TWO ART DECO WONDERS IN LILLE, NORTHERN FRANCE

The City of Lille in the north of France is one of the loveliest in the country. Although largely unknown outside France, Lille has so much to captivate the visitor. From a beautiful historic quarter, much of which is pedestrianised, to great food, excellent shopping possibilities, and an enormous number of cultural attractions. Two of these are Art Deco gems, located outside the city in the suburbs of Roubaix and Croix, just a quick metro or tram ride from the city centre.

Roubaix was once famous for its textile production, an industry which had flourished there since the 14th century. In the 19th century, the city was known as the “French Manchester”, one of the world capitals of textiles. It was also called the “city of a thousand chimneys”, and its factories thrived well into the 20th century. It’s from those times that La Piscine Museum and the Villa Cavrois come.

The origin of La Piscine—the museum of art and industry—dates back to 1836, the date of the creation of the Roubaix industrial museum, in order to showcase the city’s contemporary textile production. In 1861, the museum widened its scope to the Fine Arts, which added to the rich textile collection. From 1902, the then director worked to break down the boundary between the Fine Arts and the decorative arts, and instigated purchases of modern art and Sevres ceramics from the Universal Exhibitions.

Around the same time, a local textile merchant bequeathed his artworks, which represents an important part of the museum’s current collections. The gift comprised paintings, drawings, sculptures and art objects, along with important works by Ingres, Fantin-Latour, Lépine and Gérôme, among others. In 1924, a local Roubaix painter, Jean-Joseph Weerts, known for his social portraits and public paintings, donated his studio’s collection to Roubaix, his birthplace. All the collections were housed at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts et Industries Textiles falling under State control, and renamed the Roubaix National Museum. However, as with all the other national museums, the Roubaix museum closed during WW2 and it never re-opened after the Liberation. Instead, the mixed collections were housed in the local Hotel de Ville.

In 1980, the new curator of the museum, Didier Schulmann, was keen to establish a new museum to house the Roubaix collection, as its home in the Hotel de Ville was no longer suitable, with severe space limitations. The presentation of a work acquired by the Louvre brought home the necessity of a dedicated space for Roubaix’s art works. Finally, in 1990, the municipal council approved the idea of transforming a former swimming pool into a museum.

The municipal swimming pool built in 1932, was commissioned by the Mayor and designed by architect Albert Baert. In its day, it was cutting edge design: a stunning Art Deco monument. It offered not just a swimming pool, but it also had bathrooms and change rooms for men and women. At a time when most poor people didn’t have access to such things, this was an innovation at the forefront of design for those times. It was much loved and very well used by the local people, and stayed operational until 1985, when its deteriorating condition necessitated complete renovation after chlorine in the water caused damage to the structure, especially the roof.

By then the textile industry had also declined and Roubaix found itself undergoing a dramatic change. The city councillors decided to ensure that the heritage of Roubaix was preserved and was awarded the title of “City of Art and History.” They needed somewhere to house their expanding art collection, and Bruno Gaudichon, who became the director of La Piscine, admits that choosing the former swimming pool as the location for a new gallery was “a gamble, as by now, Roubaix had a lot of empty industrial buildings.”

The municipal swimming pool had been left neglected for several years, and a public competition was held for architects to come up with a design for the building. In 1994 the winner was chosen—Jean-Paul Philippon, a French heritage architect who already had achieved a reputation for his contribution in converting the former Gare d’Orsay in Paris into the stunning Musée d’Orsay in 1979, and the Musée des Beaux Arts in Quimper, Brittany in 1993.

His plans for La Piscine centred around keeping the integrity and authenticity of the much-loved swimming pool. “I wanted to keep the basin of water” he said, and it is now the heart of the museum. “But I narrowed it to make room for the artworks. I created pontoons alongside, with ceramic lining created from the original elaborate mosaics. Thousands and thousands of tiny pieces were all carefully preserved. A number of the original changing rooms were kept, others were dismantled. It was like a giant Lego game putting all the pieces together and reconstructing it.”

In 2001, the municipal council allocated an adjacent former textile factory building to be part of the museum. One of the original walls still stands as a memorial to the old building after a section of it was demolished to let light in. It is, said Philippon, one of his favourite aspects. “In my design, I wanted people to be able to circulate easily. To see the collection as it should be seen, it was an important aspect of the museum.”

The museum’s collection include works by Rodin, Picasso, Pompon, Dufy, Busy and Eames. There are paintings, sculpture, textiles, furnishings ceramics and drawings. The 19th and 20th century collections are world famous and amongst the best in the world. Given that La Piscine is a beautiful example of Art Deco architecture, it’s a suitable home for so many objects and art works from that period.

La Piscine was an immediate, enormous success with an astounding 200,000 visitors in its first year. The Art Deco beauty of the museum proved the perfect backdrop for the growing collection of paintings, sculptures and textiles. The museum has won accolades, being voted the best museum outside of Paris, thus attracting even more visitors each year. In fact, it was so successful, that another competition had to be held to create an extension.

In 2011 Jean-Paul Philippon was again the winner, and the new extension of more than 2,000 sq.m. opened in October 2018. The new space is light and airy, there are rooms dedicated to temporary exhibitions, permanent exhibitions and special plinths to display specific pieces.

After viewing this wonderful museum’s collections, head to the in-house café when you’re in need of a little sustenance. Also, don’t forget to explore the excellent bookstore-gift shop before you leave, housed in the former pool’s filter room.

Barely 20 mins. from the centre of Lille, and approx. 3kms from La Piscine in the suburb of Croix is the Villa Cavrois. A jewel of modernist architecture, it was designed by one of the pioneers of the modernist movement, architect Robert Mallet-Stevens, a friend of Le Corbusier.

He designed the Villa as a “true modern chateau” to be the family home of wealthy textile industrialist Paul Cavrois, who had inherited his wealth from the family firm which had developed spinning and weaving mills for cotton and wool in Roubaix, where he had more than 5 companies and nearly 700 employees. He commissioned Mallet-Stevens to design a home to accommodate his family of 7 children, but above all, he wanted a healthy living environment for his family, out of the industrial inferno that was Roubaix. The site he chose was over 3 hectares in Croix, between Lille and Roubaix.

Cavrois had seen the work of Mallet-Stevens in Paris at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts, where it was seen as a great success “by many who cared for something more modern than the luxurious traditionalism of French Art Deco”. Two years later, Mallet-Stevens had completed the development of a street he had designed in Paris—now rue Mallet-Stevens in the 16th arr.—comprising six luxurious villas in a dramatically avant-garde, modernist style that confirmed his reputation.

On presenting his scheme to Cavrois, Mallet-Stevens said that in his view, “real luxury is to live in a bright, cheerful, airy, well heated setting, with as little as possible of unnecessary gestures and a minimum of servants.” Cavrois gave Mallet-Stevens free reign on the project, including design of the garden and a 27m long swimming pool. The 72m long pond in the park acts like a mirror, reflecting the house in its still water.

Built between 1929 and 1932, the Villa Cavrois was one of Mallet-Stevens’ finest achievements. He believed in a multidisciplinary approach and the collaboration of the arts, refused the use of ornaments and the non-essential—he even designed all the furniture. One of his governing principles was that “a home décor and living environment must reflect the psychology of those who inhabit it.”

Mallet-Stevens was known for his work designing film sets, and the lighting effects throughout the house in particular reflects his expertise in creating the Hollywood glamour of the 1930s. The Villa was astonishing for its bravery and modernity, and its design was totally different from that of other neighbouring houses, even those of the same era.

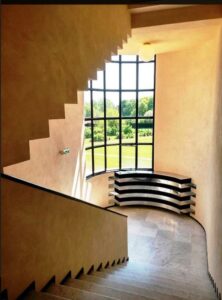

Even today, the clarity of design and the use of space is very impressive. The rooms are deceptively simple, with the lines, proportions and colours subtly perfect. The overall design of the house evokes the silhouette of an ocean liner, and its modernity further expressed by the strong vertical and horizontal planes, the fine metal frames of the openings, the presence of corner windows, the staggered terraces and the saffron yellow of the brick cladding.

Mallet-Stevens used thin, elongated bricks, accentuating the horizonal lines of the building by painting the bevelled, horizontal joints black, whilst the vertical joints are flush, with painted yellow mortar. Twenty six individual moulds were used to adapt the bricks to all situations, resulting in a flawlessly uniform, almost machined, yellow “skin”.

The floor plan of the villa was designed to reflect Paul Cavois’ views of how family life would be organised, how it might reflect the people who lived in it, how they would move around the building, and how that might be reflected in “décor for their daily life.” He wanted clear distinctions between the separate areas of the house, notably between parents’ and children’s quarters.

The house is organised around a large entry hall which welcomes visitors. The east wing is the domain of the parents, while the west wing is the domain of the children and staff.

The entry hall also gives access to the main rooms where the family gathered: the living room (salon) the dining room and a smaller dining room for the children, linked to the garden by an external staircase. Simplicity and functionality prevailed in the furniture throughout the house, with luxury expressed only in the richness of the materials used, such as marble, metal and timber.

The Villa embraced the latest modern technology of the day in all its rooms and spaces, using electricity for a sophisticated approach to lighting, the installation of radio loudspeakers, electric clocks and telephones with intercom. The house also had an elevator, air-conditioning, electric vacuum cleaning and towel heaters installed.

In 1939, with the impending advance of the German army, the Cavrois family abandoned the villa and moved to their manor in Normandy. The villa was occupied by German troops who turned it into a barracks for 200 soldiers. It was left in an appalling state when they were forced to retreat. The Cavois family returned in 1947, and the architect Pierre Barbe made various changes in order to house the families of Paul Cavrois’ two sons. Paul Cavrois died in 1965 and his wife in 1985. The furniture was quickly sold off and the villa purchased by a real estate company who planned to demolish it, subdivide the large garden, and sell off the lots for housing.

Although it was not listed as an historic monument until 1990, measures were put in place to prevent the demolition of the house, and an Association de Sauvegarde de la Villa Cavrois, with support from world renowned architects. In the face of such vehement opposition to their plans, the developers abandoned the house. It was quickly looted, ransacked and occupied by squatters, and ultimately abandoned. The Villa Cavrois had become a heritage and conservation scandal, and the desperate semi-ruinous state of the building, with the interior virtually a shell, made it hard to see how Mallet-Stevens’ villa could be repaired.

In 2001, the French Ministry of Culture bought the house, and determined to restore it. In 2004 restoration work commenced on the exterior and the reinstatement of the internal features. The restoration project cost 23 million Euros, and the result has seen the Villa magnificently restored to an extraordinarily high standard. One room on the upper floor has been intentionally left untouched to show the extent of the damage that was done in the decades before.

The gardens have also been restored, with replanting of trees, restoration of the water features and the original alleys, the illumination of the gardens and the villa itself. It also seems extraordinary that a surprising amount of the original furniture was located and purchased, to be reinstated into the Villa. Items that were unable to be traced were reproduced from documentary evidence, including Mallet-Stevens’ specifications, as well as photographs taken during the years of the Cavrois family’s occupation.

Getting to La Piscine: It takes around 30 mins. by metro from Lille station, taking line 2 to Gare Jean Lebas. The museum is 500m away. Alternatively, take bus line 32 or Z6 to stop ‘Jean Lebas’. La Piscine’s address is 23 rue de l’Espérance, Roubaix. The museum is closed on Mondays.

To get to Villa Cavrois, take the tramway to Roubaix and alight at ‘Villa Cavrois’, then it’s a 10 min. walk to the Villa. The address is 60, Ave. du Président Kennedy, Croix. Note that, like La Piscine, the Villa is closed on Mondays.

How wonderful these two unusual places have been resurrected to such fabulous condition and use.

Thank you for showing them to us, love your research.

Diane

Hi Diane,

Glad you enjoyed reading about these 2 gems. They’re both very interesting to see how difficult buildings–the very idea of re-using a swimming pool is fascinating, rather than taking the easy way out of demolishing and starting from scratch–and the Villa Cavrois was such a joy to see. When we saw the photos of what an appalling state it was in, we had such admiration for not only the quality of the restoration, but the sheer courage in tackling it. Nice to see what determination, as well as consumate skill, can achieve!

Cheers,

Cheryl