MUSEE GUIMET – 5,000 YEARS OF ASIAN ART IN PARIS

When we think of museums in Paris, what immediately springs to mind are the internationally famous institutions such as the Louvre, Quai d’Orsay, Pompidou Centre, and perhaps the recent addition of the Fondation Louis Vuitton. But Paris also has the largest and most important collection of Asian artefacts in Europe at the Musée des Art Asiatiques Guimet in the 16th arrondissement. From the Buddhas of Afghanistan, the Zen monks of Japan, Samurai armour, Indian fabrics, to fine Chinese art and Khmer treasures, the Musée Guimet offers a unique opportunity to take a meditative, aesthetic journey to discover the heart of Asian art and culture.

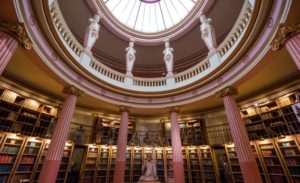

The Musée Guimet describes itself as “illustrating the diverse cultures and civilisations of Asia, covering an area as vast in time (five millennia) as in space (from India to Japan)”. From the moment you enter and are greeted by a vast hall of statues (many from Cambodia) under the library dome, you never forget that this is a museum of Asian Art.

With around 45,000 objects from the neolithic period onwards, the collections are beautiful, and the quality and variety of objects are impressive. Statues of the Buddha, Amida and Shiva share space with calligraphy, sumi paintings and decorative arts. They are divided into areas so that you can compare and contrast the art of Afghanistan/Pakistan, the Himalayas (the Guimet has one of the finest collections of Himalayan art in the Western world), with that of Southeast Asia, Central Asia, China, Korea, India and Japan, and look through the collection of historic photographs and treasures of the Library, which include works on Asian religion and philosophy as well as art.

The original collection—hundreds of Japanese artworks and Chinese artefacts—was put together by one man, Émile Guimet. A wealthy industrialist from Lyon, Guimet (1836–1918) dedicated his life to travel and adventure. In the 19th century, he was commissioned by the French government to study the religions of Asia. His idea was to devote a museum to the religions of Asia, Ancient Egypt and Antiquity.

Guimet’s travels around the world in 1876 took him to Japan, China and India. On his journey along the Silk Road, he acquired an extensive collection Asian art and artefacts. As well as historical objects, he was also very interested in contemporary objets d’art. Originally, his collection was housed in a museum in his hometown of Lyon, but it was moved to Paris in 1889—the same year that the Eiffel Tower was inaugurated.

During Guimet’s lifetime, the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet (its official name) shifted focus from the religions of Ancient Egypt to the art of Asian civilisations. Other archaeologists, inspired by Guimet, visited Siam (as Thailand was then known) and Cambodia, studying the cultures and gathering additional collections to bolster the burgeoning museum. Guimet donated his vast collection to France in 1884. In 1945 the collections of Oriental art in the Louvre were transferred to the Guimet, and it was established as the Department of Asiatic Arts of the Musée du Louvre. In exchange, the Musée Guimet sent its collection of Egyptian artefacts to the Musée du Louvre, where it’s still on show today.

In 1891, when the museum was still largely dedicated to religions, Émile Guimet organised Buddhist ceremonies there: Georges Clemenceau, who attended, was one of the Parisians who discovered this spirituality without leaving the capital. In 1905, Guimet invited a dancer of Dutch origin to the museum who astonished all of Paris with her “’orientalised” and erotic interpretations of Brahmanic dances. It’s said that following her sinuous passage between the columns encircling the library rotunda that her stage name came to her. Henceforth, she was known as Mata Hari.

Over the years, the museum has decreased the number of religious relics in order to showcase other treasures from Asia, starting in 1912, when religious icons were replaced with Tibetan art collections. In 1927 the Musée Guimet was placed under the management of the French Museums Directorate, and it was in this period of colonial occupation that large collections from Central Asia and China were added.

Since then, the collections have continued to grow and diversify, while maintaining the curiosity and appreciation of Asian art and Asia’s capacity for adaptation and innovation through the centuries. In 1927, the collections increased thanks to the donations of Paul Pelliot and Edouard de Chavannes from their expeditions to Central Asia and China, as well as the original artefacts collected by Louis Delaport that formed the core of the Trocadéro’s Indochinese Museum. In 1965 the museum paid particular attention to enriching the collections in the field of classical India.

The Musée Guimet has acted as a safe haven for artworks and artefacts during wars and conflicts. From December 2006 until April 2007, it harboured collections from the National Museum of Afghanistan, also known as the Kabul Museum, with archaeological pieces from the Greco-Bactrian city of Ai-Khanoum, and the Indo-Scythian treasure of Tillia Tepe. Usually referred to as the Bactrian gold hoard, this comprised about 20,600 ornaments, including an astonishing gold crown and exquisite jewellery, coins and other objects made of gold, silver, and ivory.

When the Afghanistan civil war started in 1992, the museum in Kabul was looted numerous times and destroyed by rockets, resulting in the loss of 70% of the 100,000 objects on display. Other institutions, including museums in Germany and the U.K. also managed to rescue many objects. Since 2007, these organisations have helped recover over 8,000 stolen works, and together with the objects in their care, repatriated them back to Afghanistan. Unfortunately, it’s not known what has become of the objects in the National Museum of Afghanistan since the recent return of the Taliban.

The vast renovation program that started in 1996 gave the Guimet access to the technological advancements of museology in terms of display and conservation of art objects. The origins of this program started back in 1991 when the museum moved into an adjacent building, called the Buddhist Pantheon, to enable a larger redevelopment to be implemented. The main aim was for the institution to assert itself more and more as a major centre of knowledge of Asian civilisations in the heart of Europe.

Priority was also given to increasing the amount of daylight and the creation of open perspectives in the permanent galleries. These larger spaces allow visitors to better understand the relationships and differences between the various artistic traditions of Asia, and to ensure a pleasant experience in calm and open spaces.

The ground floor galleries of the Guimet focus on India and South-east Asia, centred on stunning Hindu and Buddhist Khmer sculpture from Cambodia. Don’t miss the Giant’s Way, part of the entrance to a temple complex at Angkor Wat.

The Indian section also includes objects that highlight the relations between India and the Roman Empire during the 1st century CE; sculptures depicting the Buddha and episodes from Buddhist legend and effigies of various deities of the Brahmanic pantheon.

There are also outstanding Indian art and textiles from the Jean and Krishna Riboud collection along with one of the most beautiful sets of works of art and jewellery of India from the 17th to the 19th centuries that were donated in February 2000.

On the first floor, there’s Afghan glassware and Moghul jewellery, arts of Pakistan and the Himalayas. In the Peshawar region on the Indo-Afghan border, archaeologists found artefacts from the first empire of the steppes (1st-3rd century CE), providing evidence that the region was at the crossroads of three worlds: Greece, China and India.

There’s Greco-Roman glassware, lacquerware from the Han Chinese period and the oldest known ivories from India. The Himalayan objects include ancient Nepalese and Tibetan bronzes, 12th century painted book covers, metal sculptures whose dates range from the 11th-19th centuries as well as several wooden images from the 16th century.

The Chinese collections comprise more than 20,000 objects covering 7 millennia of art. Beginning with the Neolithic period that include mysterious jade discs and ceramics, bronzes from the Shang and Zhou dynasties, numismatics, a complete panorama of the history of Chinese ceramics, lacquered wood and rosewood furniture up to the 18th century.

Painting is represented by 1,000 works ranging from the Tang to the Qing dynasties. From its sheer quantity, it’s easy to understand why these treasures are spread over the two upper floors.

As well as Chinese objects, the second floor displays Korean and Japanese artefacts. There are approx. 1,000 works in the Japanese section, offering an extremely rich and diversified panorama of Japanese art since its origins during the 3rd-2nd millennia BCE, right up to the Meiji era (1868).

They illustrate in particular the phases of terracotta vases and figurines, the essential developments of Buddhist art in Japan, an important set of sculptures and delicate paintings on silk from the 8th-15th centuries.

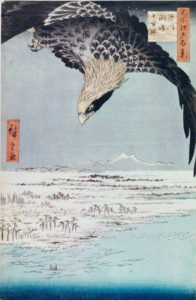

There are beautiful screens from the 16th-19th centuries, and fine examples illustrating the history of Japanese painting, in particular that of Ukiyo-e (the so-called “floating world”), notably works by Hokusai and Hiroshige.

There are nearly 3,000 prints that were collected at the beginning of this century, donated by major collectors. Finally, there are lacquers, ceramics, including Tea Ceremony stoneware and porcelain, ivories (netsuke) and sword hilts, evoking the diversity of Japanese applied arts.

The Korean collection started with the artefacts from a mission from Seoul to Pusan by Charles Varat in 1888, taken on behalf of the French Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts with the help the first French diplomatic representative at the court of Seoul, and that of the government of Choson Korea (1392-1910). The aim was to introduce to the French public the culture of a country that was very poorly known.

In 1893, a Korean gallery was opened in the museum that presented the arts of Korea in its most varied aspects. After 1945, there was a new interest in archaeology (particularly gold), alongside the fascination for Korean celadon—which are among our own personal favourite exhibits.

There are now over 1,000 items, among them bronzes from the Koryo period and paintings from the 17th-19th centuries. One of the most beautiful pieces is an eight panelled painted screen from the 18th century.

The library on the third floor has a fine collection of both European and Asian books and journals—in excess of 100,000 volumes and 1,500 periodicals. These cover European books form 17th-18th century, 700 titles from the Japanese Edo period, over 2,000 Tibetan works, as well as Chinese maps from the Qing dynasty, fragments of Uighur manuscripts, Urdu texts, and numerous orientalist academic papers.

Also on this floor is the History of Sound Archives, first started in 1933, that recorded ancient Asian musical traditions and are now considered very rare and fragile. There is also an exceptional photography collection dating back to the 19th century that documents aspects of all the Asian cultures that are represented in the museum.

Visitors can take a tour called ‘L’Asie Maintenant’ (Asia now), that encompasses the original collections and more than 150 recently purchased works. This practice is very much in keeping with Émile Guimet’s wishes, as he was a firm believer that museums should not be stuck in the past but had a policy of growing their collections with an eye to the future. In 1889 he said his mission was for “a museum that thinks, a museum that talks and a museum that lives.”

After immersing yourself in such visual wonders of cultures we still know relatively little about, it’s time to head to the delightful café on the lower ground floor. Named the “Salon des Porcelaines”, unsurprisingly the food has an Asian theme, and the space is decorated with some lovely porcelain pieces in glass cases to admire while you relax. We always head here for a spot of lunch after enjoying the visual riches of the exhibits.

Also on the ground floor is a particularly good boutique-bookshop. The merchandise and books are inspired by the masterpieces kept at the museum. I can personally recommend the jewellery, silk scarves and lovely tableware.

Among many “must-haves” there is a selection of beautiful Japanese prints by the most illustrious Japanese artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige, Tibetan Singing Bowls, reproductions of Buddha sculpture from Angkor Wat and stunning art books you’d be hard pressed to find elsewhere. The shop is to the left of the reception hall.

The Musée Guimet offers a totally different cultural experience to what visitors normally expect to find in Paris. Although its exterior has largely retained its original appearance, the building’s interior is very modern, light and spacious, which sets off the treasures on display perfectly. Despite the contrast, the result is a harmonious and very pleasant, relaxing experience. Keep an eye out for street posters advertising special exhibitions—these are always outstanding, and not to be missed if you’re in Paris at the time.

Another thing not to miss is the Japanese garden and tea pavilion, perfect for quiet relaxation, and where Japanese tea ceremonies are also performed. A stone’s throw from the museum, at a wing of the Musée Guimet, the Hôtel Heidelbach at 19, Ave. d’Iena, constructed in 1913 by the architect Rene Sergent for the wealthy banker, Alfred Heidelbach.

The building was purchased by the French Ministry of Education in 1955 and further renovated in 1991.

This is where the superb Galeries du Panthéon Bouddhique are presented. Unique in the Western world and even Asia, these collections reveal the scope of Buddhist piety, and are presented as they would appear in Buddhist temples within a hierarchy of saints, divinities, kings of science, bodhisattvas and buddhas.

Musée Guimet is open every day except Tuesday from 10.00am – 6.00pm.

It’s located at 6, Place d’Iéna, in the 16th arrondissement. The nearest metro is Iéna (Line 9), which is just across the street, and Boissière (Line 6). A 5 minute walk across the Pont d’Iéna will take you to the Eiffel Tower.

For lovers of haute couture, just a few minutes’ walk away is the beautiful Musée Yves St Laurent at 5, Ave. Marceau. For more details, see my blog from 2018: https://parisplusplus.com/paris/musee- yves-saint-laurent-paris

Another suggestion: for a special treat, take a 3 minute walk a little further down to no. 10 Ave. d’Iena and check out the gorgeous Hotel Shangri-La. It was built in 1896 for Prince Roland Bonaparte, grand-nephew of Napoleon, and the renovations beautifully restored this relatively small palace to its former grandeur. It’s the perfect venue for a relaxing glass of champagne!

Cheryl,

Thank you so much, this was fascinating, not only the museum but the extras to do nearby. A real must see in Paris.

Bonjour Marguerite,

Lovely to hear from you, and so glad you enjoyed the latest story. We’re actually here in Paris now (hence, the “bonjour”!). We arrived a week ago for 3 weeks before heading down to the Burgundy district, an old favourite. We love the Musee Guimet, and recommend it to anyone coming here as something utterly different to anything else in the city, but also just a great place to visit in a part of town that many visitors simply don’t know much about. We’re going to try and pop into the YSL museum nearby, if we can fit it in, but there’s so much in the city that’s new since we were last here (thanks to COVID), and although we’ve got a list of “must sees”, I have a feeling we won’t be able to get to all of them. Fortunately, now it’s pretty much back to normal regarding travel, and everything open again here, we can say “next time” with confidence!

Thanks again for your very kind comments.

Cheers for now,

Cheryl