ART NOUVEAU TREASURES OF THE PARISIAN BELLE ÉPOQUE

The Belle Époque lasted from the 1870s to the beginning of World War One, and was at its height in Paris during the 1890s and 1900s. It was a period of great optimism and cultural innovation. It was an exciting time for art and theatre, as well as a new architectural movement generally referred to as Art Nouveau, which swept across Europe. It was an era of confidence, prosperity and certainty, and Parisians in particular were hungry for more glamour, more beautification, and elegance.

Following the long siege of Paris, the French suffered the humiliation of German occupation following their defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, and consequently, the collapse of Napoleon III’s Second Empire. A radical, revolutionary government, known as the Paris Commune, emerged for a few short months in 1871. During violent confrontations across the city, the Hotel de Ville, many Haussmann style buildings, including a number of buildings along the bustling rue de Rivoli, and symbolically, the Palais des Tuileries, were destroyed by fire. On 28 May, the city was reclaimed by the French Army.

Some buildings were able to be restored, but most required a total rebuild. These projects ushered in a new period of architecture, creating some of the most spectacular monuments in Paris, as was the case throughout Europe. However, Art Nouveau was not just an architectural movement, but rather, a complete style that included art, furnishings and interiors, fashion and jewellery. It was a mixture of baroque, oriental and classical elements, in parts strongly influenced by Japanese art—a complete break from traditional forms. It was a time before the First World War when mass manufacturing got its start and the absinthe was flowing.

For the exponents of this new style, beauty meant proportion and decorative detail. From silverware, wallpaper, lighting and textiles, artists were dedicated to creating a complete, immersive experience. Floral motifs were a characteristic, as was an absence of straight lines or right angles. It was a complete contrast to the heavy, somewhat ponderous, style of the preceding era. The basic elements of Art Nouveau are the colours, glass, light, and honey-coloured wood for interior decoration, and the use of cast iron in architecture.

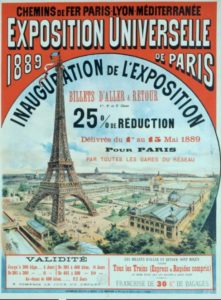

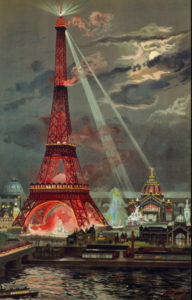

The most spectacular example of the use of cast iron in Paris at this time was the Eiffel Tower, constructed as the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair. It was very controversial at the time, with numerous people pushing for its demolition after the Fair, on the grounds of its size (324m) and in their view, its intrusiveness in the cityscape, but also because of its design and material, which they detested. For many others though, the Eiffel Tower was a symbol of French engineering pride and innovation. It was a time when arts and crafts, cafes, restaurants and various forms of theatre became increasingly available to a rapidly growing middle class with time and money on its hands. For them, this new style represented a changing world in which they could participate rather than merely as onlookers or attendants to the aristocrats of the past.

Art Nouveau had first appeared in Brussels, in houses completed in 1893 by Victor Horta and others, and across Europe from Budapest, Prague, Riga and as far away as St Petersburg. An outstanding exponent of this new style of architecture was Antoni Gaudi, whose many extraordinary buildings in Barcelona demonstrate the influence on him of the Moorish history of Spain.

Gaudi’s buildings are often covered in dazzling, colourful mosaics—many made of natural stones, with few even surfaces, creating forms that are full of fantasy, and pushing the boundaries of the style. Even the gigantic (and still yet to be completed) Sagrada Familia church complies on the whole with these attributes.

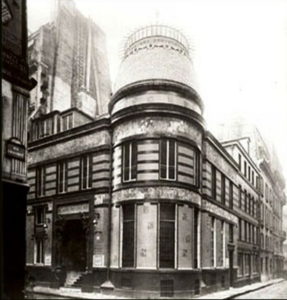

The Art Nouveau style quickly appeared in numerous forms in Paris. It was introduced by the Franco-German art dealer and publisher, Siegfried Bing, who wished to break down the barriers between traditional museum art and decorative art. In 1895 he opened a new gallery, the ‘Maison de l’Art Nouveau’, at 22 rue de Provence in Paris, devoted to works in both the fine and decorative arts that featured the new style. He also set up a pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 under the same business name.

An interesting piece of history from that exhibition that you can see today is the ceramic portico of the Manufacture de Sevres pavilion, which can now be seen in the Square Félix-Desruelles, next to the Église de Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

Another of the great Parisian monuments to the Belle Epoque that’s such a pleasure to walk across and enjoy is the Pont Alexandre III, connecting the Right Bank at the bottom of the Champs Elysees across the river to the Invalides and Eiffel Tower. Constructed in 1900 in time for the Exposition Universelle as a diplomatic gesture to the Russian Tsar with whom the French had signed an alliance a few years before. It’s built in the Beaux Arts style and richly decorated with Art Nouveau lamps, cherubs, nymphs and winged horses at either end and has four gilt-bronze statues of Fames (Science, Arts, Commerce and Industry) restraining Pegasus the mythical winged horse, supported on 17m high plinths.

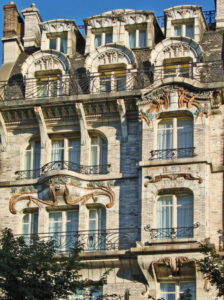

Although the Art Nouveau movement was short-lived, it changed the face of Paris forever. It enlivened the severity and regularity of Haussmann’s Second Empire style, with colour and movement. The development of new building materials and the relaxation of building codes allowed a new wave of architects to create buildings that were revolutionary both in form and in ornamentation. Façades became undulating, balconies were stepped or staggered, and everything was decorated with naturalist motifs such as flowers, trailing vines, animals and the female form. Structural materials were now used as décor, and new colours enlivened the façades by the use of ceramics, tiles, sculptured stone, stained glass and of course, wrought iron.

The uncontested leading light of the movement in Paris was Hector Guimard, who designed such gems as the incredible Castel Beranger at no. 14 and the Hotel Mezzara at no. 60 rue Jean de la Fontaine in the 16th arr., and his own house at no. 122, avenue Mozart, also in the 16th.

But of course his most conspicuous legacy was the Métro station entrances he designed dotted across the city—there are 86 remaining from the original 141.

More than 400 Art Nouveau buildings were erected in Auteuil and Passy in the 16th arr. However, it was in the somewhat staid 7th arr. that two of the most extravagant examples of Art Nouveau are to be found. The hôtel particulier (large private townhouse) at 29, ave. Rapp, is considered the masterpiece of Jules Lavirotte, a fervent practitioner of sexual symbolism in architecture. Salvador Dali once remarked that it was the most overtly erotic building in Paris.

While other architects were sculpting flowers, fantastic creatures or idolising the female form, Lavirotte was pushing the boundaries on the ave. Rapp building. Its façade is tiled, decorated with allegorical figures, the balconies are in sinuous wrought iron, but it’s the entrance that will stop the viewer in their tracks. Crowned with the head of a woman (possibly Madame Lavirotte), framed by stylised foliage and figures depicting the disgraced Adam and Eve, the central door is shaped to resemble an inverted phallus sculpted in timber and leadlight glass. Sexual symbolism is repeated on the balconies of the ground floor windows.

Although his designs provoked considerable controversy, nevertheless Lavirotte won the coveted Concours des façades organised by the city of Paris, no less than three times—the first in 1901 for 29, ave. Rapp. His Hôtel Céramic (also a winner) in the 8th arr. is a pared-down Art Nouveau building, announcing his more refined, less flamboyant style to follow. He abandoned Art Nouveau in 1902, as he felt the need to move on due to the number of imitators who, in his view, had betrayed the spirit of the movement’s ideals. There are 9 of his Art Nouveau buildings still standing in the 7th arr.

One of the city’s prettiest Art Nouveau buildings is a short walk away from 29 ave. Rapp. The ‘Maison des Arums’ at 33, rue du Champ de Mars, designed by the architect Octave Raquin. It has a sculpted stone façade of arum (or calla) lilies, around the bow windows and supporting the balconies, and the lily motif is repeated in the wrought iron grilles and balconies, while flowers and leaves are depicted on the windows and transoms. The lily has traditionally represented the female anatomy, but the building was not a “house of ill-repute” as the use of this motif might’ve suggested, but rather, a highly respectable private school for young ladies of the bourgeoisie, run by two sisters, the Misses Longuet. It was later occupied by another school, and today it’s a cosmetic surgery clinic.

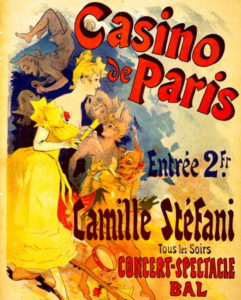

The Art Nouveau movement was not restricted to architecture. The painters Gustave Klimt, Alfonse Mucha and master lithographer Jules Chéret were very prominent during this time, producing not only paintings, but menus and posters for the theatre.

Czech-born Mucha moved to Paris in 1887 and found success designing posters for products such as champagne, chocolate, cigars and much more.

However, it was the poster he created for the Theatre de la Renaissance in 1894 for the darling of French theatre, Sarah Bernhardt that gave Mucha his big break. Promoting the theatre’s production of ‘Gismonda’, the poster was almost 2m high and went up all over Paris. Bernhardt was thrilled with the result and signed a contract with Mucha that lead to the creation of seven posters for her over a period of five years, including ‘La Dame Aux Camélias’, which became one of Mucha’s most iconic works.

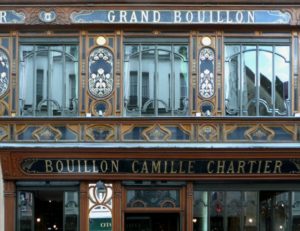

As Paris is a city that values beauty more than most others, it wasn’t long before even humble cafés felt they could profit from having a makeover in the new style that was fast becoming all the rage with the increasingly prosperous bourgeoisie. A number of these casual establishments, known as bouillons (originally serving bouillon broth and other simple meals) were transformed into grand dining rooms, more appealing to this fashionable new age.

One of the most famous of these is Chartier, at no. 7, rue du Faubourg Montmartre in the 9th arr. Founded in 1896 and classified as a monument historique since 1989, it still serves down to earth, comfort food at very moderate price–there’s also a branch in Montparnasse.

Another beautiful Art Nouveau restaurant to track down, established in 1906 by the Chartier brothers, is Le Bouillon Racine, at 3, rue Racine in the 6th arr., near Odeon.

There are so many other Art Nouveau restaurants and cafes in Paris, and one of the most beautiful is to be found unexpectedly at a railway station. I’m referring of course to the spectacular ‘Le Train Bleu’ at Gare de Lyon. Created for the Exposition Universelle of 1900, its interior is dazzling. Each section of the restaurant is themed to represent cities and regions of France, and decorated with 41 paintings by some of the most popular artists of the day. If you’ve never seen it, put it on your “must see” list.

One of the most famous restaurants in the world must surely be Maxim’s, at 3, rue Royale in the 8th arr. Founded as a bistro by Maxime Gaillard in 1893, it has had a series of owners who have all respected and cared for the wonderful Art Nouveau interior. It was so famous that the 3rd act of Franz Lehar’s 1905 operetta ‘The Merry Widow’ was set there. The current owner, fashion designer Pierre Cardin, has created an Art Nouveau museum on the upper floors full of furniture and objects collected by him.

The restaurant has featured in many films over the years, including ‘La Grande Illusion’ by Jean Renoir in 1937, the musical ‘Gigi’ in 1958 and Woody Allen’s 2011 film ‘Midnight in Paris’ the 2011, just to mention a few.

The Art Nouveau style was adopted for many purposes and buildings for numerous uses. If you’re in the neighbourhood, check out the former grocery store of Felix Potin, at 140, rue de Rennes in the 6th arr. Built in the Art Nouveau style 1904, the building had fallen into disrepair after the Felix Potin business closed, but has recently been renovated and its Art Nouveau exterior restored.

Next time you’re in Galeries Lafayette, just spend a few minutes from the shopping experience to look up at that fabulous glass cupola and the balconies on each floor! Inaugurated in October 1912, it reaches a height of 43 m. from the ground floor. It’s as spectacular today as it was when the store first opened.

If you’re a collector of objects d’art, Paris is the ideal place to acquire a stunning piece by René Lalique. Sarah Bernhardt was a great fan, and by wearing many of his pieces, helped him become famous.

Not only renowned for his lighting, but for so many other exquisite pieces such as his beautiful perfume bottles, vases and jewellery in the Art Nouveau style. If your budget doesn’t run to a purchase, head to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, next to the Louvre in the rue de Rivoli, to see a fine collection of Lalique jewellery as well as fashion of the period by Paul Poiret.

The Art Nouveau movement couldn’t survive the catastrophic disruption of WWI, but luckily for us, there’s so much of the Art Nouveau still to see in Paris. These examples here should be just enough to tempt you to discover some of them.

To see one perfect example that represents the cross-over from Art Nouveau to the new, emerging Art Deco style, head to the stunning Hôtel Lutetia, at 45, Bvd. Raspail, for a delicious afternoon tea.

Founded by the owners of the nearby Bon Marché department store, the Lutetia is the only luxury Palace hotel on the Left Bank. This architectural gem, dating from 1910, has recently re-opened after an extensive renovation that has seen it restored to its former glory. What better way could there be to end a day exploring the riches of the Art Nouveau of Paris?

As always, a fascinating read. Thank you.

Hi Nadine,

There’s some incredibly beautiful Art Nouveau things to look at in Paris, and I particularly love the jewellery and fashions that are on display in the Musee des Arts Decoratif, especially the Lalique pieces. It was certainly a “gilded era”!