A ONCE-FAMOUS LONDON COURTHOUSE NOW A CHIC HOTEL

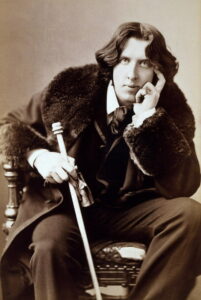

The latest London hotel everyone is talking about is NoMad, the first outside New York for the group that owns it. The interesting thing though is that it occupies the former Bow Street Magistrates’ Court and Police Station, a landmark historic building. It’s located opposite the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, and had been closed since 2006. It was the most famous Magistrates’ Court in England in the latter part of its 266 year existence, being the venue for such notorious cases involving high profile trials for the likes of Oscar Wilde, Giacomo Casanova, the Kray twins, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, Christine Keeler, and General Pinochet, among many other reluctant visitors.

Over its 266 year existence, the Bow Street Magistrates’ Court occupied various buildings in this street in Central London. The first court in Bow St. was established in 1740, when Colonel Sir Thomas de Veil, a Westminster judge, sat as a magistrate in his home at number 4. De Veil was succeeded by the novelist and playwright Henry Fielding in 1747, at a time when the problem of gin consumption and resultant crime was at its height. Fielding reported that every fourth house in Covent Garden was a gin shop, and in an attempt to tackle increasing crime, he brought together 8 constables, who became known as the Bow Street Runners, due to their efficiency and speed in the pursuit of criminals. Fielding was succeeded by his half-brother Sir John Fielding, “the Blind Beak of Bow Street”, who was reputed to be able to recognise 3,000 criminals by their voices.

The early 19th century saw a dramatic increase in the number and scope of the police based at Bow Street. In 1815 the Bow Street Horse Patrol was formed by Sir John Fielding, arming his men with truncheons, cutlasses and pistols, and in 1821 the Dismounted Horse Patrol was formed, which covered suburban areas. The Bow Street Runners disappeared when the Metropolitan Police Service was established in 1829, and a station house was soon established. However, it was clear that bigger premises were needed and in 1876 the Duke of Bedford leased a site to the Commissioners of HM Works and Public Buildings for a new magistrates’ court and police station. The current building was commenced in 1878 and completed in 1881—the date 1879 above the door of the present building was the date it was hoped that work would be finished. The adjoining police station, built in a similar Greco-Roman style, was completed at about the same time.

In its later years, the court housed the office of the Senior District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) who heard high-profile matters, such as extradition cases or those involving prominent public figures.

About 1760, the infamous libertine, Giacomo Casanova, appeared in Sir John Fielding’s court, accused of assaulting a prostitute and was bound over to keep the peace; in Charles Dickens’ ‘Oliver Twist’ he has the Artful Dodger appear in the court in 1838; in 1895 Oscar Wilde was in the dock after his arrest for “committing indecent acts”, and was sentenced to two years’ hard labour.

Suffragettes Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst and Eve Haverfield appeared in the court in 1908 and were jailed for handing out leaflets urging their supporters to “rush” the House of Commons; around 1910, Dr Crippen, who had murdered his wife Cora and fled to Canada, was captured and returned to London, whereupon he appeared at Bow Street, was tried at the Old Bailey and hanged; D.H. Lawrence’s novel ‘The Rainbow’ was declared obscene by a Bow Street magistrate in 1915.

In 1945, Nazi propagandist William ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ Joyce appeared in the court on high treason charges and became the last person to be executed for treason in the UK; The East End gangsters, Ronnie and Reggie Kray appeared in Bow Street after a series of dawn raids by police and charged with conspiracy to murder two other underworld characters. In 2000 Tory peer and author Jeffrey Archer was committed for trial on charges of perjury and perverting the course of justice. The iconic fashion designer, Vivienne (later Dame Vivienne) Westwood once spent a night behind bars for Breaching the Peace following a fight with police over a noisy boat party in 1977, organised by her partner Malcolm McLaren and his punk band, the Sex Pistols.

There were also those facing extradition proceedings who appeared in the Court. In 1999 former Chilean leader General Augusto Pinochet was excused from attending his extradition hearing at Bow Street due to ill health. James Earl Ray, convicted for assassinating Martin Luther King Jr. and had been on the run since, was captured in the UK and extradited back to the USA.

The Bow Street Magistrates’ Court was particularly familiar to members of The Rolling Stones, with 3 bandmembers being tried there over a 5 year period on charges of possession of cannabis. Mick Jagger and his then-girlfriend Marianne Faithful were in court over their arrest for cannabis possession following a raid on their Chelsea home. Jagger was fined 200 GBP and made to pay 50 guineas costs, although the charges against his girlfriend were dismissed. Keith Richards was fined at the court on drugs and firearms charges in 1973.

The police station shut up shop in 1992 and the magistrates’ court heard its final case in July 2006. Since its closure, the Grade ll listed buildings were on the Heritage at Risk Register. After passing through the hands of various developers, the two buildings were sold to the UK arm of Qatari investment firm BTC in 2016. It set about turning the Grade ll-listed Victorian police station and magistrates’ court into a luxury, 91-room hotel for the New York-based NoMad chain—its first in Europe. Those in the know all agree that the hotel has successfully translate the brand’s sophisticated-casual New York style to London.

At the centre of the building is a large, glazed courtyard that was the key to the scheme being able to accommodate many of the hotel functions critical to its success. This pistachio-green, plant-filled courtyard space houses the hotel’s main restaurant, NoMad, one of the hotel’s five restaurants. The menu centres around a wood-burning grill and farm-fresh, UK-sourced ingredients.

Beneath the courtyard and the newly constructed guest-rooms extension is a newly created, three-level basement, the upper level of which houses the gym, giant atrium restaurant, and three large kitchens, with associated storerooms and preparation spaces. Under this, on basement level 2, are the back-of-house spaces, including uniform dispense space, locker rooms and staff canteen. This level also includes the top half of a double-height plant space, the lower half of which forms basement level 3.

The remaining rooms and larger suites are in the existing heritage buildings, with some of the former cells and custody spaces enlarged and converted into hotel rooms by removing separating walls.

What made the heritage aspects of the new scheme particularly awkward was that the magistrates’ court and police station had been built independently of each other, so their floor plates were not aligned.

Much of the original building fabric was retained and celebrated: the courtroom is now an event space, and the scheme incorporates a public museum telling the story of the buildings, complete with prison cells.

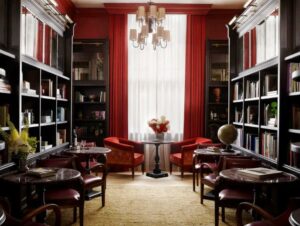

There’s a lively pub, Side Hustle, servicing British and American spirits alongside Mexican fare in the court’s former police station. The Library, a refuge for all-day snacks and drinks, blends books and artwork representing both cities—particularly their shared love for theatre, as those enjoying a coffee, tea or cocktail on its red velvet furniture will find themselves sitting just across the street from the Royal Opera House.

Common Decency, NoMad’s intimate subterranean bar, is where East London cocktail bar meets West End nightclub. There’s live entertainment, and private booths at the rear are nestled into Victorian-era coal holes once used to heat the building.

For private dining and events, including weddings, the former heart-of-the-action, the Magistrates’ Courtroom, is now a beautiful ballroom with two dining rooms, a bar and its own entrance.

The hotel’s décor is a mix of Victorian flourishes and New York’s Jazz Age. There is an impressive selection of artwork, which ranges from contemplative post-war items to contemporary works. The 91 guest-rooms have a selection of colourful abstract art with a clever blend of Victoriana, Art Deco frivolity and 20th century modernity in the fixtures and furnishings, including custom-blown glass lighting, gilded wardrobes, old-fashioned telephones, cute minibar cabinets and velvet studded chairs. The smallest room category may well be the coolest: down a light green hallway, what was once the women’s gaol wing is now a hall of guest rooms (two cells making a room), with the original tilework and cell doors still intact.

There is no pool, but instead, there’s an elegant spa centre and Pilates Studio.

The adjacent Bow Street Police Museum opened in 2021 is located in the former police station. The museum galleries area situated in the cells and offices of the former Bow Street Police Station, present the history of policing in the area from the mid-18th century to the closure of the police station in 1992. This includes the experiences of police officers, and of prisoners detained there pending appearance in the Magistrates’ Court next door. Exhibits include an original Court dock, equipment used by the Bow Street Runners, and personal effects of former officers, including beat books and truncheons. Visitors can enter a large cell called “the tank”, once used to detain overnight those arrested for drunken behaviour in Covent Garden. The stated aim of the museum is that when visitors walk through its doors, they will have a real sense of the history of Bow Street and the people who have passed through those doors before them.

Situated in the heart of London’s Covent Garden district, across the road from the Royal Opera House, the ornate white buildings of NoMad Hotel, the former Bow Street Magistrates’ Court and Police Station, is fast becoming a favourite haunt of locals, guests and visitors alike. This London hot-spot is the only 5 star hotel in the neighbourhood. Super-fashionable, very chic, yet its innovative transformation allows it to embrace its history as perhaps the most famous Court House in London. Next time you’re in London, go and check it out.

Leave a Reply