DEAUVILLE, THE RIVIERA OF NORMANDY, AND COCO CHANEL

Just 2 ½ hrs from Paris by train, Deauville is a favourite destination for many well-heeled Parisians looking for a weekend getaway. It’s often referred to as the Queen of the Normandy coast, ‘Paris-sur-Mer’ or the Kingdom of Elegance. Notable for its long sandy beach, beautiful Belle Epoque hotels, casino and racecourses, Deauville has been a playground for the rich and famous since the mid 19th century. There was a second wave of development at the turn of the century, and Deauville became a favourite resort with the “fast set” including the dashing English polo player, ‘Boy’ Capel and his mistress, Coco Chanel. She was quick to see the town’s potential for the leisured classes to indulge themselves further with some retail therapy, and opened her first shop here in 1913, marking the beginning of her fashion empire. Deauville has also been the background for countless films—the infamous Lord Lucan was once screen tested for the role of James Bond here!

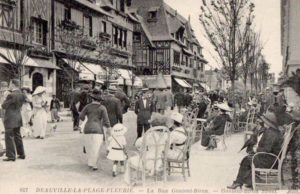

Deauville is situated on the Côte Fleurie in the Calvados Departement of Normandy. It was once a small agricultural village perched on a hill overlooking the sea, opposite Trouville, across the Seine estuary from Le Havre. Grouped around the 12th century church of Saint-Laurent, the hundred or so residents of “Dosville”, as it was known then, were, for the most part, farmers, and animal breeders. The marshland and dunes below the village, on which Deauville would later be built, were used by the locals for sheep and cattle grazing.

During the summer of 1858, the Duc de Morny, a wealthy, worldly financier and half-brother to Napoleon III, visited nearby Trouville to stay with his friend and physician one Dr Olliffe. During his stay, De Morny conceived of the idea of developing the expanse of swamp and sand into “an elegant kingdom”, as he called it, within easy distance of Paris. In partnership with Dr Olliffe, a banker named Donon and an architect, Desle-François Breney—said to be the best in Paris—de Morny acquired 200 hectares of land and 3km stretch of sandy beach facing Trouville, and created in just 4 years a town whose magnificent Anglo-Norman timber-framed grand hotels and villas, racecourse, and rail link to Paris, designed to attract a wealthy, aristocratic clientele.

These founders then established a real estate company and a local bank in 1863-64, but despite their considerable achievements, they were not to complete their goal as de Morny died in 1865, the Franco-Prussian war began, and the Second Empire fell in 1870. Although the Deauville project was still unfinished, nevertheless the railway connection to Paris had been laid, the construction of the Hippodrome de Deauville-La Touques was completed in 1862, and many luxurious villas built.

The Deauville Polo Club, founded in 1907, had become a magnet for wealthy fans of the sport, thanks to the influence of its founders Baron Robert de Rothschild and the club’s first President, the Duc de Gramont. They ensured that the club welcomed the most important members of European and British aristocracy. It was a location that was ripe for further investment.

1911 was an important year for the development of Deauville. That year saw the construction of its casino, the sumptuous Monte Carlo-style Barriere de Deauville, designed by Georges Wybo, the same architect who designed Printemps department store in Paris. Its Anglo-Norman architecture includes half-timbering, dovecots, turrets, gables and a décor that resembles a cosy but stately English country house.

In 1913 Wybo also designed Deauville’s Hotel Royal. A number of other luxury hotels were also built, ensuring that discerning Parisians and an international smart set couldn’t resist Deauville’s charms. By 1923, elegant holiday-makers paraded along the new 643 metre timber promenade that borders the vast beach.

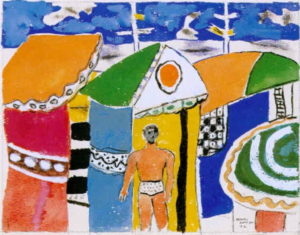

Famous faces such as cabaret stars Josephine Baker, Mistinguett and Maurice Chevalier, musicians, writers and artists including Sacha Guitry, Gustave Flaubert, Colette, Eugene Boudin, Raoul Dufy, Camille Saint-Saens and Arthur Rubinstein, the era’s greatest names from business such as André Citroën, royalty, Heads of State, and of course Chanel, were all regular visitors to Deauville.

Since the 1920s Deauville has been the location for a many films including ‘A Man and a Woman’, Agatha Christie’s ‘Murder on the Links’, and books including Marcel Proust’s ‘A La Recherche du Temps Perdu’ (a combination of Deauville and nearby Cabourg were the inspirations for the fictional town of Balbec), F. Scott Fitzgerald’s ‘The Great Gatsby’ as a place where Tom Buchanan and Daisy visited on their honeymoon, and the magnificent casino was the model for Ian Fleming’s first James Bond novel, ‘Casino Royale’ published in 1953. Georges Simenon’s early ‘Maigret’ stories were set in Deauville, and the English author, Ford Maddox Ford, lived his final years there and is buried in the town cemetery.

In 1913, the Normandy coast with its expansive grey-blue skies and long, sandy beaches still resembled the representations depicted by Eugène Boudin and the Impressionists at the turn of the 19th century.

There was no swimming, or very little at most; visitors splashed about in the shallows or baited for shrimp, and the more elegant among the visitors were seated decorously under their parasols or sheltered from the sun in their canvas beach tents, wearing the same restrictive outfits on the sand as they wore in town. They were unaware that a revolution was underway.

1913 was the year that Gabrielle (‘Coco’) Chanel opened her first fashion boutique, ‘Gabrielle Chanel’, on rue Gontaut-Biron (now rue Lucien Barriere) in Deauville, between the casino and the Normandy Hotel. The shop was only possible courtesy of the financial backing of her lover, ‘Boy’ Capel, who had become a director of the Deauville Polo Club in 1912.

Fiercely independent, it was important to Chanel that she repaid him as soon as she could. She had been born in Saumur in the Loire into abject poverty and abandoned at 12 to be raised in an austere convent where she learnt to sew. Throughout her life, she was obsessively determined never to be poor again, and never to sacrifice her independence.

Mademoiselle Chanel, who had successfully opened her millinery shop in 1910 called “Chanel Modes”, located at 21 rue Cambon in Paris, winning over the most elite socialites of the time. However, it was in Deauville where she was the first to invent a sporty sense of style that reflected a changing society, a style that would forever alter the course of women’s fashion history.

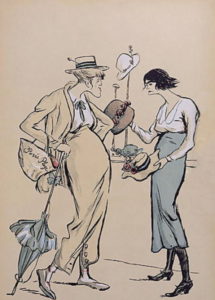

Here at this chic resort destination, she initially sold just her popular wide-brimmed hats that were simply decorated with a single feather or ribbon. Yet most importantly, she started offering wealthy clients an entirely new concept of day-wear apparel suited to an active life in the outdoors.

Once the beachside boardwalk, Le Chemin des Planches, was built in 1921, Chanel would use it to have models such as her young aunt Adrienne and her sister Antoinette, wearing a selection of her latest designs sauntering along its length, back and forth, to tempt her potential customers into her boutique. The shop became so successful that fashionable ladies would crowd outside waiting to gain entry. One local newspaper described Chanel, somewhat patronisingly, as ‘La Marchande de Frivolitiés’.

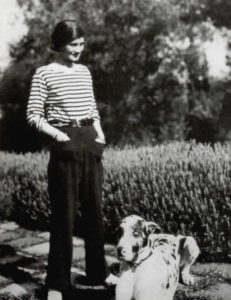

Her radical, first collection included the fishermen’s striped jersey sweater, la marinière, that was to become a much-copied eternal classic, defying time, and the vagaries of fashion movements ever since.

La marinière was first worn by quartermasters and seamen in the French Navy in the mid-1800s. Many sailors in the French Navy were from Brittany and Normandy. Their striped tops became known as Breton jerseys, and even today, la mariniere is described as having ‘breton stripes’. One of the original markers of la mariniere, Saint James, is still located in Normandy, very close to the Breton border. Saint James’ jersey cloth manufacturing tradition goes back to the 1100s, and they became an official supplier of marinières to the French Navy in the mid-1800s—indeed, they still supply these sweaters to the French Navy to this day.

Chanel saw fishermen on the beaches wearing their long-sleeve striped shirts and began wearing them herself. The Navy uniform mariniere could be tucked into men’s trousers and kept them warm all the way to their thighs. She redesigned and adjusted the proportions of the sweater to be suitable for womenswear, and it was ground-breaking for two reasons: it was the first time humble work-wear had entered the fashion scene, and the casual, loose design was a total rejection of the multi-layered, heavily corseted silhouette, as well as cumbersome hairstyles, imposed by the Belle Epoque. In retrospect, la mariniere and Chanel’s first collection has been hailed as nothing less than an emancipation of women’s bodies. By using simple jersey fabric, which until then had been used primarily for hosiery and men’s underwear, and considered too “ordinary” for high fashion, it was also very much in keeping with Chanel’s practical attitude to adapt this fabric during times of privation and materials shortage with the onset of WW1.

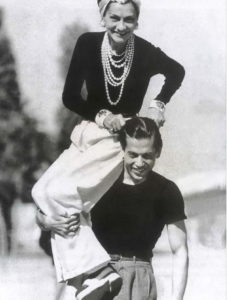

Other garments followed, embodying a casual chic that instantly put everything else out of fashion: la marinière was paired with sailor pants (which were sometimes called ‘yachting’ pants) or pleated skirts. This new look also included soft, cardigan-style jackets, polo shirts, jodhpurs, and famously, beach pyjamas that she accessorised with pearls (both fake and real), and silk camellias loosely stitched to the belt or collar lapel.

These were clothes that had never been seen on women before, who every day were hobbled in cascades of silk, secured by a million tiny hooks, stuffed into the tightest, whale-boned Casaque jackets over lace bodices with high, boned collars and double ruffed sleeves.

Although many were shocked by Chanel’s radical designs, they created a sensation among the overdressed (and probably overheated) ladies—exactly the reactions Chanel expected—and Deauville, where high society came to relax and play, was the perfect environment in which to launch her new fashion concept. Chanel once said ‘nothing makes a woman look older than obvious expensiveness, ornateness, complication’.

Chanel had anticipated the coming of a new era where women would eagerly adopt a new way of dressing to complement their more active, outdoor lifestyles that included swimming, horse-riding, skiing, tennis, and yachting. She created a wardrobe that would become known as “sportswear”, not because other women played sports, she said, but because she did, and declared that with her new fashions, “I restored the freedom of women”. Her ‘sportswear’ in the Deauville boutique reflected this revolution in how women’s relationship with their bodies was changing, along with their way of life and leisure pursuits. In the outdoor environment of turf, sea and sunbathing at Deauville, Chanel also made suntans not only acceptable, but a symbol denoting a life of privilege and leisure.

“Simplicity is the keynote to all true elegance.” Coco Chanel.

She breathed much-needed fresh air—indeed new life—into fashion, fully embracing the spirit of the times, which the Avant-gardists were also doing at that time in such areas of the arts as painting, sculpture, literature, and music.

The success of Chanel’s boutique had an impact on the reputation of Deauville as a resort for the international smart set soon inspired numerous Parisian stores to establish branches in the town. Printemps department store opened its first store outside Paris in Deauville in 1912.

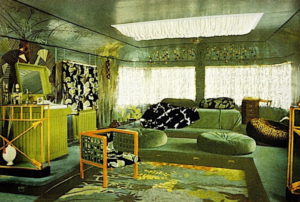

Following hot on its heels, Parisian fashion designer Paul Poiret opened an interior design business, La Maison Martine, selling a range of items ranging from carpets, glassware made in Murano, lighting, wallpapers, and other décor pieces, not only for the home but also private cruise boats. Other fashion designers such as Madeleine Vionnet, Jeanne Lanvin, Chanel’s arch-rival Elsa Schiaparelli, and Jean Patou all sent models and a selection from their collections to parade on Les Planches—an acknowledgement of the incredible success of Chanel’s idea. In 1924, Patou opened a specialised sportswear boutique called “Le Coin des Sports” in Deauville, and like Chanel’s sports and leisurewear, much of it was made from jersey knit fabric.

An obvious extension of the fashion world was the luxury jewellery houses. In 1912, high-end Parisian jeweller, Van Cleef & Arpels, was the first to open up what they called a “salon” in Deauville. They didn’t have the resort to themselves for much longer. News of their success soon spread, and not unsurprisingly, one of their Parisian competitors, Lacloche et Cie, opened a branch there in 1923. It didn’t take too long for others joined them.

Deauville had a number of venues where the wealthy leisured visitors spent time, one such was of course the casino. Today it’s easy to find, located beside Place Yves Saint-Laurent, commemorating the designer who had a house in Deauville.

One of the favourite pastimes of the wealthy visitors to Deauville was horseracing, and it’s still true to say that in Deauville, the horse is king. Behind the town are the two racecourses, Hippodrome Deauville La Touques and Hippodrome Deauville Clairefontaine. Since the town’s beginnings, horseracing has been a major part of life here. Flat racing takes place all year-round, while in August, 3 polo pitches host international sides in matches.

The town is inseparable from many equestrian events and activities aside from racing. Throughout the year there’s show jumping, horse auctions, and international meetings, you can take a ride through town in a traditional carriage and enjoy unforgettable rides along the beach. If you’re an early riser, you can watch the racehorses exercising on the beach first thing in the morning.

A must-see for anyone interested in the history of Deauville is a visit to the Villa Strassburger. The grandest house of the Belle Époque, built in 1907 by Henri de Rothschild, it was bought by American newspaper mogul and racehorse owner Ralph Strassburger in 1924. The entire villa, which was donated to the town in 1980 by Strassburger’s only son, is kept just as it was in the 1920s and ‘30s and is classified as a Monument Historique.

Fine chintz-covered furniture sits alongside gramophone players and Bakelite telephones, and upstairs, a huge, black vacuum-cleaner squats ominously on the landing. There are a number of framed pen-and-ink cartoons from contemporary magazines that show the style in which Strassburger enjoyed life in Deauville. You can see him frolicking in the sea with the likes of Edith Piaf and the Aga Khan, enjoying champagne with singers Juliette Gréco and Maurice Chevalier. Take a particular note of the green-tiled bathroom, with its oversize shower and walk-in sauna. This entire room was installed by the Nazis, whose local commander occupied the villa during the Occupation, and also had an underground bunker built at the back of the house. Visits from June to Sept.

Along with most of the other luxury villas of Deauville, the enormous Belle Epoque villa that Andre Citroen rented for the summer each year, ‘Les Abeilles’ (The Bees), was also taken over by German officers during the Occupation.

Whether or not you like to gamble, it’s worth popping into the Casino Barrière de Deauville. The beautiful façade, with its majestic high windows and elegant entrance hall has been designed to feel like a royal palace—crystal chandeliers, high ceilings and lots of regal red and gold décor in the parlours and lounges.

The casino also has a stunning theatre, although it’s referred to as the Italian Theatre, it’s said to have been inspired by the theatre at the Palais de Versailles with its oval shape, large horseshoe-shaped balcony, punctuated with tall, fluted timber columns and elegant décor.

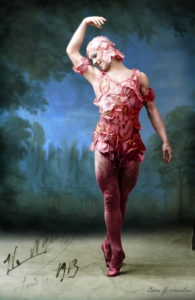

For the casino’s inauguration in 1912, the theatre’s first performance was by the Ballets Russes, whose star Vaslav Nijinsky performed ‘Le Spectre de la Rose’. Chanel collaborated on productions choreographed by Diaghilev Nijinsky and composer Igor Stravinsky for the Ballets Russes over many years up until 1937.

The ’Pompeian Baths’ are certainly something to see! Designed by Parisian architect Charles Adda, who was responsible for Les Planches boardwalk, built this structure in 1923, replacing the original beach cabins which had deteriorated and no longer considered appropriate for the increasingly fashionable resort town. Although its design is typical of the Roaring Twenties, Adda used ancient Roman bath complexes as his inspiration, complete with beautiful mosaics. Built around nine courtyards, it has 50 shower, massage and steam rooms as well as swimming pools, an American bar, a hairdresser and shops.

Chanel could see the possibilities with the popularity of the new Baths and the improvements to the beachfront, and used Les Planches promenade as an outdoor catwalk as soon as it was completed. Other designers soon copied her idea. We’re very used to promotional and marketing techniques such as this, but until Chanel did it, it had never been done before. It’s now listed as a Monument Historique.

The story of Deauville cannot ignore its 1930s Depression and wartime experiences. The aura of a hedonistic paradise died completely and wouldn’t resurface until the 1950s. During the war, the German Army occupied Deauville, and luxury villas, hotels and the casino were all occupied or used by them, until Operation Overlord—the D-Day landings—was launched on 06 June 1944 on the coast of Normandy. Deauville was one of the towns that suffered the most damage during this operation, due to its occupation by the Nazis. Chanel had seen the writing on the wall and closed all her shops, including the Deauville boutique, in 1939.

Deauville’s fortunes were on the rise from 1951 when every August, the town welcomed the ultimate playboy of the time, the Dominican sporting diplomat, Porfirio Rubirosa. With his good looks, athleticism and irresistible charm, he attracted Hollywood film stars and together with his own polo team, international polo competitions were revived.

Over the years Deauville has enlarged its cultural landscape. Said to be the biggest French film festival after Cannes, the Deauville American Film Festival was created in 1975 to promote independent American cinema in France. Nearly 100 films are screened each year for 10 days in early September and is the only European festival of this scale to be open to the public. More recently, an annual Asian film festival has begun.

There are 2 classical music festivals, the Easter Festival and Musical August, a jazz festival, Swing’In Deauville in July, and a Books & Music fair in May, as well as plays concerts, dance and recitals at the Deauville International Centre and the Barrière Casino throughout the year. July also has the Deauville Classic Week with the French Open Dragon Boats and a World Bridge Festival, and if you’re around in October, it’d be fun to time your visit to catch the Paris-Deauville Rally for classic cars.

For a change of scene, the lush countryside in this region has an abundance of trees and orchards from which come the half-timbered houses typical of the region. And, of course, there’s food: apples (think Normandy’s famous cider), some of the best butter in France, cream, rich cheeses and high quality meat. This is a place to abandon any thoughts of dieting!

Deauville is a great base from which to explore other picturesque villages, towns and sights nearby, such as Villerville, Trouville-sur-Mer, Cabourg, Honfleur and perhaps even a little further afield to Falaise, birthplace of William the Conqueror. Perhaps I’ll look at some of these in greater depth some time soon.

We are both amazed at your meticulous research particularly on this very informative blog! It is certainly a tease and real motivation to get back over to see this and your other areas of interest.

Annette thinks we might have to move there for 12 months, how is your booking schedule?

Dear Tony and Annette,

What lovely comments! I’m so delighted you enjoy the blogs, as I do writing them. We too are longing to be able to return to our favourite destination asap, and of course, you know you always have your little Paris home awaiting your return at any time. Yes, I think 12 months sounds like a great idea–we’ll meet you there!

Cheers for now, Cheryl

Dear Cheryl,

Thoroughly enjoy your most informative posts and particularly this one on Deauville. Think I would be very happy there in ‘Coco Chanel Land’. Must visit eventually…………one day! Rxx?

Dear Robbie,

Thanks so much for your response to the article. It is indeed a beautiful part of the country. It’s quite unlike other parts of France, esp. given the huge amt. of Belle Epoque architecture everywhere. Very special indeed. It’s right up there on our must-revisit list–and may that come very soon! It’s important to have something to look forward to.

xx Cheryl