MONET’S HOUSE AND GARDEN: VISITING GIVERNY

I am often asked by friends and colleagues for suggestions for day trips out of Paris. There are so many destinations and great things to see and do, it’s a case of, “well, what are you interested in” or “how many trips do you want to do?” One destination that comes up more than most is Monet’s house and garden at Giverny. Even for those who aren’t necessarily keen gardeners, Giverny has the well-deserved reputation of being one of the loveliest experiences of a trip to France. Although many people take an organised tour from Paris, it is very doable under your own steam. The upside of doing it yourself is that you can spend as much time as you wish, sitting quietly on a seat in the garden or strolling at your own pace, which feels like taking a walk through a Monet painting.

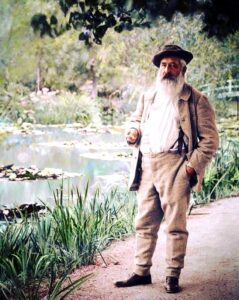

Claude Monet, one of the founders of Impressionism, chose not to attend the École des Beaux-Arts and instead, learned from the numerous established artists with whom he socialised. Eugene Boudin, in particular, was a great influence, especially as he introduced Monet to the then-unique idea of painting in the open air, that Monet adopted for the rest of his life.

When he was finally financially stable after years of struggle, Monet purchased a house just outside the town of Vernon, that he’d first spied from a train window. He moved there with his family to Giverny in 1883. The pink stucco house, that typical of the era had grey shutters when he bought it. Monet soon painted them a colour that the local villagers called “Monet green.” Originally, the house was called the House of the Cider Press, since an apple press located on the little square nearby gave the location its name. The house was much smaller than Monet’s needs, and he enlarged it on both sides, so it’s now 40m long although still only 5m deep. It’s easy to spot the new wings, as the windows are broader than those of the central part of the building.

Ten years after his arrival in 1893, Monet purchased a piece of marshland adjacent to his home to build a water garden, and much to his neighbours’ chagrin, even diverted a stream, the Ru, an arm of the local Epte river, to fill his pond and support the water lilies that would flourish here. The reason for the locals’ objections was that they were afraid Monet’s strange plants would poison the water. The first lilies arrived in 1894, and Monet nurtured and added to the plants and trees that surrounded the pond and his property, which fuelled his impressionist vision for over 30 years.

To say that Monet was obsessed by plants and flowers is something of an understatement. He employed a team of 6 gardeners, and spent the extraordinary sum of 40,000 francs per year on his obsession. By the end of the 19th century, Monet focused his art almost solely on his water garden and envisioned a series of large canvases that would cover the walls and envelope the viewer, “giving the illusion of an endless whole, of a wave with no horizon and no bank.” From the time he established the garden until his death in 1926, Monet produced nearly 300 magical canvases on the theme of the water lily pond and the surrounding gardens.

When you’re in Paris, if you’ve not seen them before, head to the Musée de l’Orangerie at the end of the Tuileries overlooking Place de la Concorde, to see the 8 enormous panels of the water lilies series, ‘Les Nymphéas’. These breathtaking paintings capture Monet’s representation of the shifting light and colour at different times of the day, and looking at them draws you in, making you feel as though you are immersed in the pond itself. It adds another dimension to a visit to his garden and lily pond at Giverny. He famously remarked that “My only virtue is to have painted directly in front of nature while trying to render the impressions made on me by the most fleeting effects.”

There are two parts to Monet’s garden. A flower garden, called Clos Normand, in front of the house, and a Japanese-inspired water garden on the other side of the road. The two parts of the garden contrast and complement each other.

When Monet and his family first settled there, the piece of land sloping gently down from the house to the road was planted with an orchard and enclosed by high stone walls. A central alley bordered with pines separated it into two parts. Monet had the pines cut down, keeping only the two yew trees closest to the house to please his wife Alice. From this Clos Normand of about one hectare, Monet made a garden full of perspectives, symmetries and colours.

The garden is divided into flowerbeds, where clumps of flowers of differing heights create volume. Fruit trees or ornamental trees dominate the climbing roses, the long-stemmed hollyhocks and the coloured banks of annuals. Monet mixed the simplest flowers, such as daisies and poppies, with the rarest varieties. The central alley is crossed by iron arches on which climbing roses grow. Other rose bushes cover the balustrade along the house.

At the end of summer, nasturtiums cover the soil in the central alley. Monet did not like organised or constrained gardens. He grouped flowers according to their colours and left them to grow freely. With the passing years, he developed a passion for botany, exchanging plants and cuttings with his friends Clemenceau and Caillebotte. Always on the look-out for rare varieties, he bought young plants at great expense. “All my money goes into my garden” he admitted, but added “I am in raptures.”

In the water garden you’ll find the famous Japanese bridge, painted the “Monet green” colour, covered in wisteria. There are weeping willows dipping into the water, bamboo, ferns, Japanese maples, rhododendrons, and above all, the nymphéas (water lilies), that bloom all summer long. The white water lilies are local to France, while the yellow, blue and a white that turns pink as it ages, are from South America and Egypt.

The pond and the surrounding plants form an enclosure separated from the surrounding countryside. This bridge is the second one. Monet had the first one built for him by local craftsmen. It had fallen into decay and was too damaged to be saved by the time the garden underwent its massive restoration, which took ten years from 1977. The wisterias however are those that were planted by Monet. From 1892 until his death in 1926, Monet produced nearly 300 magical canvases on the theme of the water lily pond and the surrounding gardens.

When you reluctantly leave the pond area, you will wander past Monet’s glorious gardens to his home. Once inside, visitors can visit each room. At one end of the house, Monet designed a large kitchen, suitable to prepare the meals of a ten person family that entertained a lot. Above the kitchen, Monet’s four step-daughters had their bedrooms, while his two sons and his two step-sons slept in the attic. The house has three entrances. The left one leads to Monet’s apartment, the middle one is the main entrance, and the right is for domestic use and leads to the kitchen.

Needless to say, Monet chose all the colours in the house. The best place to start your tour is probably the little blue salon, or sitting-room, a favourite place where Alice Hoschedé-Monet used to like to sit with her children. The stunning blues of the sitting-room, on the walls and on the furniture, harmonise with the Japanese woodblocks of Hokusai, Hiroshige and Utamaro that Monet collected passionately for 50 years. He ultimately owned 231 of them, and often said he loved having them around, as he found them inspiring. On the floor, cement tiles were very fashionable in Monet’s day.

The bright and cheery yellow dining room has Monet’s collection of blue and white porcelain on display, along with some more of his collection of Japanese prints. Sadly, these prints have lost some of their colour after being displayed in the light for so long, but we can imagine this room in Monet’s day, filled with colour, good food and wine, chatter and conversation. The blue and white theme continues into the kitchen with Delft wall tiles that are the perfect backdrop to show off Monet’s own gleaming collection of copper pots. Nearby is a small room that Monet fitted out as a pantry. It was unheated to enable the storage of food, especially eggs. It would seem lots of eggs were eaten, as the boxes hanging on the wall could store 116 eggs.

On the ground floor is Monet’s first studio. This later became his smoking room where he welcomed his visitors, art dealers, critics and collectors. On the walls, reproductions of his works evoke the atmosphere of Monet’s times. He liked to keep a record of each step of his career. Many of the originals that were kept in this room are now in the Musée Marmottan-Monet in Paris, one of our absolute favourites in the city. To read more about this beautiful museum, check out a blog story I wrote not so long ago: https://parisplusplus.com/paris/the-musee-marmottan-monet-a-little-known-gem-in-paris/ As with the rest of the house, the furniture and the objects are still exactly the same, which gives the house a great sense of authenticity.

Up a steep staircase leads to Monet’s bedroom. He slept in a very simple bed, and it’s the same bed where he died on 05 December 1926. He had gorgeous views onto the garden from the room’s 3 windows. He hung paintings by his Impressionist friends and colleagues such as Cézanne, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Morisot, Boudin, Manet and Signac.

As was typical of the upper middle class at the time, Monet and his wife Alice did not share a bedroom. Her very simple room is decorated with Japanese woodblocks featuring female characters. It is one of the few rooms that has a window on the street side of the house. The final room upstairs is the bedroom of Blanche Hoschedé-Monet, Alice’s daughter with her first husband, who lived at Giverny until her death in 1947. She was also Monet’s daughter-in-law, having married his eldest son Jean.

Monet’s large second studio, the so-called Water Lilies Studio was home to these vast paintings. Although it’s something of a pity that this huge space of over 300 sq.m. didn’t remain in its original state, it’s now the official gift shop selling a very good range of gifts relating to the Impressionist’s work, including books, scarves, tableware, posters, seeds and more. You won’t leave empty-handed.

When Monet died in 1926 of lung cancer, the entire estate passed to his son Michel. As he never spent time in Giverny, it was left to Blanche Hoschedé-Monet, Jean’s widow, to look after the garden with the help of the former head gardener. After Blanche died in 1947, the garden was left untended. Michel Monet died heirless in a car crash in 1966. He had bequeathed the estate to the Académie des Beaux-arts.

From 1977 onwards, Gerald Van der Kemp, then curator at the Palace of Versailles, played a key role in the restoration of the neglected house and gardens, which were by then in a sad, desolate state. He and his wife Florence appealed to American donors, who donated almost all of the $7 million needed for the restoration work, through the Versailles Foundation-Giverny Inc., and from then on they dedicated themselves to its restoration. Substantial work needed to be done. Floors and ceiling beams were rotting, furniture was broken and covered with mould, a staircase had already collapsed, windows were shattered, the garden almost in ruins and the Japanese bridge was rotting in black, clogged water. The Fondation Claude Monet was created in 1980 as the estate was declared public.

Before you go, head across the road to Restaurant Nympheas for a little refreshment. Also note that an easy stroll from the house is the village churchyard where Monet is buried. Also in the village is the Museum of Impressionism, showcasing work from Impressionist artists from around the world. However, if your time is short, perhaps pay a visit to the Musée Marmottan-Monet, or Musée ‘Orsay instead. The village also has plenty of cafes and restaurants.

Exploring the beautiful garden and wandering through the house, the visitor gains a real sense of personal ownership by the artist, his family and the friends who visited regularly. It is the home of a well-off painter, yet not in the least ostentatious or pretentious. A visit to Monet’s house and garden is a satisfying, enjoyable experience that stays with the visitor long after departure—a sentiment that cannot be felt in even the best museum.

Getting to Giverny from Paris is easy. From Gare St Lazare (just behind Au Printemps dept. store), take the train to Vernon-Giverny, which depart every hour or so. Note: you are taking a train that is going to Rouen, with stops along the way, so when looking at the indicator board at the railway station, look for departures to Rouen, not Vernon. The journey takes around 50 mins. At Vernon (along with many other people aiming to go where you’re headed), in front of the station are the shuttle (navette) buses to Giverny that are co-ordinated with the train schedule. It is a little too far for comfort to walk there from the station. When the bus arrives at Giverny, check the posted timetable at the bus stop for return times—these are also coordinated with the train timetable.

The house and garden are open daily from 09.30 – 6.00pm. Purchase your ticket for Monet’s house and garden in advance. Cost is around 12 Euros. It is a huge waste of time to try and buy it once you’re there, and you may miss out. If you do a quick Google search, you’ll find various websites that sell tickets, such as Ticketmaster and fnac, as well as those companies that offer bus tours from Paris.

“My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece.” Claude Monet

Leave a Reply