THE GREAT FIRE OF NOTRE DAME – FROM DISASTER TO MIRACLE

When news broke on 15 April 2019 that a fire had started to engulf the iconic Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, along with most of the world, we held our collective breaths as we sat, transfixed in front of the TV. The very thought that this wonderful building, which many regard as the true symbol of Paris, could collapse was almost too much to bear. We had been in Paris a few weeks before the fire and were due to return in May 2019, and we had mixed emotions, from dread at the sight of the appalling disaster to great curiosity and anticipation about seeing first-hand, the start of the massive stabilisation and conservation program that had been put in place with lightning speed.

Our first day back in Paris took us down to the river where we managed to find a space along the stone wall on the Left Bank. There was quite a crowd of onlookers, as well as people on their way to work, pausing just for a moment to pay their respects. The sight of such a cross-section of Parisian society, from well-dressed businessmen in suits, students en-route to class, side-by-side with visitors, mostly in silence, many with tears on their faces, was a small indication of the deep shock mixed with reverence for this pinnacle of civilisation that was almost lost forever. As someone remarked, Notre Dame was an expression of what it means to be human.

The story of the cathedral’s massive restoration is fundamentally about bravery, determination and phenomenal skills, uniting for the single aim of resurrecting this beloved building, the symbol for many of the City of Light.

One of the most interesting aspects of the restoration works were the large information posters attached to the cyclone fence surrounding the site. These had photos and stories about the craftspeople and their areas of expertise, and every time we returned to Paris, the posters had changed to feature different crafts and personnel.

The fire, which investigators believe was started by a cigarette or an electrical short circuit while repairs to the roof were in progress, took firefighters over 5 hours to extinguish. Miraculously, the bell towers, the stained-glass rose windows and 1,300 artworks were saved. The fire destroyed the cathedral’s timber spire (flèche), most of the timber roof and severely damaged the upper walls. The vaulted stone ceiling mostly contained the burning roof as it collapsed, preventing even further extensive damage to the interior.

As the cathedral burned, Emmanuel Macron, the leaders of the Senate and the National Assembly—the whole government—rushed to its side. At 9.30pm, Macron authorised the courageous, indeed daredevil, attempt by 150 firefighters to save the cathedral by attacking the fire from inside the north belfry. Never was the Paris firefighters’ motto “Sauver ou Perir” (To Save or to Die), more evident than on the night of 15 April 2019. As Jean-Claude Gallet, the 3-star general and commander of the Paris fire brigade said, “the situation was so grave, audacity was the only option.”

The embers were still hot when President Macron vowed that France would rebuild Notre Dame “…to be more beautiful than ever. Notre Dame is our history, our literature, our collective imagination, the place where we have lived all our great moments, our wars and our liberations. It is the epicentre of our life…the cathedral of all the French people…I am telling you now, solemnly, that we will rebuild her. We will call upon the greatest talents to contribute to her reconstruction…It is what the French expect of us, it is what our history deserves; it is, in the deepest sense, our destiny.”

The devastation was immense. The spire had gone, its collapse having destroyed part of the vaults near the crossing of the transept. The forest of lattice framework underneath the cathedral’s lead roof, made of a thousand oak beams dating from the 13th century, had turned to charcoal and dust. The lead roof had melted and evaporated. The water used to fight the fire had weakened the masonry and an army of sculptures and gargoyles now needed painstaking repair and in some instances, replacing. Everything else needed thorough dusting, cleaning and restoration, including all the pillars, stained glass, chapels, paved flooring. One of the biggest, and most daunting restoration projects was the more than 8,000 pipes of the magnificent grand organ, one of the largest in Europe. The task was herculean.

The skills and expertise that came together to work on the project was a tribute to the sense of determination and collective goodwill among all the workers, who ranged from the cleaners, skilled artisan craftspeople and highly qualified archaeologists and conservation specialists. Experts from all over the world volunteered their time and skills to advise and contribute to the project, although the majority were French. France is a country with an enormous collection of ancient structures such as cathedrals, town and village churches, châteaux and other monuments, and has a highly skilled population of artisans and professionals who have vast experience in working on these structures. Modern technology is mostly confined to things such as fire, safety and security measures. This was the policy applied to Notre Dame.

France has always valued its artisans, especially those perpetuating old traditions and skills. Known as the Compagnons du Devoir (Companions of Duty), they belong to an organisation dating back to the Middle Ages. Starting their apprenticeships at 15, they spend years touring France, learning their skills as they go from town to town assisting older, master artisans. They are taught not only a craft, but an ethic, with the motto: ”Neither self-serving nor submissive, but being of service.” On their shoulders rested the immense responsibility of rebuilding, as one remarked, “the Soul of France”—and in this instance, on a tight schedule. The thousands of artisans working on the site and in their workshops may have been the best, but the pressure of time must have been enormous. The French administration, instead of relying on a single contractor for the ambitious works, employed over 250 businesses, small workshops and niche experts.

One of the craftspeople working for the construction company, Cruard Charpente, located near Nantes, said in a TV interview: “For me, it’s important to repair old buildings, it is like nursing the injured. And I like using old techniques.” He has worked on the Louvre and the medieval market hall of Milly-la-Foret, near Fontainebleau, but continued to say that “working on Notre Dame is simply the chance of a lifetime.”

The sourcing of building materials was very specific, meaning that as much came from the original forests, quarries etc. as was possible. For example, the oak used for the dense latticework of beams and trusses mostly came from historic trees in the Bercé forest in the Loire valley, the same forest as the originals had done. The size of the lengths of timbers required was massive. For example, the huge lengths of oak for the tabouret, or base, of Notre Dame’s new spire required two diagonal beams 20 metres long, and came from eight oak trees. The spire base is 15 metres long, 13 metres wide and six metres high.

On the evening of the fire eight bells in the north belfry survived thanks to the dedication and determination of the 150 firefighters, who put out the flames attacking the timber structure supporting them. Had they failed, the north belfry would have crashed down on to the south tower, and then the whole cathedral would have collapsed like a house of cards. The eight bells, named Gabriel, Anne-Genevieve, Denis, Marcel, Etienne, Benoit-Joseph, Maurice and Jean-Marie, were taken to Cornille-Havard foundry at Villedieu-les-Poêles to be checked out. Fortunately, six of the eight only needed cleaning and waxing for harmonisation, two needed heat treatment and a bit of welding. A ninth bell, named Emmanuel, had been cast during the reign of Louis XIV and had been hanging in the south tower since 1686 and only required cleaning. Six bells were destroyed and had to re-cast.

One of the great landmarks in the restoration was the spire itself and the spire’s needle, (l’aiguille). Crowds gathered on the evening of its installation, where it was raised to a height of over 100m, and fixed to the top of the spire. Once in place, the 66 metre, coffee-coloured oak construction holding the spire was covered with hundreds of sheets of lead. In just eight months, it had all been carved from oak trees, put together and erected above the cathedral. Quite an achievement. They revived the original drawings from the mid-19th century installation by the architect Viollet le Duc.

Nine days before Christmas 2024, the final touch to the spire was the installation of Notre Dame’s new gilt bronze rooster before the scaffolding around it came down. With its flame-like feathers, it looks, rather appropriately, like a phoenix. At 4.00pm on a beautiful, sunny winter afternoon, the archbishop of Paris placed the relics of St Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris, inside the cockerel. After a short blessing, it was then lifted into the bright blue sky and fixed on top of the needle. It can be seen from kilometres away. On the night of the fire, the original weathercock had whirled into the air and the next morning it was found, battered and badly bruised, lying in the gutter of the little street than runs alongside the cathedral. It was too damaged to be restored, and it’s now on display in the Museum of Architecture and Heritage at the Trocadero.

The great thrill for us is that a young Canadian friend of ours, Emily MacKinnon, who is based in Paris, applied for tickets not only for herself, but kindly included us as well. All tickets were free, but the only way to obtain tickets for either of the first day Masses was online, and needless to say, the website was swamped. Our friend stayed on her computer all night, patiently re-entering the required data every time the application page timed out. She was ultimately successful, obtaining 3 tickets just a few hours before the 6.30pm Mass time. We shall remain forever grateful for her perseverance and determination! She is starting her own business as a freelance tour guide for Notre Dame. Her knowledge of the cathedral and its history is prodigious, she is a bright and engaging personality, and we know she will be a great success.

The interior is breathtaking. We were a little wary before we’d seen it, in case the massive cleaning and restoration that had taken place had removed much of its historic atmosphere, as patina carries an age value that reflects its historic identity. We have seen other restoration projects where the cleaning process has unfortunately eliminated much of its historic character. We need not have been concerned. Approx. 1,300 cubic metres of limestone were needed to restore the damaged walls and vaults. The original limestone quarries beneath Paris are no longer in use; therefore, stone was sourced from the Oise region in northern France and cut in Gennevilliers. The result is a bright, cream-coloured stone, achieved through a careful cleaning process to remove soot, pollution, fire damage and salts. This involved applying a paste of kaolin and clay to the stone surfaces, which was then peeled off to reveal the original material. The new stone blends perfectly with the restored original. The result is luminous.

The reconstruction of the nave and choir required 1,200 oak trees, many from the Bercé forest, and the rest from carefully selected forests across the country, with a number of private forest owners donating trees to the reconstruction project. Advanced digital technologies played a crucial role in the restoration, digitally recreating the cathedral from various scans, which took two months and involved six high-performance computers to process the data.

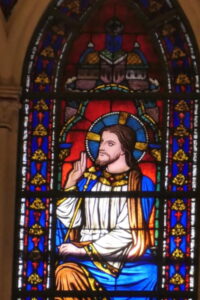

Enhancing the cleaned, luminous interior stonework are the beautiful stained glass windows. They are among the most famous features of the cathedral, particularly the three great medieval rose windows. Having been thoroughly cleaned, the colours of the original glass are vivid and clear. It was nothing short of a miracle that the glass remained intact—they were undamaged but filthy. In fact, the fire offered an opportunity to rediscover the glories that lay beneath decades of dirt and soot. All but the huge rose windows, which had to remain in place, were dismantled, removed, cleaned and returned. Blues, reds and golds have re-emerged, and combined with the creaminess of the rejuvenated limestone, create a lightness that must be much closer to the original experience.

One of the most memorable events of that first Mass was the sound of the 15th century Grand Organ. Miraculously, it survived the fire with minor damage, and sustained water damage in only one pipe out of thousands. However, it all needed to be totally restored to remove the lead dust that had settled inside. The instrument is approx. three stories tall, with over 8,000 pipes, with the largest standing an impressive 10m tall. Each had to be removed, cleaned and re-tuned. The sound is incredible! Towards the end of the Mass, the Archbishop walked to the centre of the main aisle, gazed up at the organ, and called “Awake oh organ, Let God’s praise be heard!” The cathedral vibrated when the organist struck the first chords, and the entire congregation rose to its feet and gasped. It was indeed a miracle. Fittingly, it was played by organist Olivier Latry, who was the last person to play the great instrument, on Palm Sunday 2019.

When you’re next in Paris, do make time to visit Notre Dame, and experience for yourself the wonderful sight of this remarkable building, brought back to life, more spectacular than ever, and resuming its place as the living symbol of the City of Light.

Fascinating. Glad you’re back online.