LA SAMARITAINE, AN ICONIC PARISIAN DEPARTMENT STORE REBORN

La Samaritaine has finally re-emerged, like the phoenix rising, if not from the ashes, from a long hibernation of neglect and deterioration that left a gap on the city skyline between the river Seine and the busy rue de Rivoli. Its recent re-opening was a much anticipated event. After 16 long years of closure, renovations, and some controversy, this historic icon is the ultimate grand magasin. Definitely a must-see on your next visit to Paris!

La Samaritaine on the rue de Rivoli takes up most of the block before the Louvre, and lies directly in front of the quai du Louvre and rue de la Monnaie. The store occupies 4 buildings, 2 of which are connected by a bridge over rue Baillet at the rear. The most conspicuous of them is the newly constructed building along the rue de Rivoli. With its rippling, glass façade, it was a highly controversial design. It was refused development approval by the City of Paris authorities, and ultimately ended up in a long Court battle, where the City eventually lost the case, and the development was allowed to proceed.

The new building certainly makes no attempt to fit in with the adjacent original stores—or anywhere else on the street—and having once been inside and wandered around, we don’t feel we ever need to go back!

The restored original buildings however are a different story entirely. They are utterly gorgeous! For many years, we’d walk past them and could only wonder what they must’ve been like in their heyday. The golden mosaics and cast-ironwork decorating the façades were filthy from decades of dirt and neglect, and the entire complex was a truly sad sight to behold, and impossible to ignore, given their size and in such a prominent location.

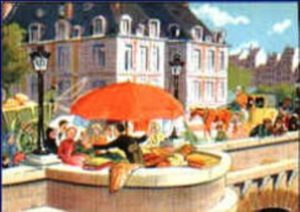

In 1603, King Henri IV commissioned an engineer to construct a pump house at the second arch of the Pont Neuf bridge. This was completed in 1607, and the structure was decorated with a statue of “La Samaritaine”, the woman at Jacob’s Well in the New Testament Gospel of St John. The pump house and its statue were dismantled in 1813 and replaced by a floating public swimming pool complex.

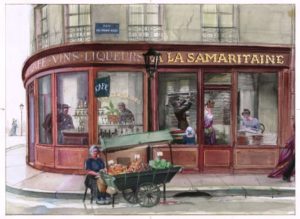

The origin of La Samaritaine dates back to 1869. It started out as a small shop selling novelties owned by Ernest Cognacq. The shop was no more than a room adjoining a café. After some trial and error, it became a raging success, and in 1872, Ernest married Marie-Louise Jaÿ, at that time the leading female sales assistant in the dressmaking section of Le Bon Marché dept. store.

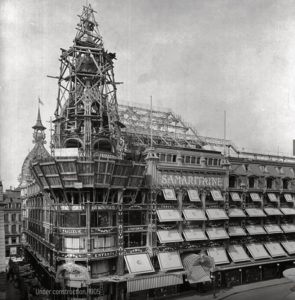

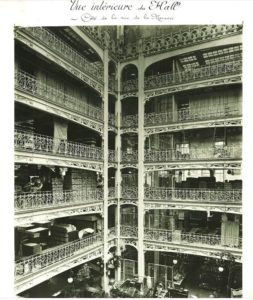

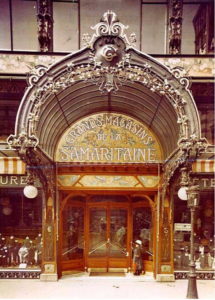

From 1890 to 1910, Ernest gradually acquired property bordered on the north side by rues de la Monnaie, Baillet, de l’Arbre-Sec and des Prêtres-Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois and converted the existing buildings into retail space. On the southern side he commissioned architect Frantz Jourdain to design and construct a building with a riveted steel frame supporting a huge glass roof, decorated in the newly fashionable Art Nouveau style. The northern and southern sections were unified by steel and glass façades adorned with glazed lava stone panels. Les Grands Magasins de la Samaritaine were born.

Ernest Cognacq was born in Saint-Martin de Ré on the Ile de Ré off the coast of La Rochelle, the son of a ruined maritime broker. He was orphaned at the age of 12 and had to give up any idea of academic studies, and although he had dreamed of becoming a sailor, instead, he went to work as a draper’s assistant in a fancy goods store in La Rochelle. He then worked as a clerk in Rochefort and Bordeaux before going on to hawk wares in Lyon, Avignon and Marseille before landing in Paris in 1854. He was laid off work at the brand-new Magasins du Louvre and faced poverty. He walked home to La Rochelle but was back in Paris in 1856 and fell in love with a young salesgirl, Marie-Louise Jay when they were both working at La Nouvelle Heloise. In 1867, he had finally saved up the sum of 5,000 francs and opened his own shop. This was a failure, and once again, Ernest had to go back to the life of an itinerant vendor.

He eventually set up in one of the corbeilles (‘baskets’) on the Pont Neuf, sheltering under a big, red umbrella, close to the Samaritaine pump house. Finally, he had a success, opened a little shop next to the café, and was able to marry Marie-Louise. They were a formidable retail duo, worked extremely hard, spent very little on themselves, and poured every profit back into their burgeoning business and expanding it with large new stores.

Following the great success of the stores designed by Jourdain between 1905 – 1910, in the 1920s Cognacq commissioned him to expand the store with a large, new addition. Aware that architectural fashion had changed, and Art Nouveau was now regarded as rather old-fashioned, the new building was built in the innovative Art Deco style. This was designed by Jourdain’s partner, Henri Sauvage, as Jourdain’s name was too closely associated with a style from the past. When the new building was completed in 1928, it still featured the cream coloured Parisian stone and also made use of exposed steel, however, it’s much more geometry-based. At the end of construction, La Samaritaine consisted of four separate stores.

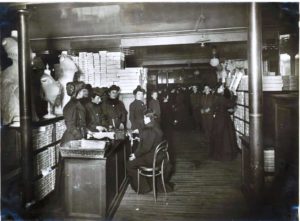

Due to the store’s large turnover, Cognacq was able to buy in bulk at the lowest possible price, and overheads were kept down. Aiming as it did to a broad public, “La Samar”, as it was affectionately referred to, did not flaunt a luxurious atmosphere, or palace-like decor. Unlike the very up-market Le Bon Marché, it did not have an elegant tearoom or reading room, or sell exotic imported goods such as Oriental rugs, timber decorative objects from Lebanon or fine porcelain from China.

However, the store was known for its excellent customer service as well as being a generous and considerate employer with a well-developed social conscience. Employees enjoyed family allowances as well as sick pay, a nursery, gym, a theatre and opera society, sanitorium, retirement and convalescent homes as well as an orphanage, holiday camps and affordable housing.

The architectural design of La Samaritaine was largely inspired by the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle. Although other department stores had already used metal frameworks, these tended to be covered over, at La Samaritaine the structure was itself visible on the façade. This gesture followed the example of the American architect Louis Sullivan with his Schlesinger & Mayer building in Chicago. Metal architecture was efficient to install, and also created space and improved brightness, increasing the useable area by doing away with stone outer walls and proving perfect natural lighting through panels of the glass roof. The recent renovation has preserved the original façade and restored the glass roof to its original state.

Jourdain said that the aim of the decorative façades of the buildings was to create “art on the streets”. Thanks to its colours and ornamentation, the buildings contributed to an urban aesthetic that was free for all to enjoy. Its creation was a collective effort by draughtsmen, painters, decorators and sculptors, under the direction of the architect. The result was an exuberant decoration of enamelled ceramic panels in shades of yellow, blue, green and gold cladding the pillars and beams of the metal structure. At street level, hammered copper plaques and panels of carved wood surrounded windows and doors. During the restoration, the Centre for Research and Restoration at Musées de France were able to reproduce all the colours, so what we see today is very close to the originals.

By the 1970s, La Samaritaine’s glory days were well and truly behind it, sales were in terminal decline and the store finally closed in 2005, ostensibly due to major building safety concerns. By this time, the store had been taken over by the Renant family after WW2. Ernest Cognacq-Jay had died in 1928 and his nephew took over, but he lacked the flair for retail of his uncle, the “great selling machine”.

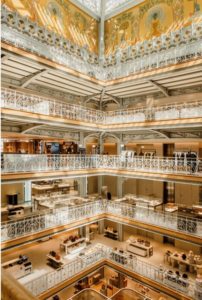

Luxury goods behemoth LVMH acquired the whole site in 2010 and the lengthy restoration program commenced, involving the restoration of two atriums, and the creation of grilles, portals, balconies, railings, ramps, and other examples of fine metal work, particularly on the monumental staircase.

The Toronto/New York firm, Yabu Pushelberg, redesigned the art nouveau interior, now known as the ‘Pont Neuf’ side. As the designers recall, the original brief was aimed at foreign tourists, but they were determined that the store maintain a Parisian flavour. ‘La Samaritaine had been a big, giant, glorious general store for the people of Paris,’ says George Yabu. ‘So we thought, why don’t we make it resonate with the locals as well?’

The company set out to find a balance between history and modernity. Taking the ornamental art nouveau context as a challenge, such as the original bright egg yolk yellow, they managed to soften the shade. The store’s colours are now an eye-pleasing mix of golden tones, such as bronze metals and blonde woods, and the ironwork’s original grey-blue. Rather than interior walls, the designers divided the spaces with custom-made rugs and furniture in simple shapes and classic materials.

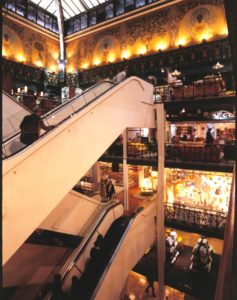

Another major measure was to remove the 1960s era escalators and reinstate new ones in a more sensitive manner. The retail portion of the buildings is around 1,860 sq.m. offering more than 600 different brands—many of which are owned by LVMH—a spa and beauty salon, numerous bars and restaurants, plus around 1,400 sq.m. of office space, plus a hotel. LVMH’s owner, Bernard Arnault, is said to have spent more than €750 million on the refurbishment and renovation program, and now the whole complex is managed by by the DFS Group, of which LVMH is the majority shareholder.

Unlike the original La Samaritaine, the new incarnation, which opened in June 2021, has been re-born as an ultra-luxury hub, with a dizzying selection of top end designer labels, both French and international fashion as well as shoes and accessories. The basement level is now home to the biggest beauty department in Europe, covering the entire 3,400 sq.m. footprint of the store.

Have a browse through the Boutique de Loulou, the ultimate classy souvenir shop for all things French, such as embroidered brooches from Macon et Lesquoy, and wax fabric “Amour” pillows from CSAO, limited edition Plakat home décor posters and vintage catalogues, pretty Parisian-themed stationery, notebooks and mugs, and even bikes to cycle your way along the banks of the Seine.

The re-opening also saw the inauguration of a new palace hotel from the 5 star Cheval Blanc group, occupying the iconic Art Deco building facing the Seine on Quai du Louvre. Although the historic building has retained a sense of its Art Deco heritage, it is distinctly contemporary in spirit—a plush, elegant cocoon in tones of beige and white with flashes of gold. No sooner had the hotel opened than its restaurant, ‘Plenitude’, on the hotel’s first floor, was awarded 3 Michelin stars for its chef, Arnaud Donckele. The hotel also boasts a panoramic terrace with views from the Eiffel Tower to Montmartre, and from Notre Dame to Centre Georges Pompidou, as well as a luxurious Dior Spa, the perfect place to be pampered far from the madding crowd.

La Samaritaine is an absolute must-see on your growing list of exciting new projects to explore on your next visit to Paris. As well as admiring the beauty of this enormous Art Nouveau restoration project, there are many things to discover, aside from luxury designer names, a beauty studio and spa, wines and spirits.

As you’d expect, there is a fine dining restaurant ‘Voyage’ offering three separate eating areas, a ‘Krug’ Studio on the top floor, as well as a choice of numerous other dining options, including a fresh juice and salad bar as well as patisseries such as a branch of Parisian favourite, Eric Kayser.

The motto of the original La Samaritaine was “On trouve tout à la Samaritaine” (“One can find everything in La Samaritaine”). Although it must be said that this temple of luxury makes no attempt to cover the variety and breadth of say, Galeries Lafayette or Au Printemps, or even the deluxe Au Bon Marché, it’s wonderful to see this grande dame restored to its former glory.

Wow – I could definitely spend a few hours here

and give the plastic card a good workout.

Hi Nadine,

Yes, this is dangerous territory for the plastic, although I must say, the real attraction for me is just seeing these beautiful buildings restored to their former glory. A pleasure indeed to visit.

Cheers, Cheryl

This will be of particular interest to my French friend, Alexandrine , who used to live on Ile de Re.

Hi Lois,

Your friend may very well be familiar with Ernest Cognacq from her years on Ile de Re. He’s likely known as a “local boy made good”, and with good reason, when you consider his background. A remarkable success story indeed, but also due to his extremely progressive social programs that he instituted for his staff–well ahead of his time. He would have been a most interesting person to have known I’d imagine.

Best regards, Cheryl