DISCOVER THE BEAUTIFUL MUSÉE RODIN IN PARIS

Without doubt, the Musée Rodin is one of the loveliest museums in Paris. This has as much to do with the beautiful garden as the fabulous collection itself. We first visited this museum back in the ‘70s, and revisit it as often as we can. It’s located in rue de Varenne, just a few minutes’ walk from the Invalides and the Eiffel Tower, in a very swanky part of the 7th arrondissement, with embassies as neighbours, and discreet mansions with high walls that shield them from the admiring gaze from passersby.

The museum is housed in a very fine Parisian mansion (hôtel particulier), the Hôtel Biron, built in 1727 by the architect Jean Aubert, and stands amidst a beautiful garden, the whole site occupying some 3 hectares. The mansion takes its name from the Duc du Biron, who became a distinguished military leader. He bought the mansion in 1753. Previously, it had belonged to Louise Bénédicte de Bourbon, the beautiful daughter-in-law of Louis XlV.

From the late 18th century, the house passed through numerous hands, becoming at various times the seat of the papal legate, the official residence of the Russian ambassador and a boarding school for girls. Stripped of its furnishings and falling into disrepair, the house was used as a boarding house for poor artists, poets and performers. Among them at various times were Henri Matisse, Jean Cocteau and Isadora Duncan.

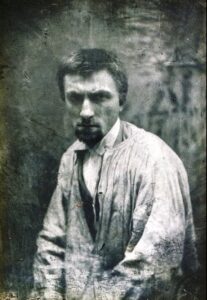

Rodin was born into a poor family. At the age of 13, he entered a drawing school, where he learned drawing and modelling in various materials. At 17 he attempted to enter the École des Beaux-Arts, but although he passed the drawing competition, it’s hard to believe, but he failed the very competitive sculpture competition three times. Art experts tend to agree that Rodin’s naturalistic artistic style simply did not fit with the school’s conservative academic approach. In 1858 a dejected Rodin decided to earn his living by employment in plaster workshops, creating architectural ornaments and doing decorative stonework.

By 1864 he had begun to work with the sculptor Albert Carrier-Belleuse and in that year made his first submission to the official Salon exhibition, ‘The Man With the Broken Nose’ was rejected. He completed various independent works, and in 1871, he went with Carrier-Belleuse to work on decorations for public monuments in Brussels following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, during which he served as an officer. However, he was dismissed by Carrier-Belleuse, so then collaborated on the execution of decorative bronzes with other sculptors.

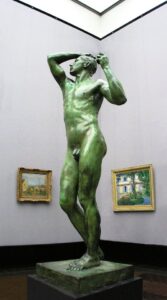

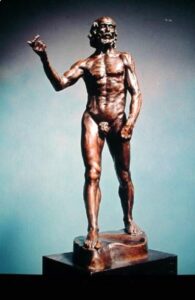

In 1875, he took a trip to Italy, and what he saw on this visit gave him the artistic shock that stimulated his genius. He visited Genoa, Florence, Rome, Naples and Venice before returning to Brussels. The inspiration of Michelangelo and Donatello rescued him from falling under the influence of the academic establishment. One particular work from this time, the bronze ‘The Vanquished’, regarded as his first truly original work, provoked scandals in the artistic circles of Brussels and again at the Paris Salon, where it was exhibited in 1877 as ‘The Age of Bronze’. People were shocked at the realism of the work, and his contemporaries accused him of having formed its mould upon a living person.

These false charges caused Rodin great distress, but nowadays it’s acknowledged that the figure’s musculature was rendered with such subtlety and skill that it was a testament to Rodin’s sublime talent. He was able to disprove the accusations with photos taken in his workshop at the time he was creating the work. Eventually, a group of prominent artists signed a letter of support for Rodin which they presented to the French government, and ultimately, the French state bought ‘The Age of Bronze’, had it cast in bronze and placed in the Luxembourg Gardens—the authorities were too afraid of the severe criticism the work still aroused to display the sculpture in the main Luxembourg Museum.

Rodin returned to Paris in 1877 and two years later, his former master Carrier-Belleuse, now director of the Sèvres porcelain factory, asked him for designs. He was rejected in various competitions for monuments to be erected in London and Paris, but finally received a commission to execute a statue for the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. His ‘St John the Baptist Preaching’ of 1880 was a success and this work, as well as ‘The Age of Bronze’, at the salons of Paris and Brussels in that year, finally established his reputation as a sculptor at the age of 40. At an age when most artists already had completed a large body of work, Rodin was just beginning to affirm his personal artistic style.

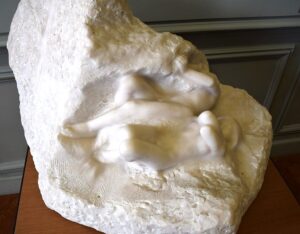

He received a commission to create a bronze door for the future Musée des Arts Decoratifs, a grant that provided him with two workshops, and whose advance payments at last made him financially secure. This commission was meant to be delivered in 1884, and although Rodin worked on it intensely for several years, he still failed to complete it for the 1889 Exposition Universelle. It was still left unfinished by the time of his death in 1917. The theme of its scenes was taken from Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’ but eventually it came to be called ‘The Gates of Hell’. It’s thought that his concept for this work was inspired by Ghiberti’s ‘The Gates of Paradise’ doors of the Baptistery in Florence. His failing health and the outbreak of WWl put an end to his plans to carve the work in marble.

At the time of his death, ‘The Gates of Hell’ stood in Rodin’s studio like a gigantic plaster chessboard with all the pieces removed and scattered around the floor. The arrangement of the figures on ‘The Gates’ as we now know it, reflects the arrangement documented by numbers pencilled on the plasters which corresponds to numbers located at various points on ‘The Gates’. However, it’s generally acknowledged that as Rodin frequently changed these numbers and played around with the surface of the doors, ‘The Gates’ are regarded as very much unfinished at the time of his death.

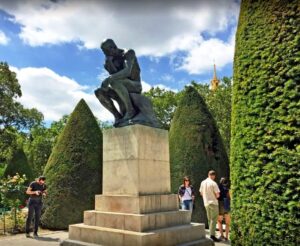

Although Rodin did not complete ‘The Gates of Hell’ during his lifetime, his work on this project did inspire him to create other individual works. ‘The Thinker’ (Le Penseur) is perhaps the most famous example of these. It’s thought that when he created this work Rodin was inspired by Michelangelo’s ‘Il Pensieroso’ which he saw in Florence.

Both ‘The Gates of Hell’ and ‘The Thinker’ are in the garden of the Musée Rodin, along with numerous other works by Rodin such as ‘The Monument to the Burghers of Calais’ and ‘Ugolino and His Sons’, ‘Orpheus’ and the ‘Monument to Balzac’. Rodin displayed his sculptures in the garden during his lifetime, and the Musee Rodin has continued this tradition, allowing visitors to see how the sculptures interact with their natural surroundings, just as Rodin intended. As well as these famous masterpieces, there are 30 bronzes placed throughout the garden.

Following Rodin’s wishes, the sculpture garden at the Musée has been designed to show the harmony between nature and sculpture. As the various trees and flowers change with the seasons, he thought that this natural setting showed the sculptures to their best advantage. If you visit during warmer months, a bench in the garden under the deep shade of the trees is an ideal spot for enjoying a moment of calm and contemplation.

There are flowers in bloom all year round in the sculpture garden. After the Christmas roses in winter, the pink viburnum blossoms attract the first bees. Each month has its own dazzling blooms, and especially in May, when the abundance of roses makes the garden a riot of bright colour, complemented by the delicate colours of the hydrangeas, and the scent of lime trees fill the garden in the summer. During September, the leaves on the trees turn to gold.

Inside the museum itself, it’s set out in chronological order, so starting on the ground floor, begin your tour by turning left as you enter. Room one is devoted to Rodin’s beginnings, followed by his early career, and so forth, through to room eight, where you come to his emergence as a sculptor, his artistic circle, ‘The Gates of Hell’, the various public monuments, his fame, and then his life at the Hôtel Biron. Upstairs, your tour takes you through rooms 11 to 18, called respectively Hugo & Balzac, Rodin & Carriere, The Art of Portraiture, Monet & van Gogh, 1900 Rodin’s Glory, Assemblage & Variation, Enlargement & Fragmentation, Camille Claudel, Rodin & Antiquity, and finally, Towards the 20th Century.

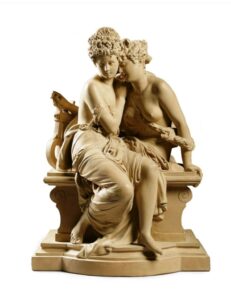

The room devoted to Camille Claudel deserves a special mention. Around 1884, Rodin, who had had many lovers outside his relationship with Rose Beuret, became seriously romantically involved with the figurative sculptor Camille Claudel, who joined his studio that year as an assistant. Rodin was a great admirer of Camille’s natural beauty and considerable talent, and within a year, they were engrossed in a tempestuous affair that lasted until 1892, though they continued to see each other until 1898. During their relationship, they modelled portraits of each other, and she assisted Rodin on a number of his works, as he did for her.

Camille eventually separated from Rodin when he refused to end his relationship with Rose Beuret, despite having signed a contract in October 1886 promising to do so and marry her. By the time Rodin’s ‘The Kiss’ was presented at the 1898 Salon, their torrid affair had ended. Camille’s intense jealously of Rose had developed into symptoms of paranoia and rage, and her subsequent and serious decline in mental health is well documented. In March 1913, she was committed to a mental hospital where she stayed until her death in 1943. Tragically, during this time she destroyed many of her sculptures and drawings.

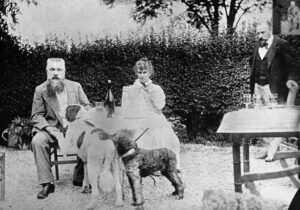

In 1908 Auguste Rodin rented 4 of the ground floor rooms in the Hôtel Biron that became his studio while he continued to live at the Villa des Brillants at Meudon in the Hautes-de-Seine with his lifelong partner, Rose Beuret, a seamstress and laundress. She stood by him despite his numerous sexual relationships with numerous other women, and the fact that they had a son, Auguste-Eugene Beuret, whom Rodin never recognised publicly.

In 1911, the State evicted the artists, and the mansion was listed for demolition. Rodin battled to save the building, and the key to his success in doing so was his promise that he would leave his entire estate to the French state on condition that his art must be housed at the Hôtel Biron. In 1916, when Rodin donated his lifeworks including copyrights to the State, he created the only French national museum that is the legal successor of an artist. Sadly, Rodin didn’t live to see his museum realised. The Musée Rodin opened in 1919, 2 years after his death. Today, it’s home to more than 32,000 items, including 6,788 sculptures, 9,000 drawings as well as Rodin’s own vast collection.

The Hôtel Biron closed in 2012 for an extensive renovation to the tune of €16 million, reopening on 12 November in 2015, on what would have been Rodin’s 175th birthday. During the 3 years of this project, Rodin’s works were restored, and his remarkable personal collection of paintings and antiques were added to the museum’s collection. These include works by Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, John Singer Sargent, Edvard Munch, Vincent Van Gogh and artefacts, objects and ceramics from Italy, Greece, Egypt and the Middle East, plus thousands of photographs.

The former rather harsh white walls were repainted in a soothing colour palette, created especially for the museum, which Farow & Ball Paints called Biron Grey, as a perfect tone to highlight the artwork. It was during these works that the chronological order of Rodin’s life was set out across the 18 rooms, which is what we see today. The room called ‘Rodin at the Hôtel Biron’ shows the space exactly as it was when he lived there, including the original furniture. The overall effect feels more like a peaceful country château than a Paris museum.

It’s often suggested that the best way to visit the Hôtel Biron and its garden is to start with the interior, and then explore the garden, which covers over 3 hectares, and we think that’s definitely the best option. The perfect way to relax afterwards is to head to the delightful, newly renovated café called L’Augustine tucked away in the heart of the garden, which opened in 2020. It offers indoor and outdoor seating, a contemporary menu featuring seasonal dishes and sweet treats from Maison Lenôtre, as well as a great selection of ice creams.

The Musée Rodin is located at 77 rue de Varenne in the 7th arr. and the nearest metro is Varenne on Line 13. The museum is open Tues. – Sun. 10.00am – 5.45pm. Entry fee is €14. Note that like many museums in Paris, entry is free for everyone on the first Sunday of the month, from October to March. No need to book in advance.

If you enjoy your visit to Musée Rodin and would love to see more works by Rodin, consider a trip out of Paris to visit his Villa des Brillants at Meudon in the Hauts-de-Seine. In total, the museum holds an astonishing 6,600 sculptures, 8,000 photographs and a similar number of drawings, as well as some 7,000 objects d’art. To get there, take a train from Line C RER, (say from Gare Austerlitz, St Michel or Musee d’Orsay—check your metro map) in the direction of St Quentin-en-Yvelines, and get off at Meudon-Val-Fleury RER stop, then a short walk of about 1km along rue Henri Barbusse which runs into Ave. Paul Bert, cross the railway, where the road has become Ave. Auguste Rodin. The address is 19 Ave. Auguste Rodin. Despite some online info. saying the Villa is open Mon-Fri., we discovered that it is open only on Saturdays, from 1.00pm – 6.00pm.

A particularly interesting episode Cheryl.

Hi Nadine,

It’s a particular favourite museum for us. Not just the wonderful artworks, but the gorgeous gardens. A tranquil haven indeed. Cheers, Cheryl