom was added later. The bedroom of Madame Thierry de Ville d’Avray is on the south side. The two apartments are linked by the salon and dining room. A mirrors room and the golden room were also installed by the Intendant.

During the 18th century, aristocratic society held receptions almost daily. The mistress of the house would host these lavish parties, welcoming leading Parisian figures and intellectuals. Hosting such occasions was an art form, which can be seen in the way the apartment’s rooms were arranged and in the splendour of the reception rooms. The monumental staircase played a central role in impressing important guests as well as providing a route to the exhibition galleries on the first floor. The grand gallery hosted many impressive receptions, as well as balls for the coronations of Napoleon and King Charles X.

By 1789, the Garde-Meuble also held a large collection of weapons, mostly ceremonial, including swords, medieval lances and two ornate cannon, which Louis XIV had received as gifts from the King of Siam. On 13 July 1789, a large crowd, angry at the King’s decision to dismiss his finance minister Jacques Necker, marched to the building, urged on by the radical orator Camille Desmoulins. Thierry de Ville-d’Array happened to be away that day, and his deputy was terrified by the angry mob. To appease them, he invited the crowd inside to take away the weapons and two cannon, but pleaded with them to spare the artworks, tapestries, and fine furniture. The next morning, 14 July 1789, the two cannons fired the first shots at the Bastille, the act that launched the Revolution.

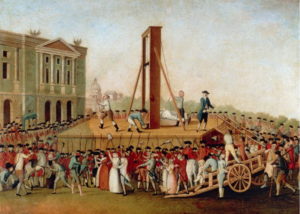

In October, the Secretary of State for the Navy, Cesar Henri de la Luzerne, moved his offices to the Garde-Meuble, and from then on it housed the naval ministry. The Navy gradually expanded its offices, and by 1798 the navy occupied the whole building. In 1792 a remarkable crime took place within its walls. A set of diamonds used in the coronation crowns of Louis XV and XVI, including the famous Regent Diamond, had been moved to the building for safekeeping. On the night of 16-17 September 1792, the diamonds disappeared. The thieves were later caught and guillotined in front of the building. These were the first executions by guillotine on the Place de la Concorde. The diamonds were also recovered, discovered in an attic in Paris.

In 1793, during the Reign of Terror, the portion of the Place de la Concorde in front of the neighbouring building, the Palais de Gabriel (now the Hôtel de Crillon), was the site of the guillotine, and the place of execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, and in 1794, of the leaders of the Revolution, Danton and Robespierre. With the fall of the monarchy, the Place Louis XV had a name change to Place de la Révolution, then finally to Place de la Concorde from 1795.

Throughout the 19th century, the building was modified for the various needs of the Navy. New wings were constructed behind the original building, and a neighbouring building in rue Saint-Florentin was purchased in 1855 and added to the Hôtel. The interiors also had some changes, such as the large hall used for the display of large pieces of royal furniture was replaced by two new salons honouring great moments in French naval history. However, the grands salons and the Galerie Dorée still remained.

From its vantage point, the building bore witness to pivotal events in French history, and was the scene of several historic events, from a ball honouring the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804, the celebration of dedication of the 3,000 year old Luxor obelisk—the erection of which was a pharaonic task in itself—on the Place de la Concorde by King Louis Philippe in 1836, and the drafting of the decree of the French President abolishing slavery in April 1848.

After the fall of France in June 1940, the Kriegsmarine, the naval forces of Nazi Germany, set up their headquarters there. They remained until they had to evacuate due to the oncoming of American and Free French forces in August 1944 and the building itself was one of the symbolic locations for the city’s liberation celebrations. In 1989 President Francois Mitterrand invited foreign leaders to the loggia of the Hôtel to view the parade celebrating the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution.

In 2015, the French government decided to consolidate all of the French military headquarters at a single site, the so-called Hexagon at Ballard in the 15th arr., and the navy left the Hôtel de la Marine. The decision was made to keep the building as a public monument under the direction of the Centre Monuments Nationaux (CMN).

The restoration took more than four years, to the tune of €132 million, and involved more than 1,000 specialists in 50 different trades, including gilders, upholsterers, smiths, and carpenters. “It was like an archaeological excavation,” explained Jocelyn Bouraly the National Monuments’ administrator. It’s an immersion into Versailles-style opulence, and many say it boasts the most beautiful balcony in Paris, offering some of the best views of the city.

The most dazzling room is the Galerie Dorée, and it beggars belief to learn that it had been covered with stainless steel walls during its incarnation as a kitchen in the 20th century. When these steel panels were removed the restorers discovered 18th century decorative boiserie was miraculously preserved. Scrupulous detective work allowed CMN experts to track down a set of furniture that used to adorn the room when it was the Intendant’s personal study, including a secretaire and the exquisite Table of the Muses—both designed by Jan Henri Riesener, Marie Antoinette’s favourite ébéniste.

Another showstopper is the Cabinet des Glaces a mirror-walled boudoir covered in paintings. “We’ve sought an identical restitution of these rooms so that when visitors enter, they have the feeling that the residents left just an instant before,” says Bouraly.

The table in the dining room is dressed as it would have appeared at the end of a decadent dinner, the silk wall hangings were painted by hand, based on archival records.

Visitors enter the complex from rue Royale opposite Restaurant Maxim’s, into a courtyard where the cobblestones are paved with a carpet of embedded LED lights while the smaller, adjacent courtyard that forms the main visitor entry is topped with a head-pivoting glass canopy that refracts the light.

There are no signs in the museum, except to point you in the right direction, no little descriptions next to the artworks, no printed panels or signs to read as you enter each room.

Instead, the visitor is issued with a headset called “Le Confidant”, in which a historical character guides you through the visit with little stories and descriptions of each room. It has been designed as “a theatrical voyage in time”, according to the architect who conceived the scenography. “We wanted to create real scenes with characters to give an emotional component to the visit, not just imparting the historical information you can find in books.”

However, we found that there were a few blips with the timing of the commentary, which was somewhat out of synch with our walking pace, and needed some adjusting. Perhaps this was due to us being early visitors to the building, and by now such issues have been dealt with.

In the former tapestry storerooms, an impressive private art collection has also opened. The Al Thani Collection, featuring artworks spanning more than 5,000 years from numerous civilisations, including ancient Egypt, China’s Han Dynasty, and the Mughal Empire, are on show. At the time of our visit, the entry fee to the monument did not include this exhibition.

The Hôtel de la Marine is open every day from 10.30hrs to 19.00hrs, but closes later on Fridays at 21.30hrs. There are two ticket prices to choose from: the “Reception Room and Loggia” (45 mins.) for €13 or the “Grand Tour” which includes the 18th century apartments (90 mins.), for €17.

It’s absolutely worth it to pay the extra for the “Grand Tour”, as this offers so much more—we saw no point in choosing the cheaper, shorter duration! Whichever you choose will be loaded into your “Confidant”. Note too that at the time of our visit, there was not a coat-check/storage facility, and large bags can’t be brought into the museum. Hopefully, this shortcoming will be dealt with soon. Book tickets before you go, as numbers are limited each day.

After your visit, you can browse through the Hôtel de la Marine’s boutique that’s been fashioned as a cool concept store, or head to the Café Lapérouse, which offers all day dining in the courtyard.

On the opposite side of the courtyard there is the very upmarket restaurant, Mimosa, headed by one of France’s leading chefs, Jean-François Piège.

The Hotel de la Marine is a magnificent addition to the huge selection of museums and sights to see in Paris, and if you don’t have time to head out to Versailles, this will give you a small taste of that without leaving the city.

Thanks again, Cheryl. And yes , I have gone past it lots of times, when I was staying in a rather poxy little hotel in the Rue de Richelieu . Lois .

Hi Lois,

I know what you mean about going past it and not quite knowing what went on inside. We had the same experience for years, other than knowing, in a very general way, that it was the headquarters of the French Navy, we’d no idea what lurked within! It’s quite dazzling, and we can highly recommend it for a few hrs.

Regards, Cheryl