MONT SAINT-MICHEL, NORMANDY’S JEWEL IN THE CROWN

It is surely one of the most stunningly beautiful sights in Europe, and in its setting in a bay shared by Normandy and Brittany, Le Mont Saint-Michel draws the eye from a great distance. It has been a great Christian pilgrimage site from the early 8th century when a local bishop claimed that the Archangel Michael himself came to him in a vision and pressured him into constructing a church atop the island just off the coast. It’s safe to say there’s nowhere in the world quite like this magical island, topped by its Gothic-style Benedictine abbey that arises out of the bay like a heavenly apparition.

In prehistoric times, this rocky, tidal island was still part of the mainland. As sea levels rose, erosion reshaped the coastal landscape, and eventually several resilient granite outcrops emerged in the bay. Over the centuries, the connection between the island the mainland also changed. At one stage they were connected by a tidal causeway uncovered only at low tide, and this was converted into a raised causeway in 1879, preventing the tide from totally removing the silt that built up round the island.

The island we know as Mont Saint-Michel was used in the 6th and 7th centuries as a stronghold of Gallo-Roman culture and power until it was sacked by the Franks, thus ending the trans-channel culture that had stood since the departure of the Romans in 460. By the 9th century it was an important border for the western part of the Kingdom of the Franks. Before the construction of its first monastery in the 8th century, the island was called Mont Tombe.

The destiny of the island changed forever when in 708 Aubert, Bishop of the nearby town of Avranches, had a vision wherein the Archangel Michael appeared to him and instructed him to build a church on this rocky islet. Henceforth, the island was to be known as Mont Saint-Michel. Construction of the Abbey was itself something of a miracle. Boats transported granite from quarries in Chausey—a group of small islands off the Normandy coast—which was then cut into blocks and hauled to the top of the Mount.

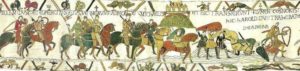

Its political fortunes also changed numerous times. Unable to defend his kingdom against the constant assaults by raiding Vikings, the king of the Franks agreed to hand over Mont Saint-Michel to the Bretons in 867. Although it was nominally a Breton possession, the island was never really included in the duchy of Brittany and remained an independent Bishopric until it became a dependence of the Rouen archbishopric. The Mount gained strategic importance again in 933 when it was annexed by William Longsword, the second ruler of Normandy, making it definitively part of Normandy, as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, where Norman knights are shown being rescued from the quicksand of the tidal flats during a battle with the forces of the Duke of Brittany.

Norman ducal patronage financed the spectacular Norman architecture of the Abbey in subsequent centuries—needless to say, the monastery of Mont Saint-Michel supported William the Conqueror in his claim to the throne of England. As a reward for this support, the monastery was given ownership of a priory on a small island on the south western coast of Cornwall, and renamed it St Michael’s Mount of Penzance.

During the Hundred Years’ War, the Kingdom of England made repeated assaults on Mont Saint-Michel without success, due to the abbey’s much improved fortifications. As an impregnable stronghold during these turbulent years, Mont Saint-Michel is an excellent example of military architecture.

Two cast-iron cannons, known as “les Michelettes”, abandoned by English forces from the siege of 1433-34 remain on the site as a reminder of the impenetrability of the fortress. A young girl from Orléans, whom we know today as Joan of Arc, was so inspired by the story of resistance at Mont Saint-Michel, she determined to help recapture France from the English.

In 966, Benedictine monks settled on Mont Saint-Michel at the request of Richard 1, Duke of Normandy. Under the authority of the Abbot, these monks were responsible for the growth of the new monastery. The Abbey very quickly became a major pilgrimage site and also one of the centres of medieval culture and learning, where a large number of manuscripts were produced and stored. The island was given the nickname “City of the Books”.

As an important political and intellectual centre, and despite endless cross-Channel conflict, over the centuries the Abbey was visited by a large number of pilgrims including several Kings of France and England, becoming second only to Santiago de Compostela in Spain in importance. Such was the difficulty of the journey, that it became a gesture of penitence, sacrifice and commitment to God to reach the Abbey.

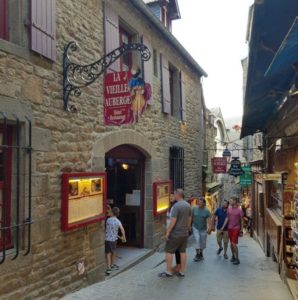

Mont Saint-Michel is a visible hierarchy of feudal society. On top there is God, then the Abbey and monastery; below this, the great halls, then stores and housing, and at the bottom, outside the walls, housing of the local fishermen and farmers. From the time that the Benedictines had established themselves in the Abbey, a village grew up below its walls. By the 14th century, the village had extended up as far as the foot of the rock.

Architecturally, the Abbey complex we see today is just the last of a long history of building works. Over the centuries and following fires, collapses, reconstructions, changes in use or restorations, the buildings occupying the site have been transformed. The first was a pre-Romanesque church, then in the 11th century a Romanesque abbey, and finally, in the 13th century, a sublime Gothic edifice, that became known as the “Merveille” (the Wonder). The Abbey, built on the summit of the Mount at 80m in altitude, sits on an 80m long platform, consisting of four crypts built into the spur of the rock.

This masterpiece of Norman Gothic art on such an inhospitable site bears witness to the architectural and engineering expertise of the 13th century builders. Comprising two buildings of three floors, it seems nothing short of a miracle that it perches on the perilous slope of the rock. It’s crowned by a large refectory and separate cloister, with an atmosphere conducive to meditation with the fragrance of herbs, flowers and the sea filling the air. Lastly, measuring 3.50m high, the slayer of the dragon of the Apocalypse, St. Michael, perches on the very tip of the Abbey’s spire, 156m above sea level.

Early in the 17th century, the Mount was deserted by its administrator abbots, and lost its importance in both military and religious terms. Fortunately, reforms within the Church lead to the Congregation of Saint-Maur establishing a new religious order at the Abbey. They redeveloped the site and attempted to revive the monastic life and encourage pilgrims to return. These monks also had to cope with the arrival of prisoners sentenced to imprisonment without trial, and the Abbey became a kind of “Bastille on the sea.”

Following the Revolution, the property of the Church was declared national property, the monks of Mont Saint-Michel were driven away, and the Mount became a prison for recalcitrant priests in 1793. In 1811, an Imperial decree transformed the Abbey into a reformatory, mainly for common law prisoners as well as political prisoners. Closed in 1863, the prison at least had been the saviour of the Abbey from destruction, but the monument was left in a terrible state of dilapidation.

In World War ll Mont Saint Michel was captured by the German Army on 18 June 1940 and used as an observation post. Wehrmacht soldiers held military manoeuvres in the shadow of the Mount as they prepared for Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of Great Britain. It was liberated on 01 August 1944 by the American 4th Armored Division.

The Abbey was classified as a historic monument in 1874, and the long, painstaking process of restoration began, and a causeway constructed in 1878 made access to the Mount easier. In 1969 a small community of Benedictine monks was established at the Abbey, who were replaced in 2001 by the Monastic Fraternities of Jerusalem. The Mount was listed as a World Heritage Site in 1979, making it one of the first French properties to be listed.

Thirteen centuries of history and its island location means that conservation and restoration are a constant challenge, along with the pressures brought by thousands of visitors and being so exposed to the elements.

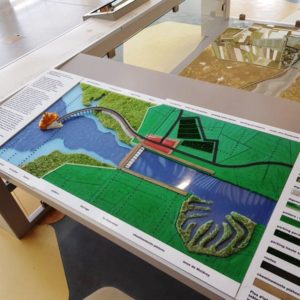

Surrounded by vast sandbanks and exposed to powerful tides, the bay of Mont Saint-Michel has been prone to silting up over the last couple of centuries. Activities such as farming and the construction of a tidal causeway that only uncovered at low tide, had added to the problem. A major conservation project started in 2015 has helped restore its island status to the Mount.

The main river into the bay, the Couesnon, has now been left to flow more freely so that sediments are washed out to sea, and a bridge has replaced the former causeway, enabling the sea once more to flow freely and fully surround the Mount at high tides. On rare occasions an extremely high “super tide” occurs—experts estimate once every 20 years. The last time this happened was on 21 March 2015, when the new bridge was completely submerged, and thousands of onlookers gathered to snap photos of the phenomenon.

The visitor car parks have been moved further inland to preserve the Mount’s exceptional setting and landscape. Visitors now head to the Place des Navettes outside the tourist information centre, where special, free shuttle buses, called passeurs, take you across to the Mount. The passeurs stop 450m away from the Mount itself.

Alternatively, you can book a special horse-drawn carriage (un maringote) or walk all the way from the car parks across to the Mount, which is the ideal way to take in the magnificence of the site as you approach.

I highly recommend spending some time in the new Visitors’ Centre, not far from the car park. It has great displays and information about the restoration project of the Mount, the landscape and ecosystem of the bay, including the construction of a dam over the river Couesnon upstream which increases the river’s hydraulic capacity and regulates its power to flush the channel and move sediment from the Mount.

Mont Saint-Michel is one of the country’s most popular sights, with around 2.50 million visitors every year. On the whole, it’s best to avoid school holidays and weekends if possible. While it’s possible to make a day trip from Paris, it’s a long and tiring journey.

Instead, plan to spend at least one night in the area, or even on the Mount itself, where there are a couple of small hotels, which should come as no surprise, given that the island’s village is pretty much given over to tourism, as is very clear from most of the island’s shops being devoted to tourist merchandise—some very good, some you can certainly live without!

Walking around the island on the mudflats is very popular, and if you fancy the idea, it’s best done with a guide who knows the timetable of the fast and very dangerous tides of the bay that reach up to 15m—the highest springtide in Europe. Enquire at the tourist office—the price for a guide is very low, something like €5. You can also buy your ticket for the Abbey at the tourist office—an adult ticket is around €11—which is a better bet than joining the long queue up at the Abbey.

Be prepared for lots of steep, cobblestoned pathways that lead to the top of the Mount, as well as a goodly number of stairs you need to climb, so be sure to wear comfortable walking shoes.

You also won’t want to miss the walkways on the ramparts that offer magnificent views over the bay.

One advantage of staying on the island for the night, if you’re planning a summer visit, is that there is a Son et Lumiere show in the Abbey grounds from about 7.00pm to 10.30m.

The first time we visited the Mount many years ago, we stayed on the island in a little hotel. However, the last time we visited Mont Saint-Michel we stayed in the beautiful town of Rennes, the capital of Brittany, and a medieval treasure. If this suggestion appeals, you can read more about Rennes in my Blog of 02 August 2018: https://parisplusplus.com/beyond-paris/rennes-brittanys-medieval-treasure

Rennes is about a 1.5 hr. train ride direct from Paris Gare Montparnasse, and it’s an ideal town from which to rent a car to explore the region. If you don’t wish to rent a car, there are buses from Rennes to Mont Saint-Michel that take about an hour, and drop you at the tourist office near the carpark. Another option is to stay at Saint-Malo (also possible by train from Paris Gare Montparnasse, but requires a change at Rennes), from where you can take a combo of train then bus to Mont Saint-Michel, and is a fabulous destination in its own right—see my Blog of 03 Sept. 2018 to learn more: https://parisplusplus.com/beyond-paris/st-malo-gateway-to-brittany

Thank you Cheryl. Brings back wonderful memories of visiting it, in August 2019. But I reckon that the Bishop who had the vision was probably on magic mushrooms !?

Hi Lois,

You could have something there! Those dark, cavernous spaces under the Abbey would’ve been the perfect spot for cultivating some very special crops–no-one would’ve known! Yes, it’s a magic place, isn’t it? The last time we went was the first visit we’d made since all the changes to the car park, the construction of the really excellent Visitors’ Centre and the new bridge/causeway etc. had been done. I’ve promised myself that next time, I’ll take a horse-drawn carriage ride across, as it was so popular with long waiting queues, we didn’t stand a chance that time.

I have to agree, it certainly does bring back wonderful

memories of an amazing place. I have a souvenir biscuit

tin which I probably bought at one of the tacky souvenir

shops – but I don’t care, I still like it.

Hi Nadine,

Yes, it’s certainly a stunning location, and the view from the top is unforgettable, and the tourist shops do provide a bit of a respite in the long climb to the top. I too bought a “little something” (or two) from some of those shops, and although a number of them are tacky (I’m thinking snow domes for a start!), some have some really nice things, very much in the “must have” souvenir category that you can still live with back home, such as your bikky tin!