A DRAMATIC TRANSFORMATION OF A LONDON ICON

Since it was decommissioned in 1983, the Battersea Power Station had stood derelict on the south bank of the River Thames. Renowned for its four chimneys and Art Deco design, after decades of decay, the iconic Grade ll* heritage listed building has undergone a massive transformation, opening in late 2022. This complex project has opened the building and riverside to the public for the first time, retaining the power station’s unique historical features, but giving it a new 21st century purpose.

Many people who have never been to London are nevertheless familiar with the Battersea Power Station. Immortalised on screen in such films as Hitchcock’s 1936 film ‘Sabotage’ (before the B Station was built), ‘The King’s Speech’, Ian McKellen’s ‘Richard lll’, and the 2008 Batman film ‘The Dark Knight’, the building is an enduring feature of the Thames skyline. The power station gained notoriety from exposure on Pink Floyd’s 1977 album cover that featured flying pigs, which shows an inflatable pink pig floating above it. It was tethered to one of the southern chimneys, but broke loose from its moorings and drifted into the flight path of Heathrow Airport. The album itself was officially launched at an event at the power station.

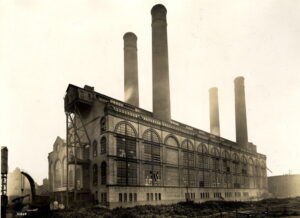

Located close to the edge of the River Thames in Nine Elms, Battersea, an inner-city district of South West London, the Battersea Power Station was built by the London Power Company to the design of two architects, J. Theo Halliday, responsible for the majestic Art Deco interior, and the renowned Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who designed the jazz-age exterior. It is one of the world’s largest brick buildings. The building actually comprises two power stations, built in two stages, but within a single building. Battersea A Power Station was built between 1929 and 1935 and Battersea B Power Station, to its east, between 1937 and 1941, when construction was paused owing to the worsening effects of WW2. This building was finally completed in 1955, and built to a design nearly identical to that of Battersea A, creating the iconic four-chimney structure we see today.

Until the late 1930s, electricity was supplied via local municipal councils. There were small power companies that built power stations dedicated to a single industry or group of factories, and sold any excess electricity to the public. These companies used widely differing standards of voltage and frequency, which often created disruptions, if not havoc, throughout the country, particularly for heavily industrialised cities. In 1925, the British Parliament decided that the power grid should be a single system with uniform standards and importantly, under public ownership. The London Power Company proceeded to build a small number of very large stations. The first of these was planned for the Battersea area on the south bank of the River Thames, which would be used for cooling water and coal delivery. Plans were submitted and the proposal sparked protests from many people who felt that the building would be too large and would be an eyesore, as well as concerns about pollution damaging local buildings, parks and even paintings in the nearby Tate Gallery!

The distinguished architect and industrial designer, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott—famous for his designs for the red telephone box and Liverpool Anglican Cathedral—managed to assuage such concerns. He subsequently designed another London power station, Bankside, which now houses the Tate Modern Art Gallery. The pollution issue was resolved by the incorporation of a method of treating emissions to ensure they were “clean and smokeless”.

The A Station first generated electricity in 1933, although it was not completed until 1935. The total cost of its construction was 2,141,550 GBP—a staggering sum of money for those times. There were six fatal and 201 non-fatal accidents on the site during construction. The construction of the B Station in the post-war years of the 1950s, provided a fifth of London’s electricity needs and was the most thermally efficient power station in the world when it opened. Battersea kept the lights on in the Houses of Parliament and Buckingham Palace (codenamed Carnaby Street 2 in the power station’s control room) before puffing its last plumes of smoke in 1983. At its peak, Battersea was burning 10,000 tonnes of coal a week to produce 509MW of electricity, about 20% of London’s needs, which was delivered by a huge railway network.

The Battersea Power Station was decommissioned between 1975 and 1983 and remained empty until 2014. It was designated as a Grade ll listed building in 1980, and in 2007 its listed status was upgraded to the higher status of Grade ll*. In 2008 its condition was described as “very bad” by English Heritage, and it was included on its Heritage at Risk Register. The site was also listed on the 2004 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund.

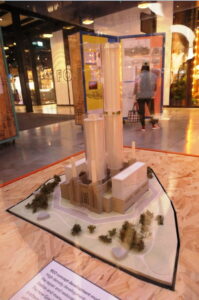

Since its closure, numerous redevelopment plans had been drawn up by successive site owners, but none was successful. One of the numerous doomed ideas, back in the 1980s, was to turn it into a theme park, while another scheme planned to gut the complex and erect massively tall, glass residential towers within the space. Then, in the 2000s, there was a plan to build a 300m-high “eco chimney” next to it, a proposal which was described by then-London mayor Boris Johnson, as looking like an inverted toilet roll holder.

The biggest redevelopment problem had been the sheer scale of the structure, combined with its very poor condition. It was seemingly too damaged, too expensive, and perhaps too big to rescue. Constructed from six million bricks, the power station covers more than 2 hectares. St Paul’s Cathedral could have fitted into the main boiler house alone. The roof was removed in the late 1980s as part of the crazy theme park proposal, exposing the building’s steel frame to the elements. The chimneys were breaking up because they were badly cracked, exposing the steel reinforcement to the elements, further exacerbating corrosion and decay.

Given its sad state of decay, many said the sensible thing was to demolish the power station after it closed, but this option was ruled out because of the upgrade to a higher level Grade ll* listed status in 2007. This meant anyone taking on the building had to restore it, and the cost of doing so overwhelmed many prospective developers. It was not until wealthy Malaysian investors, first in 2012 and another Malaysian consortium in 2018, took on the project at a cost of 1.6bn GBP. The cost of restoration and refurbishing eventually spiralled from 750m GBP to over 1.15bn GBP. The job has been described as “the Everest of real estate” and “the toughest project in the world”. Fortunately, the end result has generally been regarded as a triumph.

While the 4 chimneys had to be replaced with reinforced concrete replicas, many of the original features of the power station were retained, including the two control rooms, one with Art Deco flourishes and herringbone parquet floor, the other in more brutalist, 1950s style, as well as ceramic wall tiles, exposed steel beams, remnants of staircases and the former directors’ entrance. Overhead travelling cranes have been retained and incorporated into the design, with one holding a footbridge spanning Turbine Hall A.

Throughout the restoration process as much of the existing fabric as possible was retained and conserved. The power station’s distinctive brickwork has, where necessary, been meticulously recreated by two firms that made the bricks for the original buildings, supplying 1.75 million matching replacements.

Its layer-cake arrangement, with some connection between the disparate parts, is bold and clever. Six floors of workspace take up the top half of the boiler house, while at the bottom, more than 100 shops and restaurants arranged around the former turbine halls occupy three floors.

The Turbine Halls on either side of the central boiler house are the main retail spaces and are quite different in character, reflecting the fact that the building was completed in two halves, A & B, 15 years apart.

Within Turbine Hall A, three tiers of shops surround a central atrium that is topped with a glass and steel skylight. The space’s original columns were restored, with dark-coloured steel frames placed between each one to give the shop façades a unified appearance.

The later 1950s Turbine Hall B has a slightly different and more industrial aesthetic in keeping with its later construction. In its roof, all of the circular extraction fans have been replaced with light tunnels to allow natural light to enter the space, while a gantry crane supports a dramatic-looking fully-glazed box for use as an event space.

A bar has been created in the 1950s control room.

A food hall connects the two main Halls. There is also a gym, a cinema, contemporary art galleries, and exhibition spaces in the complex.

Alongside each of the turbine halls, the original control rooms have been refurbished. The jewel in the crown of the building, the control room of Turbine Hall A, has been beautifully restored with parquet flooring, Art Deco roof lanterns, Italian marble panelled walls and a glorious cornucopia of dials, switches, knobs and mahogany control desks. The 1930s control room has been turned into an events space that is regularly open to the public. This is the hall to go for premium fashion labels, whereas Turbine Hall B has more of an eclectic mix of contemporary brands.

The switch houses at the eastern and western extremities of the building have been converted into apartments and are fairly modest in scale. These retain the same black-painted riveted steel and exposed brick quality of the rest of the building. The two-storey glazed extensions over the switch houses offer residents access to secluded rooftop gardens from where they have views of the neighbouring boiler house wall and the four iconic chimneys that tower over the whole complex.

The upper levels of the Boiler House have become Apple’s new London headquarters, now the workplace for more than 1,500 staff, across six floors. Cantilevered above the Boiler House are 18 “Sky Villas”—luxury apartments nestled among roof terraces and gardens. These are among 254 apartments making up the residential component of the complex. Also located within Battersea Roof Gardens is London’s first, so-called “art’otel”, with 164 rooms.

Built very close—some would say too close—to the power station are apartment blocks designed by the US architect Frank Gehry in his distinctive style with fragmented forms, and one large, curved structure, the Battersea Roof Gardens, designed by Foster + Partners. However, it’s acknowledged that this was a necessary compromise in order to make the project economically viable.

A grand pedestrian “high street”, Electric Boulevard, runs from the south of the power station between Gehry’s Prospect Place and Foster’s Battersea Roof Gardens, and further along to the new Battersea Power Station Underground Station. It brings together a varied and interesting mix of high-end fashion, bars, restaurants, leisure and entertainment venues. There are also wine bars, breweries and sunset cocktails along the riverfront.

As an additional attraction, on the reconstructed north-west chimney, a glass elevator, called Lift 109, has been installed that whisks passengers up 109 metres to an eyrie on top, affording a 360 degree view over London’s skyline. Tickets for this must be purchased in advance, and it doesn’t come cheap at 15.90 GBP per adult. Pre-booking is strongly recommended, due to its popularity.

Not unsurprisingly, the whole project has not met with universal approval. Critics point out that here is little affordable housing, and none inside the power station. There are about 386 affordable homes, some distance from the power station on the other side of the main road that make up less than a tenth of the total for the site. Wandsworth Council, the local administration, boycotted the opening ceremony in protest at the development’s low level of affordable housing. Another critic sniffed that “it took 40 years just to create a shopping mall!”

However, despite these very valid criticisms, it is an extraordinary achievement to bring this legendary London landmark back to life, and has been the impetus to a much-needed rejuvenation of the entire neighbourhood. It’s now very easy to get to, either on the extension to the Northern Line to the new Battersea Power Station underground station, by numerous buses, or by walking across the Chelsea Bridge and strolling along the Riverside Walk. Don’t miss this exciting addition to the many attractions to enjoy on your next visit to London.

My, what a resurrection! bet it looks magnificent in the flesh.

it is great to see the site being reused/recycled after so many years.

Hi Tony and Annette,

Yes, you’re absolutely right: it looks absolutely terrific! We’d become so used to seeing it sad and neglected for decades, and had given up hope of ever seeing anything positive happening to it. It’s got a lovely, buzzy vibe as you walk around and through it, and people are really using every bit of the complex, whether its cafes, bars, the cinema, the variety of shops etc., and attracts every age group, not just for hip young things, which is a great outcom.e That area of London, in the past never exactly a desirable or remotely interesting, neighbourhood to go to, even when the power station was fully functional–is suddenly hot property! We’d certainly re-visit it on a future trip to London.

Great to hear from you! We must have a lunch together soon, at our “usual”.

Cheryl (& Graham)