MATISSE: A MAJOR RETROSPECTIVE IN PARIS

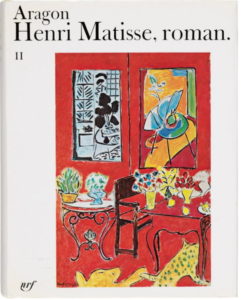

The Pompidou Centre is celebrating the 150th anniversary of the birth of Henri Matisse, one of the most important artists of the 20th century. This special exhibition uses a novel published in 1971 by Louis Aragon, Henri Matisse: Roman as a framework to display not only 230 works, but also over 70 documents, books and archives related to him.

“What I dream of is an art of balance, purity, and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter…a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.” – Henri Matisse.

This exceptional and highly original exhibition pays tribute to the modernist master, Henri Matisse, exploring a new side of the artist by focussing on the relationship between the painter and literature. The curator of the Musée National d’Art Moderne—the Pompidou Centre—brings together major classic works by Matisse in a way that gives the viewer an opportunity of rediscovering them by presenting them in a new light. There are many rarely seen works, and some that haven’t been on display to the public before.

Matisse exhibitions don’t happen very often, and this is the biggest retrospective devoted to the artist since the one held in 1970 at the Grand Palais in Paris. The works on show here come from the Pompidou Centre’s own collection, and supplemented by the collections of two museums devoted to Matisse, the Musée Matisse at Cateau-Cambrésis in the north of France, the Musée Matisse in Nice, as well as the Grenoble Museum and loans from private collections around the world.

Matisse was a late starter as an artist. He initially studied law in Paris and after graduation, worked as a court administrator in his home town of Le Cateau-Cambrésis. He first started to paint in 1889 after his mother bought art supplies for him during a period of convalescence, following an attack of appendicitis. He discovered “a kind of paradise” as he later described it, and decided to become an artist, much to the bitter disappointment of his wealthy grain-merchant father. He returned to Paris to study art, becoming proficient in painting traditional landscapes, still lifes and copying Old Masters in the Louvre.

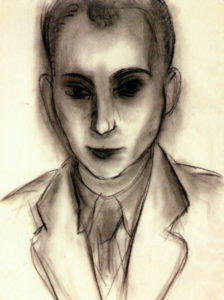

As a young man, Matisse studied with Gustave Moreau, who presciently told his late-blooming student: ‘You are going to simplify painting.” Louis Aragon, on the other hand, was convinced that Matisse would “make painting more complicated.” However, it seems that by the end of his long life, Matisse did simplify painting.

At the beginning of the show, we see him experimenting, perhaps even floundering, as most young artists do: painting in the classical style but at the same time, experimenting with Impressionism and Pointillism.

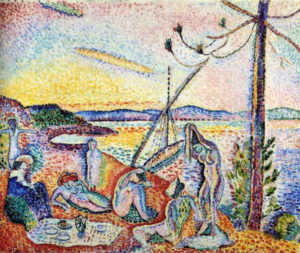

He didn’t come into his own until he associated with what were to become known as the Fauvist artists around 1905. Fauvism was the first of the avant-garde movements that flourished in France in the early years of the 20th century, and Matisse was naturally drawn to it. There is an example of his transition from Pointillism to Fauvism in this exhibition, with his ‘Luxe, Calme et Volupte’ painted in 1904, which he exhibited at the 1905 Salon des Independants–the painting was promptly bought by Paul Signac.

This is the period when his paintings exploded into loud, clashing colours, attracting the attention of the critics when some of his works were shown in a room at the Salon d’Automne. One shocked critic declared the room to be la cage aux fauves—the cage of wild beasts. However, he also attracted the attention of important collectors such as the Steins (Leo, Gertrude, Michael and Sarah), and the Cone sisters of Baltimore. ‘The Siesta’ painted in 1905 during a visit to Collioure during his Fauvist period, is in the exhibition.

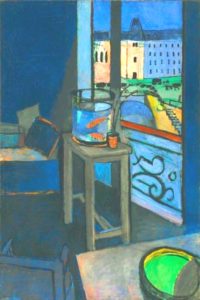

It wasn’t long though before Matisse moved on from his short Fauvist period, concentrating on more decorative works, often with numerous textile wallpaper patterns, and frequently seen through an open window, thereby connecting the indoors with the outdoors. One of his landmark paintings from this time, Interior with a Goldfish Bowl, depicts the bowl by the open window looking out on the Seine, with the red fish almost seeming to swim in the river.

The exhibition tells the story of Matisse’s life, presented like a novel in nine ‘chapters’, retracing the artist’s life and work, setting out his career in chronological order, from his artistic beginnings in the 1890s, to his close examination of the Old Masters, during which time he gradually developed his own artistic “language”, until the early 1950s. Each period of his life is interspersed in the exhibition with a literary interlude to remind us of the origin of some of his works and his relationship with major authors.

The writer Louis Aragon wrote five essays about Matisse, and these, together with unpublished letters and documents, enabled Aragon to construct his book, which is more akin to a biography than a novel. The exhibition shows the way in which literature acted as a creative source for the painter, and highlights how the painter’s pictorial language changed and developed. Each of the nine sections is enhanced by the viewpoint of an author who focused on Matisse’s work, not only Louis Aragon, but others such as Duthuit, Fourcade, Greenberg, Hind, Schneider, Clay, and finally with Matisse himself. But it also shows how Matisse incorporated literature into his own distinctive idiom, demonstrating how his art could also function as a form of literary criticism.

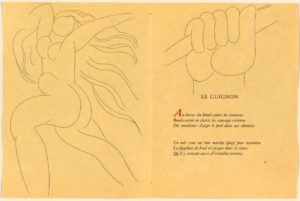

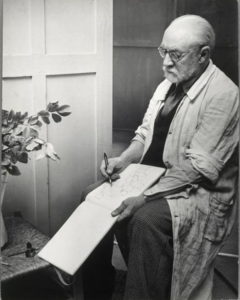

Matisse began exploring literature as a source of inspiration when, in 1932, he was engaged by the publisher Albert Skira to illustrate a deluxe edition of a selection of Stéphane Mallarmé’s poems with 29 full-page etchings.

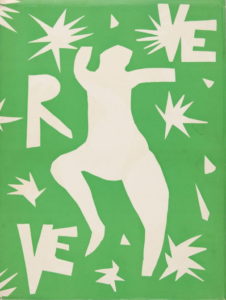

This was Matisse’s first venture into the art of the illustrated book, which continued on with illustrations for other volumes of poetry by Ronsard, Baudelaire and Charles d’Orleans, among others, as well as his many cover designs for the art magazine Verve. Describing his approach to illustrating books that he always strove for “rapport with the literary character of the work”, and “I do not distinguish between the construction of a book and that of a painting…”

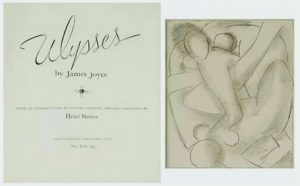

In 1935 he was commissioned to do a series of etchings for James Joyce’s Ulysses, and instead of illustrating the modern story, he returned to the ancient legend to find his subjects for the six plates.

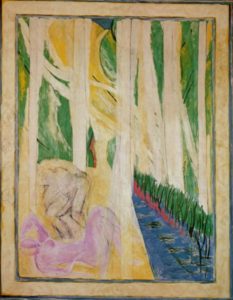

A number of his iconic paintings come from this period in the 1930s, such as La Verdure (also known as Nymph in the Forest), now in the Nice Museum. It’s thought that this painting was also probably intended to become a tapestry.

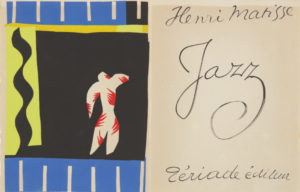

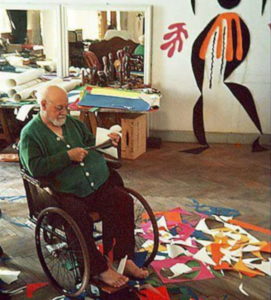

In 1947, Matisse produced one of his landmark works, Jazz, a book containing paper cut-out collages alongside his philosophical musings and calligraphic notes.

He resorted to this medium when ill health made it impossible for him to paint. At the end of his life, cut-outs became not just a stopgap but his primary medium.

Matisse’s genius for colour burst into full bloom with these wonderfully decorative pieces, which he used for designs for projects such as theatre sets.

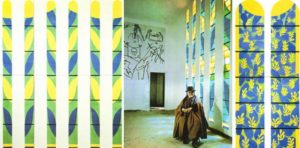

One of the most original uses of his cut-out technique was for the stained-glass windows and vestments for the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence on the French Riviera for a convent of the Dominican Order. Matisse himself regarded this project as his “masterpiece.”

Important as it was, it was not only literature that influenced Matisse. His travels were also a great source of creative stimulation, and his journey to Tahiti, made at the age of 60 in 1930 inspired a number of his cut-out works. In particular, Tahitian tapa—bark cloth decorated with geometric designs—and bedspreads known as tifaifai, fuelled this aspect of his art. “The light of the Pacific is a deep cup of gold into which we gave,” the artist said. “There is too much to see…sometimes I feel my stay in Tahiti has rekindled my imagination.” The myriad works included in the exhibition clearly show that the search for newness was essential for Matisse.

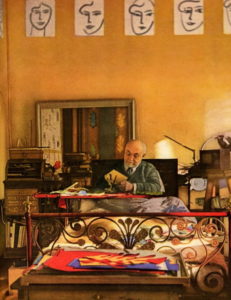

The poet Louis Aragon first met Matisse during World War II. A communist and an active member of the French Resistance, Aragon fled to Nice with his wife, the Russian author Elsa Triolet. Matisse lived nearby, so Aragon introduced himself and the two became friends.

He would hang out in the studio while Matisse worked, and socialise with him outside of work. Their conversations and letters reveal an intellectual, even spiritual, bond. Through his insightful writings, Aragon reveals that Matisse was not painting modernity, he was painting Matisse.

“Every canvas,” wrote Aragon, “every sheet of paper over which his charcoal, his pencil, or even his pen wandered, is Matisse’s utterance about himself.” Aragon was convinced that modernity was just an essential part of who and what Matisse was.

An overview of the works included in ‘Matisse: Comme un Roman’ (Like a Novel) clearly illustrates that the search for newness was essential for Matisse. He worked his way through numerous distinct stylistic changes throughout his career. One quote from 1942 hints that this was an intentional pursuit connected to what Matisse hoped would be his legacy: “The importance of an artist,” he wrote, “is measured by the quantity of new signs that he will have introduced into plastic language.”

For the first time, this important show displays works representative of all the techniques that Matisse tirelessly developed: drawing, painting, sculpting, engraving, paper cut-outs. An exceptional exhibition of Matisse’s body of work that has never been seen together before, it provides us with a unique glimpse into his approach to creativity, and how literature was one of the most consistent influences in this process.

If my story were ever to be written truthfully from start to finish, it would amaze everyone. Henri Matisse

NOTE: ‘The Sorrows of the King’ was Matisse’s final self portrait. This work refers to one of Rembrandt’s paintings, ‘David Playing the Harp before Saul’ in which the young hero plays to distract the king from his melancholy, but also refers to Rembrandt’s late self portraits. Here, Matisse depicts the themes of old age, of looking back towards earlier life. It also makes reference to the title of a poem by Baudelaire, ‘La Vie Antérieure’, that Matisse had illustrated.

Wonderful. ‘Interior with goldfish bowl’ is my favorite.

Love the fish too! One of our favourites is the view through the window, which was a favourite aspect of Bonnard, who admired Matisse. Glad you enjoyed the story–pity it’s as close as we can get to being at the exhibition!