BARON HAUSSMANN: VISIONARY FOR MODERN PARIS OR VANDAL OF HISTORY?

The Paris we know today has only existed, in large part, since the mid-19th century. Before then, much of the medieval city was a dark, overcrowded and unhealthy place. The wide, tree-lined boulevards and fine, creamy stone buildings we enjoy and admire today are mostly due to one man, Georges-Eugène Haussmann. The dramatic urban renovation program undertaken by Haussmann was under the orders of Napoleon lll, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, a visionary and idealist, who was determined to transform Paris into a modern city fit for the new industrial era.

While living in England in exile in the mid-1800s, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte visited London, a city rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666. He was very impressed with the spacious streets, modern city planning, and hygiene. Throughout the Second Empire, he wished to make Paris a city as modern and prestigious as London. He found the perfect person in Georges-Eugène Haussmann to execute his grand ideas.

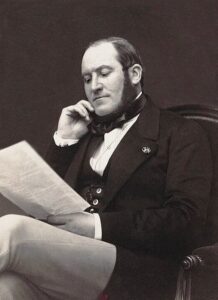

Descended from a Protestant family from Alsace, Haussmann had both paternal and maternal connections to the Revolution and Napoleon. His paternal grandfather had been a member of the legislative and conventional assemblies during the Revolution, while his maternal grandfather was a general during the time of Napoleon. Haussmann was born in Paris on 27 March 1809, in a house that he would later demolish during the huge works program.

Haussmann began his schooling at the College Henri IV and the Lycée Condorcet, and then studied law in Paris. At the same time, as a talented musician, he studied music at the Paris Conservatoire. He was married on 17 October 1838 in Bordeaux to Octavie de Laharpe, and they had 2 daughters, Henriette and Valentine. Haussmann joined his father as an insurgent in the July Revolution of 1830, which deposed the Bourbon king Charles X in favour of his cousin Louis Philippe, Duke d’Orléans.

Haussmann began his career in public administration, and was named the secretary-general of the prefecture of the Department of Vienne at Poitiers. In June 1832 he became the deputy prefect of Yssingeaux, but despite proving himself as a hard worker and able representative of the government, his arrogance, dictatorial manner, and habit of impeding his superiors led to his being continually passed over for promotion to prefect. Instead, he had numerous postings as deputy prefect of a number of Departments. Only after the 1848 Revolution swept away the July Monarchy, establishing the Second Republic in its place, did Haussmann’s fortunes change. Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, became the first elected president of France in 1848.

Haussmann travelled to Paris in January 1849 to meet the new Minister of the Interior and the new President. He was deemed to be a loyal member of the civil service that survived from the July Monarchy, and finally achieved promotions to two prefectures, the Yonne and later, the Gironde.

In 1850, Louis Napoleon stated an ambitious project to connect the Louvre to the Hôtel de Ville by extending the rue de Rivoli. He also wanted to create a new park, the Bois de Boulogne, but was exasperated by the painfully slow progress made by the incumbent Prefect of the Seine. At the end of December 1851, he staged a coup d’état and in 1852 he declared himself Emperor of the French under the title Napoleon lll. This move was given overwhelming approval by a plebiscite, and he soon began searching for a new Prefect of the Seine to carry out his Paris reconstruction program, and after interviewing many prospective candidates, chose Haussmann.

The new Emperor decided very quickly that Haussman was exactly the man he needed, and gave him the mission of making the city healthier, less congested and grander. Haussmann held this post until 1870. As Prefect, Haussmann wielded enormous power, which led one commentator to refer to him as the “vice-Emperor.”

Haussmann’s Mémoires portray him as a very serious, organised administrator, who preferred concrete, rational and feasible projects. For example, he had detailed accounts of the number of new gas lanterns compared to that of the oil lamps they were replacing, and the number of chestnut tees that were being planted along boulevards. His innate sense of discipline and his trust in proper administration as the main vehicle for social change made him the Emperor’s perfect partner in this massive project to renovate Paris. Napoleon lll’s great vision also included new, wide boulevards, parks and public works. The two men took on the transformation of what was essentially a medieval city into a modern capital.

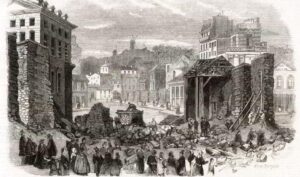

Napoleon lll and Haussmann hired tens of thousands of workers to improve the sanitation, water supply and traffic circulation of the city. The Emperor installed a huge map of Paris in his office, marked with coloured lines where he wanted new boulevards to be. This plan was not just to improve traffic flow. In the 19th century, central Paris was a spider’s web of narrow streets that could easily be barricaded with nothing more than the furniture from neighbourhood homes. Paris was under siege numerous times, not by a foreign army but its own people. Parisians couldn’t agree whether they supported dictatorships, democracy or something else, and by 1870, six different regimes were brought down by massive riots and rebellions.

A key element of the various revolutions was the very streets of Paris. With every uprising, cobblestones were ripped up and became missiles. According to one historian, the 1830 Revolution saw over 4,000 makeshift barricades erected, while the February Revolution of 1848 involved more than 6,000! These roadblocks were instrumental in deterring police forces and the military from quelling these uprisings, so Napoleon lll resolved to deal with this once and for all, before another revolution also brought him down. Enter Haussmann.

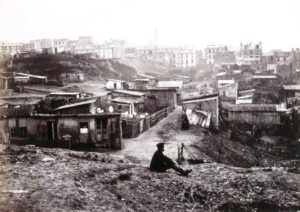

The overcrowding had become worse and worse as time went by, especially since the population of Paris had doubled since 1815, with no increase in its area. To accommodate the growing population and those who would be forced from the centre by the new boulevards and squares he planned to construct, Napoleon lll issued a decree annexing 11 surrounding communes and increased the number of arrondissements from 12 to 20, which enlarged the city to its modern boundaries.

Beginning in 1854 in the centre of the city, for over 17 years Haussmann’s workers tore down an estimated 19,730 buildings, according to one source. Many of those were located in the poorer neighbourhoods, which coincidentally, happened to be where much of the violent turmoil in the city took place. In what is now the 3rd arrondissement, there was one inhabitant for every 3 sq. metres—typical for the poorer neighbourhoods. Disease spread very quickly in these cramped, unsanitary conditions. Cholera epidemics ravaged the city in 1832 and 1848, when over 5% of the inhabitants of these areas died.

Haussmann would be the first to say that he was no architect. Rather, he described himself as an “artist-demolitionist”, so naturally, his preferred method of fixing the cramped neighbourhoods with their narrow streets was to knock everything down. He rarely visited the neighbourhoods that he destroyed, instead, barking his orders from the comfort (and no doubt, security) of his office was his favoured style. Napoleon lll described Haussmann as being “…one of the most extraordinary men of our time; big, strong, vigorous, energetic, and at the same time clever and devious, with a spirit full of resources.” To thank him for his work, in 1857 Napoleon lll created Haussmann a member of the French Senate and gave him the honorary title of Baron.

Haussmann saw himself as the “devoted instrument…the principal worker on this colossal project.” This remains the largest urban renovation project in Western European history. Eighty kms of new avenues were cut through Paris, connecting the central points of the city. Buildings along these avenues were required to be the same height, usually 6 storeys, and in a similar Neo-Classical style, and to be faced with cream-coloured stone, creating the uniform look of Parisian boulevards that we so admire today.

The ground floor usually accommodated shops, as did the 1st level, which had lower ceilings than the upper floors. The 2nd floor was intended for the upper classes—it’s where wealthy Parisians lived. This level has the highest ceilings of all the floors, a little over 3m., as well as a wrought iron wraparound balcony, and usually had the most ornate interior. Ceiling heights are lower on the 3rd and 4th levels, and the interior detailing is simpler. The 5th floor was not intended for nobility or the wealthy, but did have balconies to visually balance the building’s exterior. The 6th floor, or attic space, was reserved for servants.

These days, since the highest floor of a Haussmann-style apartment building promises good views of the city’s rooftops, these apartments are often in high demand. Interiors of Haussmann buildings were as elegant as the exteriors. They typically featured herringbone and chevron parquet floors, elaborate plaster or wood mouldings, large rooms with tall windows, built-in wardrobes and shelves, marble fireplaces, French doors and tomette terracotta floor tiles.

Parisian life was transformed by the “vie du Boulevard” (life of the Boulevard) and “l’esprit du Boulevard”, which quickly became a characteristic aspect of Parisian life. Haussmann created a new city plan, with the large avenues bordered by buildings that were more spacious and luxurious than the previous ones.

Long avenues were constructed, such as the avenue de l’Opéra, avenue de la Grande Armée and avenue Foch. Space was freed up around monuments to make them stand out, like the Place de l’Opéra and the Place de l’Étoile (today Place Charles de Gaulle), where several avenues meet, and placed the large railway stations around the city centre. Haussmann stated his passion for the rectilinear, monumental and aesthetic, classical urban planning, with uniform buildings, places adorned with statues and broad, straight avenues leading the eye to a monument. He was influenced by his years living in Bordeaux, that had been modernised during the 17th century.

Under the Second Empire, the redevelopment of Paris also included parks such as the Bois de Boulogne and the Parc Monceau. The Prefect shifted the centre of Paris westward toward the Opera and the new boulevards, and transformed the Ile de la Cité and its surroundings to accentuate the magnificence of the city centre’s monuments and administrative buildings. He created large spaces around monuments like the Hotel de Ville, the Louvre, the Palais de Justice, and Notre Dame. The forecourt (parvis) in front of Notre Dame was created at this time.

Haussmann engineered not only grand squares and city parks, but also a comprehensive sewage system, a new aqueduct giving wide access to fresh water, a network of underground gas pipes for lighting streets and buildings, elaborate fountains, grandiloquent public lavatories and rows of newly planted trees.

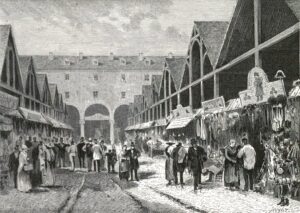

The bold new railway stations included the Gare du Nord and Gare de L’Est, the opulent Paris Opéra (known as Opéra Garnier), a number of ambitious theatres at Place du Chatelet, the giant, iron-framed Les Halles produce market (Émile Zola’s “Belly of Paris”), and the sensational network of a dozen avenues radiating from the Arc de Triomphe at Place de l’Étoile—every foreign driver’s nightmare to negotiate!

However, many contemporaries hated what Haussmann had done. Victor Hugo, sentimental for the colourful old Paris, accused Haussmann of vandalism. The renowned statesman Jules Ferry (1832-93) wrote, “We weep with our eyes full of tears for the old Paris, the Paris of Voltaire…when we see the grand and intolerable new buildings, the costly confusion, the triumphant vulgarity, the awful materialism that we are going to pass on to our descendants.” However, Haussmann’s monumental plan remains impressive, not least because he achieved so much so quickly to such a high, uniform standard. Those of us who visit Paris regularly can only attest to that, and consider ourselves fortunate to be in what many of us regard as the most beautiful city in the world.

Leave a Reply