LE CHÂTEAU DE VINCENNES – A MEDIEVAL FORTRESS IN PARIS

When you think of châteaux in the Paris area, Versailles is likely the first that would spring to mind. For its sheer beauty, opulence and size, not to mention the wonderful gardens and parklands surrounding it, it’s no wonder that Versailles is one of the most visited destinations in the entire country. However, for those who have “been there, done that” and would like to explore another former royal residence in Paris, the enormous Château de Vincennes offers a most interesting contrast.

It’s surprising how little-known the Château de Vincennes is to visitors, especially given its fascinating and turbulent history, not to mention how easy it to get there. Located on the eastern edge of the city in the 12th arr., it’s the terminus of Line 1, the busiest metro line in Paris. The Château is less than a 5 min. walk from the metro.

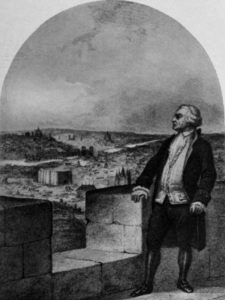

The Château de Vincennes is an imposing 14th century fortress which has stood at the heart of French history since its construction. Over the centuries, this Paris landmark has served as a prison, a fortress, and the site of numerous royal births, marriages and executions.

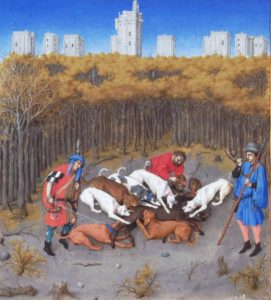

Like many other châteaux, Vincennes started out as a hunting lodge, constructed for Louis VII around 1150, allowing him access to the nearby forest of Vincennes. In the 13th century, Philip Augustus and Louis IX erected a more substantial manor house. The story goes that Louis IX departed from Vincennes on the 8th crusade to the Holy Land in 1270. However, Louis died shortly after arriving on the shores of Tunisia, and his disease-ridden army dispersed back to Europe shortly afterwards.

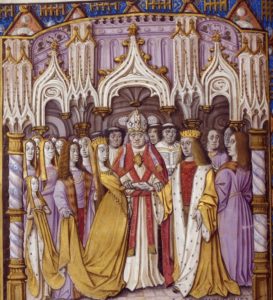

Vincennes was more than a formidable fortress. It was the location of royal events such as the second marriage of Philippe III in 1274, and Philippe IV was married there in 1284. Three 14th century kings died there: Louis X in 1316, Philippe V in 1322 and Charles IV in 1328.

Typical of other royal residences, Vincennes underwent numerous additions and alterations over the centuries. To strengthen the site, the Château was virtually rebuilt and enlarged in the 14th century to provide better security for the royal family in times of unrest.

Charles V’s original intention was to turn Vincennes into a second capital of the kingdom, alongside the Palais de la Cité in Paris, in an appropriate and grandiose setting that proclaimed the ideology of a triumphant monarchy through its size, quality and opulent décor. Unfortunately, this grand vision was never fully realised.

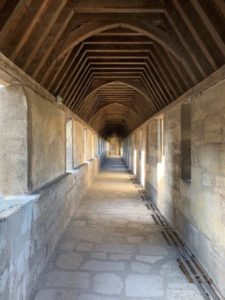

The Château is surrounded by a 1100m long fortified wall with nine towers, and is also protected by a moat 27m wide, with a drawbridge over it. A donjon, or Keep, 52m high, which is still the tallest medieval fortified structure in Europe, was constructed in 1365 by Charles V, and the royal family used it as a residence, since it was the safest location in the château. One of the Keep’s rooms was the king’s personal study and library, which held Charles’ considerable art collection, priceless manuscripts and, it was rumoured, sacks of gold and silver.

A Council Chamber was located on the first floor, while the King’s private apartments occupied the second floor. Access to the Keep is via a footbridge into the Tour de Village, which is a Châtelet/gatehouse that somewhat resembles a small château. The huge Keep is immediately visible on the right, while the chapel is opposite that.

At the southern end of the complex there are two large side wings facing each other, the Pavillon du Roi and the Pavillon de la Reine built by the architect Louis Le Vau for Louis XIV.

The bell tower, built in 1369, housed the very first public clock in France, and forms part of the gate to the donjon/Royal Keep. The clock was located above the King’s study and on the same level as his bedroom.

After his decisive victory over the French at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 during the Hundred Years’ War, Henry V of England (also known as Henry of Monmouth), in a political and diplomatic move designed to strengthen his claim to the French throne, married Catherine de Valois, daughter of the French King, on 02 June 1420 at Troyes Cathedral. It is thought that he had contracted dysentery during the siege of Meaux, and had to be carried on a litter to the Château de Vincennes, where he died in the donjon on 31 August 1422. His body was repatriated to England and buried in Westminster Abbey on 07 November 1422.

From the 15th century to the 1800s, the château’s Keep was used as a prison, a symbol of absolute State power, which saw the imprisonment of a number of famous figures during its history.

Henry IV was imprisoned at Vincennes in April 1574 during the Wars of Religion, and Charles IX died there the following month. Louis XIV’s Minister of Finances, Nicolas Fouquet (the unlucky builder of Vaux-le-Vicomte), was imprisoned at Vincennes during his trial for embezzlement of royal funds. In 1691 another unwilling lodger was John Vanbrugh, who went on to become a playwright and the architect of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard in the UK—it’s thought that he drew some of his Baroque “gothick” ideas from his experience of Vincennes. Working undercover, he had been arrested at Calais while in transit through France on a charge of espionage, carrying secret messages from William of Orange concerning the position of James II of England. He was released in November 1692 in an exchange of political prisoners.

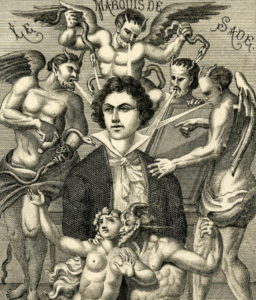

The infamous Marquis de Sade was incarcerated twice in Vincennes. The first time for violent behaviour in a brothel, the second imprisonment was for life for poisoning a prostitute. He spent 7 years in his cell at Vincennes before being transferred to the Bastille in 1784.

During his imprisonment, the Marquis de Sade met another famous prisoner, the Marquis de Mirabeau, who, like the Marquis de Sade, was notorious for writing erotic works, although it seems the two loathed each other. Mirabeau languished in Vincennes until his release in August 1782.

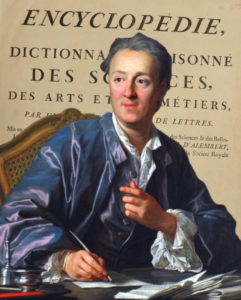

The French writer, art critic, scientist and philosopher, Denis Diderot, who became a prominent figure during the Age of Enlightenment, was imprisoned in Vincennes from July to November 1749 because of his controversial writings. These covered a range of topics including evolution, and a well-reasoned criticism of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle that had been signed by the two protagonists, Britain and France, as well as numerous inflammatory essays relating to religious tolerance and freedom of thought.

In more recent history, Dutch-born Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, better known by her stage name, Mata Hari, was shot at Vincennes after her conviction for being a spy for Germany during WW1. As a Dutch national, she had freedom of movement during the war, and travelled between France and the Netherlands via Spain and Britain and it’s generally agreed that she was in fact, a double agent for France while being in the employ of Germany. The archetype of the seductive female spy, she was a famous exotic dancer and courtesan, with a catalogue of lovers that included high-ranking military officers and politicians of various nationalities. She was arrested in her room at the Hotel Elysée Palace in Paris on 13 February 1917, put on trial, and executed by firing squad 8 months later on 15 October. Her body was not claimed by any family members and was accordingly used for medical study. Her head was embalmed and kept in the Museum of Anatomy in Paris. In 2000, archivists discovered that it had disappeared and its whereabouts are still unknown.

The beautiful Gothic chapel was constructed in 1379-80 within the fortifications of the Château during the reign of Charles V originally to house the relics of the Passion of Christ. The model for it was Ste Chapelle on the Ile de la Cité in Paris, and is just as high but not quite as long, and nor was there quite the same level of interior decoration. During the reign of Charles VI, the choir, the two oratories, the sacristy and the treasury were all completed.

The Hundred Years’ War and resulting financial problems delayed the completion of the Château’s chapel, it wasn’t completed until the middle of the 1500s during the reign of François I. You can see his emblem of a salamander on the pinnacle in front of the altar, along with the monograms of Catherine de Medici, and Charles IX. The chapel housed the Crown of Thorns and the other holy relics in the treasury while the Paris Ste Chapelle was being readied to receive them. A fragment that remained behind was kept in the chapel at Vincennes.

The interior decoration of the chapel was only finished under Henry II, who in 1551 moved the seat of the Order of St Michael to the Château de Vincennes from Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy. The following year Henry inaugurated the chapel.

In 1793 during the Revolution, the interior decoration was destroyed, much of the stained glass windows were smashed, and the Baptistère de Saint Louis, which had been used as the baptismal font for children of the royal family, was moved to the Musée du Louvre. As a result, the chapel is no longer used as a church and is rather bare inside. However, there are beautiful stained glass windows, some of which were damaged during the Revolution, and later in WW2. These have been restored to their former 16th century glory.

The chapel houses the tombs of Bernardin Gigault, Marquis de Bellefonds, who was appointed Marshal of France in 1668 under Louis XIV, and Louis Antoine, Duc d’Enghien the last descendant of the House of Condé. At the age of 31 he was executed in 1804 in the moat of the Château on charges of aiding Britain and plotting against Napoléon. He was originally buried in a nearby grave, but when Louis XVIII returned to the French throne he had the Duc’s remains exhumed and removed to the chapel in 1816. In 1825 a funeral monument to the Duc was commemorated, but this was moved from the nave in 1852 as part of the restoration of the keep and chapel by Viollet-le-Duc on the orders of Napoléon III.

No longer used as a royal residence when Louis XIV moved to Versailles, the Château de Vincennes was all but abandoned by the 18th century. It played almost no part during the Revolution other than serving as an arsenal and military garrison.

The disused Château had become the site of a porcelain factory in 1740, known as the Manufacture de Vincennes, until this was transferred to Sèvres in 1756, renamed, and where it remains today. The Château then became a state prison.

After its restoration by Viollet-le-Duc, Napoleon III gave the Château to the city of Paris in 1860 along with the Bois de Vincennes, recreated in the English landscape style, as a public park.

Vincennes served as the military headquarters of the Chief of General Staff, General Maurice Gamelin, during the unsuccessful defence of France again the invading German army in 1940. On 20 August 1944, during the battle for the Liberation of Paris, 26 policemen and members of the Resistance, arrested by the Waffen-SS, were executed in the moat of the fortress, and their bodies thrown into a common grave.

In 1949, the Château became a repository for army archives as well as a library with 140km of shelves, and is now the main base of France’s Service Historique de la Défense (Defence Historical Service). There’s a superb Louis XIV reading room decorated with paintings from the same period. The Service also maintains a most interesting museum for the three French armed forces in the donjon.

Interestingly, there is a (not so) secret Plan Escale in place, which is an evacuation plan of the Elysée Palace—the official residence of the President—to the Château de Vincennes in event of floods. The Elysée Palace, in the 8th arr. of Paris, is in a flood zone, and it’s thought that Vincenne’s 52m high Keep would provide a most effective refuge for the President in the event of a major flood of the Seine. To date, this plan has never been triggered, but the Chateau de Vincennes is ready if necessary!

Heading through the Château gate nearest the chapel, you will see the Bois de Vincennes to your left.

There are many beautiful walking paths in the bois, and at its heart is the Parc Floral de Paris, which is the Botanical Garden of Paris.

During June and July, the Paris Jazz Festival features a large number of concerts over the 8 weekends of the festival.

Well – the poor old Marquis de Sade was a slow learner and

Marta Hari faced the firing squad and misplaced her

head oh dear!

Hi Nadine. The Chateau is a fascinating place. There may not be lavishly furnished rooms etc., but its history more than compensates for that, when you think who some of the “reluctant guests” were over the centuries. I think the Marquis rather brought his problems on himself. His writings, even by today’s standards, are “extraordinary”! He could combine sado-masochism with extreme erotic fantasy, good old fashioned pornography and poetry. Needless to say, people read it in order to be shocked etc. Regarding Mata Hari, it has been thought that she was a scapegoat to draw attention away from the incompetence of so-called military “intelligence”. Perhaps she was just a naughty girl with a wide circle of friends in high places who had been indiscreet too many times! Cheers, Cheryl